After jurors convicted Frank Atwood for the 1984 kidnapping and murder of 8-year-old Tucson girl Vicki Lynne Hoskinson, jury foreman Andrew Bradshaw told the Arizona Daily Star, “We made the right decision, and we’ll never doubt it.”

His mind hasn’t changed in the 35 years since.

Bradshaw’s only lingering question about the case that shook the Old Pueblo: Why hasn’t Atwood’s sentence been carried out yet?

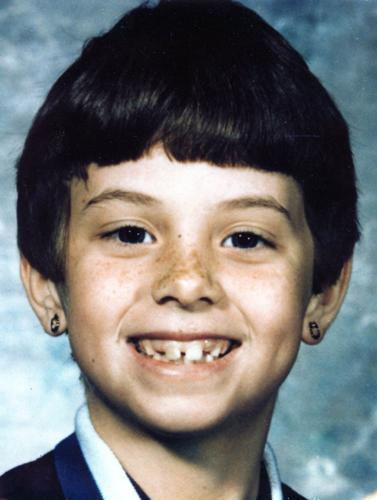

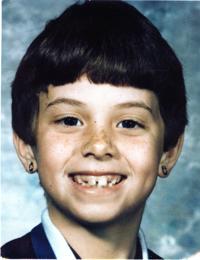

Undated photo of Vicki Lynne Hoskinson, who was murdered by Frank Jarvis Atwood in 1984.

“I’m irritated as a father that it’s taken 35 years,” said the retired construction project manager and long-time Phoenix resident. “He’s lived a little over four times as long as that little girl, and he did it on our nickel.”

Atwood was convicted on March 26, 1987, and sentenced to die six weeks later. Of the 112 inmates on Arizona’s death row, only two have been there longer than him.

Barring a last-minute stay, the 66-year-old is scheduled to die by lethal injection on June 8 at the Eyman state prison complex in Florence.

“I find no pleasure in what’s about to happen to him, because there shouldn’t be any (pleasure) in it,” Bradshaw said. “I’m just one of those who believes it should have been done 30 years ago.”

Bradshaw was working as a hospital building operations manager when he was picked to serve on the jury for the high-profile case, which was moved from Tucson to Phoenix at the request of Atwood’s attorney.

After 10 weeks of testimony, the jury spent about 11 hours over three days reviewing the largely circumstantial case before reaching its decision.

Bradshaw remembers Atwood sitting there staring at him as the verdicts were read. No single piece of evidence convinced him of Atwood’s guilt, he said. “For me, anyway, it was everything.”

Bradshaw said his opinion of the death penalty hasn’t changed over the years, either. He believed in it then, and he believes in it now.

In this case especially, he said, “It’s justified and warranted and deserved.”

During the trial in 1987, Bradshaw and his fellow jurors were under strict instructions not to read any news accounts, so he had his wife clip stories from the local papers and save them for later.

He still has a scrapbook filled with those news clippings, though he said he’s barely glanced at it in the decades since the trial.

“I don’t even know why I’ve kept it all this time, quite honestly,” he said. “Probably, on June 9th, I’m going to burn it.”

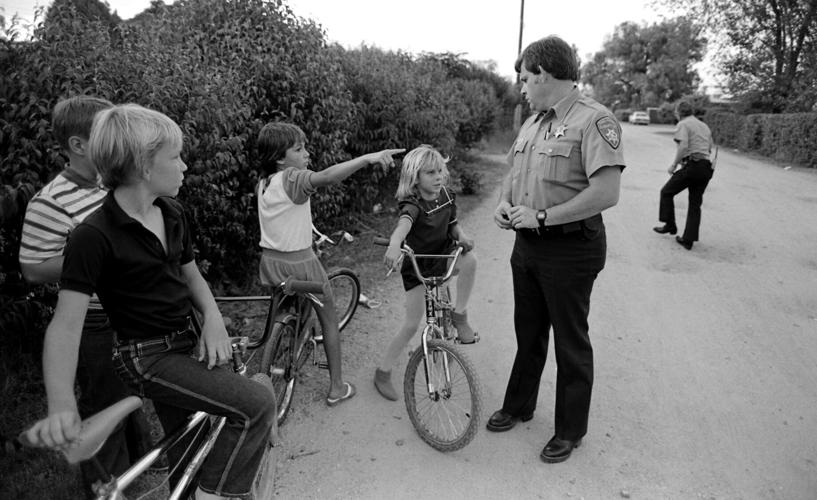

Pima County Sheriff’s deputies talk to children in the neighborhood near where Vicki Lynne Hoskinson’s bicycle was found during a search on Sept. 17, 1984, near Homer Davis Elementary School.

A frantic search

Vicki Lynne Hoskinson vanished from her Flowing Wells neighborhood on the afternoon of Sept. 17, 1984, after riding her bicycle to the Circle K at Wetmore and Romero roads to mail a birthday card to her aunt.

Her 11-year-old sister, Stephanie, found Vicki’s pink bike lying on its side in the middle of a quiet residential street less than a quarter of a mile from their home. The blue-eyed girl with short curly hair and freckles was never seen alive again.

Pima County Sheriff Chris Nanos said the crime left an indelible mark on both Tucson and the sheriff’s department.

“Vicki Lynne is a name that you don’t have to say anything else. Just Vicki Lynne, and everybody knows,” said Nanos, who was a patrol deputy at the time, still in his first year with the department.

“This was a time when our agency wasn’t as robust as it is now,” he said. “I think we grew a lot with that case.”

Chief Deputy Rick Kastigar, now the department’s second in command, was a 29-year-old public information officer with the agency in 1984.

The mailbox still stands next to a Circle K at Wetmore and Romero roads. Vicki Lynne Hoskinson disappeared after riding her bicycle to the mail box to mail a letter in 1984.

He said strangers abducting children was “very, very rare” back then — and still is today — but officers recognized almost immediately that “this was one of those rare events.”

“We didn’t have the resources we have now. We didn’t have the staffing we have now,” he said. “But we involved every element of our criminal investigations team and our patrol team looking for her.”

For weeks, Kastigar worked out of the command post investigators set up at Vicki’s school, Homer Davis Elementary, just across Romero Road from where her bike was found. He said he would get there early in the morning to be briefed by investigators, then spend the rest of the day updating the media and logging tips about the case.

The FBI and other law enforcement agencies soon joined the search as well. As many as 70 people were working out of the school at one time, Kastigar said, not counting all the newspaper and television reporters or the local residents who wandered in looking to help.

“The upswell from the community was amazing. It truly was,” he said. “People were showing up with cupcakes, coffee, well wishes, flowers (and) positive sentiments” to comfort Vicki’s dad, Ron Hoskinson; mom, Debbie Carlson; and stepdad, George Carlson, who spent many anguished hours at the command post.

Grocery stores dropped off food and drinks for the search parties. Local business owners chipped in, sometimes anonymously, to print the girl’s picture on fliers and billboards and bumper stickers that read, “Don’t forget Vicki Lynne.”

Within three days of the girl’s disappearance, tips led authorities to arrest a suspect in her kidnapping: a 28-year-old drifter in Texas named Frank Jarvis Atwood, who was staying in Tucson at the time of her abduction. Four months earlier, Atwood had been released on parole in California after serving less than four years of a five-year sentence for kidnapping and sexually assaulting an 8-year-old boy.

Meanwhile, the frantic search for Vicki continued, and so did the anxiety sweeping Southern Arizona.

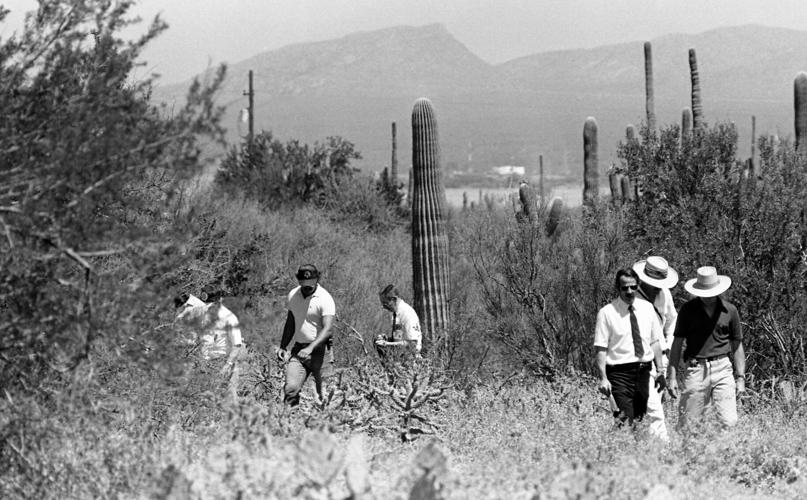

Forensic investigators from the Pima County Office of Medical Examiner and the University of Arizona survey an area where the bones of a child were found that were thought to be those of Vicki Lynne Hoskinson on April 15, 1985.

“This community was afraid. There were a lot of unknowns,” said Kastigar, who had two young daughters at home back then. “They were just slightly younger than Vicki at the time, and it scared the hell out of me.”

On April 12, 1985, seven months after she disappeared, the girl’s skeletal remains were found scattered in the desert at the west end of Ina Road. There was so little left that the medical examiner could not determine how she died or what else might have been done to her.

Atwood soon faced one count of first-degree murder along with the kidnapping charge.

Though none of Vicki’s blood, fingerprints or hair was ever found inside of his car, forensic experts identified pink paint from her bicycle and a scrape from one of her pedals on the vehicle. Traces of nickel recovered from the bike were matched to the car’s bumper.

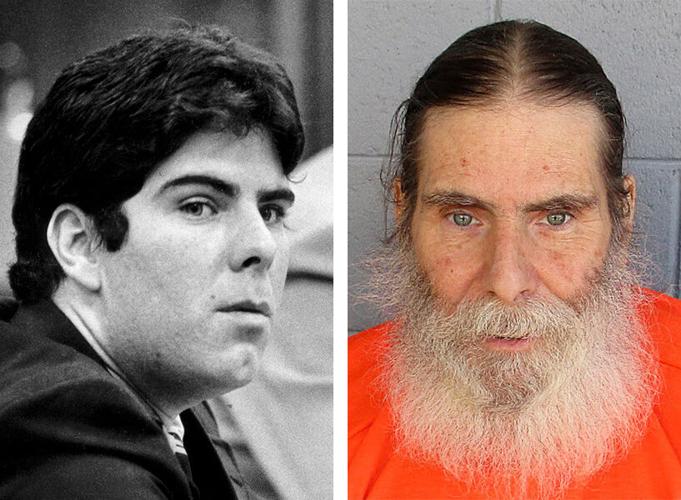

Frank Jarvis Atwood at his arraignment in 1985, left, and recently at the Arizona State Prison.

Authorities also had testimony from Atwood’s acquaintances, who saw him with blood on his clothes the afternoon of the abduction, and from a coach at Vicki’s school, who noticed a suspicious vehicle in a nearby alley that day and took down the license plate number for what turned out to be Atwood’s car.

All these years later, the case still stirs an emotional response in Kastigar — especially when he thinks about that innocent little girl, happily pedaling around her neighborhood with no understanding of “how vile and evil humans can be to other humans,” he said. “It’s just so sad to think of what likely happened to her.”

He expects Atwood’s death to bring some measure of comfort not just to Vicki’s family, but to those who were involved in searching for her and her killer, himself included.

“It’s a circumstantial case, but it’s very, very clear to me,” Kastigar said. “There’s no doubt in my mind that we arrested the right guy, and that he is sitting awaiting his fate.”

Change of heart

Until about a month ago, George and Debbie Carlson were planning to skip Atwood’s execution.

Now Vicki’s parents are determined to be there to see things through, with emotional support from a number of their family members.

“We just changed our minds two or three weeks ago,” Debbie said Thursday from their home on the east side of Tucson. “Deep down, we wanted to see that final justice for Vicki, to be her representation there as her parents. I think that’s what it finally came down to.”

They were warned to expect a flurry of late filings and rushed court proceedings in the days leading up to the execution, as Atwood, his legal team and his supporters fight to keep him alive. That’s exactly what has happened so far.

On May 24, the Carlsons traveled to the state prison in Florence to help convince the Arizona Board of Executive Clemency to deny Atwood’s request to be spared. Then on Friday, they headed to Phoenix for a hearing on a petition arguing against the execution procedure on grounds that it violates the Americans with Disabilities Act. A judge has not yet ruled on Friday’s effort.

They were still trying to decide whether to return to Phoenix on Monday for another hearing, this one challenging the clemency board’s decision based on how it conducted its meeting last month.

“Anything that’s going before a judge, we’re going, because I think it gives them a reminder that we’re still here and we’re still fighting for Vicki,” Debbie Carlson said.

Debbie Carlson collapses in grief over the casket with the body of her daughter, Vicki Lynne Hoskinson, during graveside services on May 30, 1985, at Evergreen Cemetery.

It’s been a long fight.

The distraught young couple that appeared on the front page of the Star on Sept. 20, 1984, holding their missing daughter’s Cabbage Patch Kid, has now been married for 42 years. They have six grandchildren ranging in age from 6 to 21 — blessings delivered to them by Vicki’s two older sisters and younger brother.

Some of George and Debbie’s oldest friends are people they met while searching for their daughter, including several local detectives, the FBI agent who was assigned to their case and their advisor from the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children.

At the Carlsons’ home, a piece of polished wood hangs above their dining room table beneath Debbie’s favorite Bible verse: “With God, all things are possible.” The wood was salvaged from a palo verde tree that was planted in Vicki’s honor at Homer Davis Elementary School in 1985 and grew for 30 years before it was blown down in a thunderstorm.

A lot has happened to Atwood in the past 35 years, too, despite his incarceration.

He got married in 1991 to a woman he began corresponding with shortly after his conviction. He has since been baptized in the Greek Orthodox Christian church and completed enough correspondence courses for two associate’s degrees, a bachelor’s degree and a master’s degree in literature. He even has his own website where he sells the books he has written behind bars on religion, criminal justice and his case.

A large group of supporters from Atwood’s church appeared at his clemency hearing, where he maintained his innocence but said he hoped his execution would bring peace to Vicki’s family.

The Carlsons just want it to be over.

“Enough’s enough,” Debbie Carlson said. “I’m 67 years old. George is 70. We’ve spent over half of our lives fighting for justice for Vicki.”

“We don’t know what normal is anymore,” George Carlson added. “I think we’re excited to experience that again. To be able to wake up in the morning and not have that cloud over you. Is the AG’s office going to call? Did he file another motion? Is there going to be another delay? We haven’t had that in 38 years.”

To them, Atwood’s death is a chance for a new life.

“I don’t like the word closure, because it’s never closed. We will never have closure, because we won’t have Vicki,” Debbie Carlson said. “But it will be a new beginning. We can close that chapter out, and we can start anew. That’s what we’re looking forward to.”

Photos: The search for Vicki Lynne Hoskinson in 1984-85

Vicki Lynne Hoskinson

Updated

Pima County Sheriff's deputies talk to children in the neighborhood near where Vicki Lynne's bicycle was found during the search for Vicki Lynne Hoskinson on Sept. 17, 1984 near Homer Davis Elementary School on Romero Road, Tucson.

Vicki Lynne Hoskinson

Updated

Pima County Sheriff's Det. Gary Dhaemers talks with neighborhood resident Vickie Marshall during the search for Vicki Lynne Hoskinson on Sept. 18, 1984 near Homer Davis Elementary School on Romero Road, Tucson.

Vicki Lynne Hoskinson

Updated

Undated photo of Vicki Lynne Hoskinson, who was murdered by Frank Jarvis Atwood in 1984.

Vicki Lynne Hoskinson

Updated

Pima County Sheriff's deputies check for physical evidence during the search for Vicki Lynne Hoskinson on Sept. 17, 1984 near Homer Davis Elementary School on Romero Road, Tucson.

Vicki Lynne Hoskinson

Updated

A Pima County Sheriff's deputy talks to a neighborhood boy during the search for Vicki Lynne Hoskinson on Sept. 17, 1984 near Homer Davis Elementary School on Romero Road, Tucson.

Vicki Lynne Hoskinson

Updated

during the search for Vicki Lynne Hoskinson on Sept. 18, 1984 near Homer Davis Elementary School on Romero Road, Tucson.

Vicki Lynne Hoskinson

Updated

Volunteers coordinate their search for Vicki Lynne Hoskinson on Sept. 18, 1984 near Homer Davis Elementary School on Romero Road, Tucson.

Vicki Lynne Hoskinson

Updated

Pima County Sheriff's detectives coordinate their search for Vicki Lynne Hoskinson on Sept. 18, 1984 near Homer Davis Elementary School on Romero Road, Tucson.

Vicki Lynne Hoskinson

Updated

Law enforcement officers during the search for Vicki Lynne Hoskinson, 8, in Tucson in 1984.

Vicki Lynne Hoskinson

Updated

A billboard for missing girl Vicki Lynne Hoskinson in Tucson in 1984.

Vicki Lynne Hoskinson

Updated

Pima County Sheriff Clarence Dupnik, left, speaking at during a press conference on Sept. 20, 1984, to announce the arrest of two men in connection with the abduction of Vicki Lynn Hoskinson. Others pictured: County Attorney Steve Neely and FBI agents Dick Swinson and Richard Rogers.

Vicki Lynne Hoskinson

Updated

Arraignment of Frank Jarvis Atwood in 1985. He was charged with first-degree murder in connection with the death of Vicki Lynne Hoskinson.

Vicki Lynne Hoskinson

Updated

Thelma Hoskinson, right, grandmother of Vicki Lynn Hoskinson, cries during a press conference on Sept. 20, 1984, announcing the arrest of two men in connection with Vicki Lynne's abduction and death.

Vicki Lynne Hoskinson

Updated

Forensic investigators from the PIma County Office of Medical Examiner and the University of Arizona survey an area where the bones of a child were found that were thought to be those of Vicki Lynne Hoskinson on April 15, 1985

Vicki Lynne Hoskinson

Updated

Forensic investigators from the PIma County Office of Medical Examiner and the University of Arizona survey an area where the bones of a child were found that were thought to be those of Vicki Lynne Hoskinson on April 15, 1985

Vicki Lynne Hoskinson

Updated

The Arizona Department of Public Safety helicopter hovers during the search for Vicki Lynne Hoskinson on April 12, 1985 at the end of Ina Road, west of Interstate 10.

Vicki Lynne Hoskinson

Updated

Members of Southern Arizona Rescue Association and Pima County Sheriff's deputies coordinate search during for Vicki Lynne Hoskinson on April 12, 1985 at the end of Ina Road, west of Interstate 10.

Vicki Lynne Hoskinson

Updated

A member of the Pima County Sheriff's Posse on horseback rides west on Ina Road during the search for Vicki Lynne Hoskinson on April 12, 1985 at the end of Ina Road, west of Interstate 10.

Vicki Lynne Hoskinson

Updated

Children cry as the casket of Vicki Lynne Hoskinson is carried during graveside services on May 30, 1985 at Evergreen Cemetery in Tucson.

Vicki Lynne Hoskinson

Updated

Debbie Carlson collapses in grief over the casket with the body of her daughter, Vicki Lynne Hoskinson, during graveside services on May 30, 1985 at Evergreen Cemetery in Tucson.