The separation of 2,300 families after illegal border crossings has made headlines across the country. But the criminal prosecutions that led to many of those separations may be unfamiliar to most people.

In Tucson and elsewhere along the U.S.-Mexico border, the fast-track prosecution program known as Operation Streamline is essential to the Trump administration’s crackdown on illegal immigration, as it was for the Bush and Obama administrations.

An average of 12,400 people went through Streamline in Tucson in each of the past five years, court records show. And the total for the first eight months of this fiscal year was already more than 10,000.

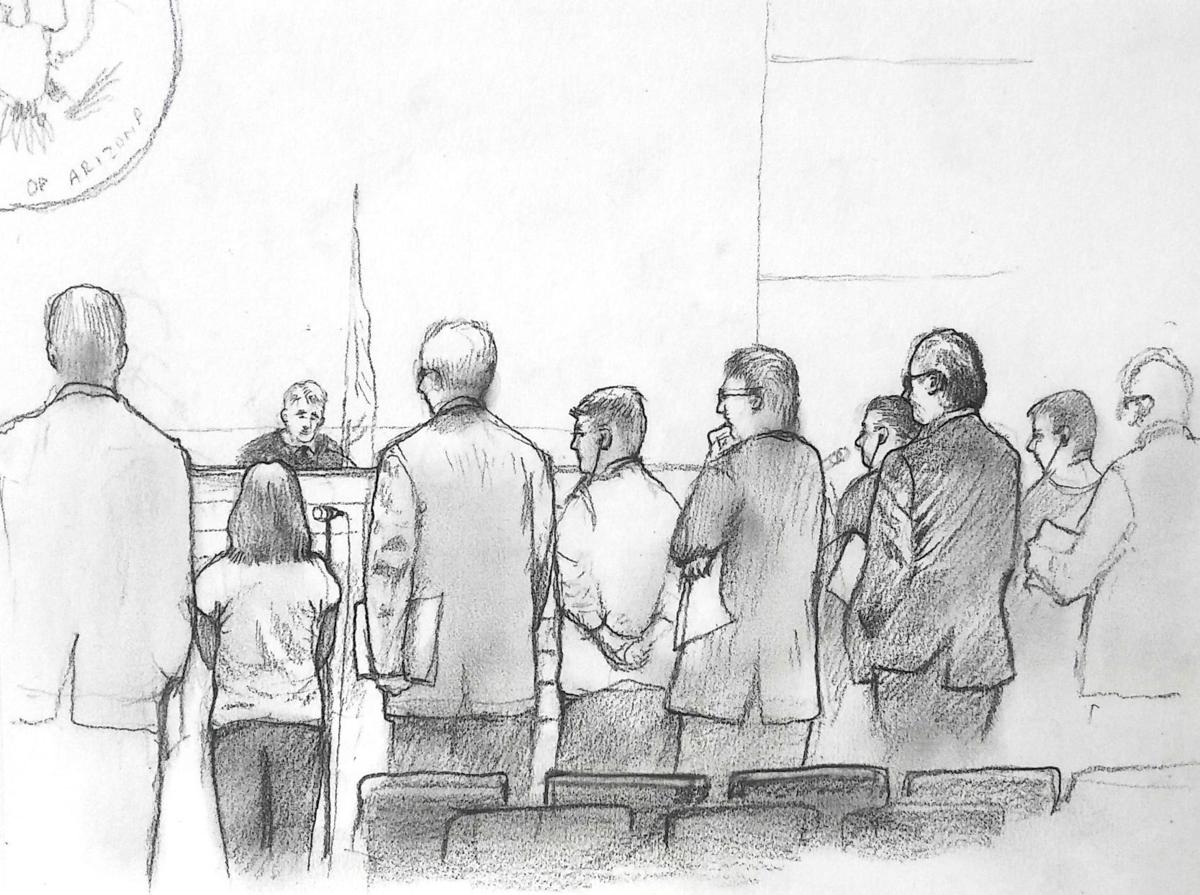

Streamline prosecutions unfold through seemingly choreographed movements by defense lawyers, prosecutors, judges, interpreters, U.S. marshals and Border Patrol agents. Those movements have been repeated most weekdays for the past decade on the second floor of the federal courthouse in downtown Tucson.

Shoulder-high stacks of court files

The start of Streamline hearings is marked by the sound of dozens of shackles being removed behind a door on the right-hand side of the courtroom.

Over the next two hours, 10 groups of seven people emerge from the door, which is guarded by at least one deputy marshal and a Border Patrol agent. A woman from the Mexican consulate usually sits in the front row by the door and chats with the agent.

The groups stand before a magistrate judge and each person pleads guilty to crossing the border illegally.

As each group is led out of the courtroom by deputy marshals, a federal prosecutor quietly removes a stack of papers from manila folders and slides them to the right side of his desk. By the end of each hearing, the stack reaches up to his shoulder.

Among the cases held in the manila folders at a recent hearing was that of a man caught crossing the border illegally near Nogales with his 16-year-old son. He told the magistrate judge they crossed the border because violent gangs in Guatemala were trying to recruit his son and had given their final warning.

The next day, a defense lawyer said his client crossed the border with her child. But they were separated by the Border Patrol hours before the hearing and she did not know where her child was.

Thousands more are sentenced to prison and exit through the door without saying anything more than “yes,” “no,” and “guilty.”

Appearance in court

The vast majority of Streamline defendants are men arrested a day or two before they appear in court. They appear before the judge in the clothes they were wearing when they were arrested, as opposed to the orange jumpsuits worn at Streamline hearings in Texas.

In Tucson, most appear wearing jeans, T-shirts and polo shirts mangled by the dayslong desert trek. Others wear Western-style button-down shirts tucked into their jeans.

Some wear soccer jerseys, including one man who sported the red-and-blue vertical stripes of Barcelona, and a Guatemalan man who wore a black-and-neon green jersey.

Others wear hunting camouflage pants and jackets, which often appear in surveillance videos and photographs of illegal border crossers in remote areas of Southern Arizona.

They wear headphones so the interpreter can explain what the judge is saying to them, although some try to respond in English. They answer the judge’s questions by speaking into microphones while their defense lawyers, who are paid by the court, stand behind them.

Language issues

Most days, a handful of people will give the wrong reply to the judge, such as answering “guilty” when the judge asks if they understand their rights. When they obviously do not understand what they are supposed to say, the judge tells their lawyer to take them aside and explain the process again.

One roadblock to communicating is the fact that some defendants speak indigenous dialects and their limited Spanish abilities raise concerns they are not understanding their rights and what is happening to them.

When the docket is full, which is most days lately, each lawyer has about five clients and meets with them between 9 a.m. and noon. They tell them the charges they face, the rights they give up by pleading guilty, and how long they will spend in prison.

At the afternoon hearing, the judge reads off a list of the rights they’re giving up and asks if they are entering their plea voluntarily.

Magistrate judges rotate weekly and each one has their own style. Some keep their comments crisp and concise, while others take great pains to repeat everything for each defendant.

On Friday, court personnel from Southern California, where Streamline will start soon, attended the Streamline hearing in Tucson. Local magistrate judges took turns presiding over groups of defendants and showing their own style.

Elsewhere in the gallery, groups of students from across the country regularly attend Streamline hearings to get a sense of how the border functions. And volunteers with the End Streamline Coalition diligently jot down case details, as they have done for years.