On Nov. 16, 1958, three Boy Scouts from Tucson vanished in a freak blizzard in the Santa Rita Mountains, triggering one of the largest and most famous searches in Southern Arizona history.

Charles “Butch” Farabee was a 16-year-old Eagle Scout when he joined the search for the three boys, one of them a classmate of his at Tucson High School. He hiked up steep draws in waist-deep snow and slept on the floor of a lodge in Madera Canyon, before being replaced by better equipped, more experienced searchers.

Farabee would go on to a career with the National Park Service, where he took part in more than a thousand other rescue operations for the missing and the injured.

Teacher Russ Cone and a bloodhound from California search for three Boy Scouts missing in the Santa Rita Mountains in 1958. The incident is included in a new book on search and rescue history in Southern Arizona.

Now the retired park ranger turned historian has documented 100 years of search and rescue work across the region.

It’s his sixth book — seventh if you count his master’s thesis — but “Southern Arizona Search and Rescue History: 1901-2000” is unlike any of his previous works. For one thing, the exhaustive, 600-page volume only exists electronically, and it’s completely free to download online.

Farabee said it’s meant to be a tribute to all search-and-rescue workers, as well as a catalog of their history in the region.

“I would like to have people understand the sacrifice that these people make,” he said, during a recent interview at the Sabino Canyon headquarters of the nonprofit, all-volunteer Southern Arizona Rescue Association, or SARA, the area’s largest and oldest search and rescue organization.

“They don’t ask for anything, not even recognition. They just go out and do it, rain or shine,” Farabee said. “I’d like the public to know that they exist.”

The book chronicles many of Tucson’s major news events from the 20th century, because search and rescue personnel were inevitably called in to help: The 1934 kidnapping of 6-year-old June Cecilia Robles, who was found alive after 19 days, shackled in a buried cage in the desert east of Tucson; an Air Force fighter jet that crashed into a Food Giant grocery store at 29th Street and Alvernon Way in 1967; deadly tornadoes a decade apart that struck near San Xavier Mission in 1964 and 1974; massive flooding from Tropical Storm Octave in the early fall of 1983 that left 13 people dead across Southern Arizona; the frantic search for 8-year-old Vicki Lynne Hoskinson after she was abducted from her Flowing Wells neighborhood and murdered in 1984.

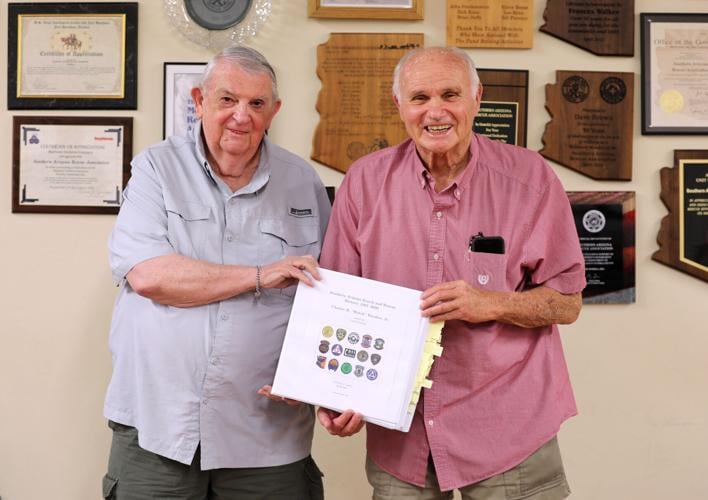

Tucson authors David Lovelock, left, and Charles “Butch” Farabee with their recent history book, “Southern Arizona Search and Rescue History: 1901-2000."

“It’s more than just search and rescue history. There is so much history of events — catastrophes, floods, tornadoes, all that jazz — that mostly is forgotten,” Farabee said. “Maybe it should be forgotten, I don’t know. But as a historian, that bothers me.”

By the numbers

The book took four years to research, write and assemble.

Farabee said he originally planned to focus only on the history of SARA, but the project quickly grew beyond that one organization.

The end result is a heavily indexed encyclopedia charting important advances in search and rescue practices and the history of individual rescue groups in the area.

Farabee also used local newspaper archives and first-person accounts to write short narratives about more than 800 rescues, tragedies and mysteries from the past century in Southern Arizona.

He collaborated on the book with renowned British theoretical physicist and retired University of Arizona professor David Lovelock, who first became involved in search and rescue through his participation as a volunteer with the REACT CB-radio emergency communication system.

In 1979, Lovelock became a supporting member of SARA, thanks to his work in radio communications and with fellow UA mathematician John Bownds, of a computer-aided, search-planning program that calculates the probability of lost subjects being found in certain areas.

Bownds initially ran the numbers on his Texas Instruments programmable calculator. Since then, Lovelock has written multiple versions of the program, first for the Commodore 64 computer, then for use on DOS and Windows operating systems. He’s also helped write numerous manuals for both the program and search and rescue operations in general.

Fire consumes the Food Giant grocery store at 29th Street and Alvernon Way on Dec. 19, 1967, after an Air Force F-4D fighter-bomber crashed into the store and nearby buildings, killing four people. The incident is included in a new book on search and rescue history in Southern Arizona.

“What the software does is to get you to estimate how well you searched the area. Then the software goes through and recalculates all the different probabilities of (the subject) being in different areas, so you can reassign (searchers) depending on where the hot area is,” said the mathematician known in the world of theoretical physics for Lovelock’s theorem and Lovelock’s theory of gravity.

Lovelock is the reason the new book is free. That was one of his conditions before he would agree to help with the project.

He has never charged any money for the software he has written to aid with search and rescue operations — something he said came to be known around the UA math department as the “Lovelock principle.” He simply refuses to “profit off of someone else’s misery,” he said.

Bownds ended up sacrificing his life for search and rescue work.

The long-time SARA volunteer died in 1993 at age 51, after a long illness possibly caused by Valley fever he contracted from dust he breathed during one of his more than 200 rescue operations.

Bownds, whose name appears in the new book some 43 times, has since been listed alongside other Southern Arizona search and rescue workers who died in the line of duty.

Also on that list is John. D. Anderson, an investigator for the Pima County Sheriff’s Department, who fell to his death while rescuing a 15-year-old boy in upper Sabino Canyon in 1948.

Anderson’s fatal fall was caught on camera by an Arizona Daily Star photographer who later became a household name in Tucson for entirely different reasons: Sam Levitz.

Search history

Mykle Raymond is also mentioned in the book dozens of times, and why not? He has participated in more than 2,500 emergency calls in the 50 years he’s been volunteering with SARA.

He also serves as archivist for Search and Rescue Council, Inc., a nonprofit corporation that coordinates the work of SARA and four other all-volunteer search and rescue groups serving Southern Arizona, none of which charge for their services.

“Search and rescue is free. A lot of people don’t know that,” Raymond said. “We insist that it be free, so that people will call sooner rather than later.”

“It’s a lot harder to get to them later,” he added.

On average, SARA responds to about two calls a week, but earlier this month, they were called out four times in a single day, which is “highly unusual,” Raymond said.

A building collapses into the raging Rillito River during deadly flooding in October 1983 that left 13 people dead across Southern Arizona. The incident is included in a new book on search and rescue history in the region.

When a call comes in, volunteers have to drop everything to respond, so they need the support of understanding spouses, children and employers, said SARA president Jason Schlueter.

Raymond seems to enjoy being sent on unscheduled hikes in the mountains at a moment’s notice. He said he regularly tells the people he is rescuing, “Thank you for inviting us out today.”

He isn’t being snide. He’s being sincere.

“The most recent time I said it was yesterday: Pulled an exhausted hiker from Chicago who got caught in the heat up on the peak, served him refreshments, walked him out and said, ‘Thank you for inviting us out today,’” Raymond said. “‘It’s a lovely day for a hike.’”

Farabee and Lovelock are already working on a second edition of the book, mostly to clean up a handful of mistakes they have found or had pointed out to them in the first edition.

Lovelock, 85, joked that he and Farabee, 80, decided not to expand the work to include the first 23 years of the current century because they were worried about living long enough to finish documenting the previous one.

You can trace the development of Southern Arizona itself through the kinds of search and rescue operations covered in the book.

In the early 1900s, most incidents involved flash floods or mine accidents. Then during World War II, searchers responded to a rash of bomber crashes throughout Southern Arizona, as servicemen trained furiously to join the fight overseas.

As Tucson grew after the war, reports of lost or injured hunters in the mountains around the city gradually gave way to missing hikers or people injured while playing in water-filled canyons in the Rincons or the Catalinas.

Farabee said Tanque Verde Falls has easily seen the most incidents — and fatalities — over the years.

SARA responds to so many calls there that the group has proactively made safety improvements to the trail leading into the canyon and installed permanent gear in the rocks above to aid in hoisting out injured people, Raymond said.

Risk and reward

Though the book mainly focuses on Pima, Cochise and Santa Cruz counties, some stories from elsewhere are included, so long as there is some connection to Southern Arizona or the rescue organizations based here.

One of the most memorable — and infuriating — incidents Farabee writes about unfolded over 12 hours in June of 1994 in a canyon known as Hell’s Hole northeast of Roosevelt Lake, where one helicopter rescue of an injured hiker turned into multiple calls to pluck rescuers from the gorge.

When it was over, a Blackhawk from Davis-Monthan Air Force Base had crashed in Hell’s Hole, badly injuring two members of its crew, and resulting in a flurry of additional, dangerous helicopter rescues.

Miraculously, no one was killed, Farabee said, but he is convinced it all could have been avoided if a few tired but otherwise healthy people had simply hiked back out of the canyon instead of calling for extraction.

“Every time that you have a helicopter involved, and every time you’ve got people going over cliffs, needlessly, it just endangers the rescuers, which basically pisses me off,” he said.

Then there was the case of the three Boy Scouts lost in the snowy Santa Ritas in 1958.

“That was my first search,” Farabee said. “In today’s climate, my parents would be arrested for child endangerment or something, because I was going out there in Levi’s and sweatshirts and stuff.”

Newspaper clippings like this one from 1967 served as source material for a new book charting 100 years of search and rescue history in Southern Arizona.

He remembers it as a “chaotic” scene, with several hundred people showing up to join the operation, including soldiers and airmen, law enforcement officers and local ranchers on horseback.

After 19 days of searching through the snow and steep terrain, the bodies of Mike Early, 15, David Greenberg, 12, and Michael La Noue, 13, were found on the south side of Josephine Saddle, in the shadow of Mount Wrightson.

In his introduction to the book, Farabee writes that search and rescue was still in its “awkward infancy” back then. In the decades since, advances in technology, training and tactics have dramatically improved the way such operations are conducted.

But despite the advent of helicopters, satellites, smartphones and drones, the core of the work is exactly what it has always been: People on the ground, who lace up their boots and march into the wilderness in search of strangers in need of help.