FLORENCE — After spending more than half of his life on death row, Frank Jarvis Atwood was executed Wednesday for the 1984 abduction and murder of an 8-year-old Tucson girl.

The 66-year-old with a long white beard was pronounced dead at 10:16 a.m., 12 minutes after he was injected with a fatal dose of the sedative pentobarbital at the state prison in Florence.

Atwood was calm and polite throughout the process, suggesting to medical personnel at one point that they place the needle in his hand after they struggled to tap a vein in his right arm.

He used his last words to thank God, his priest, his wife and his legal team but took no responsibility for the crime.

“I pray the Lord will have mercy on all of us and that the Lord will have mercy on me,” he said just before the drug was administered.

Atwood was convicted in 1987 of kidnapping and killing third grader Vicki Lynne Hoskinson, who disappeared from her Flowing Wells neighborhood on Sept. 17, 1984, while she was out riding her bicycle after school.

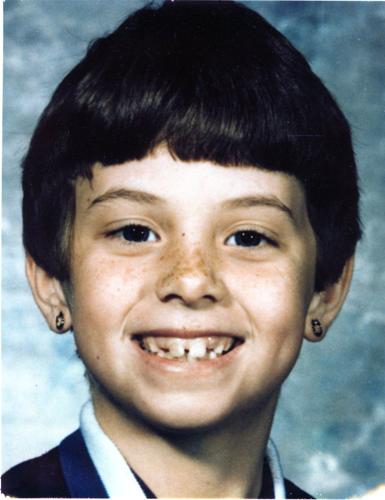

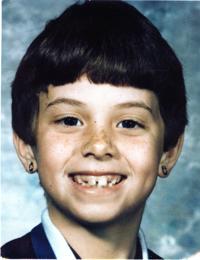

Hoskinson

Her skeletal remains were found seven months later scattered in the desert at the west end of Ina Road.

About 40 people — including Vicki’s mother and stepfather, Debbie and George Carlson, and several other family members — crowded into a cramped observation room to witness the execution through a window and on three closed-circuit television screens.

Also on hand were law enforcement officials involved in the case, including Arizona Attorney General Mark Brnovich, and three witnesses from Tucson media outlets, including the Arizona Daily Star.

Several supporters were there on Atwood’s behalf, among them members of his legal team and the Greek Orthodox Christian church he joined during his 35 years on death row.

The only sound in the observation room came from Atwood’s wife, Rachel, who sniffed and cried throughout the procedure.

She began writing letters to Atwood shortly after his conviction, and the two were married in 1991. They wrote and published a book together in 2018 called “And the Two Shall Become One,” about their relationship and their religious beliefs.

Dressed in an orange prison jumpsuit and a black cleric’s hat with a red cross on it, Atwood looked over at his wife and smiled several times before the pentobarbital caused him to slip into unconsciousness, snore briefly and then stop breathing.

He was joined in the execution chamber by Father Paisios, the head of St. Anthony’s Greek Orthodox Monastery in Florence, who draped his embroidered red stole over the condemned man’s forehead and held it there with a religious medallion throughout the process.

As part of his last words, Atwood thanked the priest for shepherding him “to the very edge of paradise.”

He did not address Vicki’s family or look in their direction, and his only reference to the case was to call it a “horrible judicial unfairness that led me to my salvation.”

Debbie Carlson, mother of murdered 8-year-old Vicki Lynne Hoskinson, pauses while speaking about her daughter at a news conference after Frank Atwood was put to death by lethal injection at the Arizona State Prison Complex in Florence.

Final appeal

The U.S. Supreme Court cleared the way for Atwood’s execution Wednesday morning after rejecting a final appeal by his lawyers.

He was the second death row inmate to die by lethal injection since the state resumed its use of capital punishment last month after a pause lasting almost eight years.

On May 11, Clarence Dixon was put to death for the 1978 murder of 21-year-old Arizona State University student Deana Bowdoin.

Arizona’s last execution before that came on July 23, 2014, when convicted double-murderer Joseph Wood took almost two hours to die after being given 15 doses of a two-drug combination the state no longer uses.

That execution was supposed to be over in 10 minutes but dragged on so long that the Arizona Supreme Court convened an emergency hearing to decide whether to halt the procedure.

Atwood was given the choice of dying in Arizona’s gas chamber, which was refurbished in 2020. Lethal injection was selected for him by the state when he did not choose between the two available options.

Arizona is the only state with a working gas chamber and the last state to use one for an execution in the United States in more than two decades.

At the time of Vicki’s disappearance in 1984, Atwood was on parole after serving less than four years of a five-year sentence in California for the kidnapping and sexual assault of an 8-year-old boy.

He was arrested in Texas on Sept. 20, 1984, based on tips to authorities from his own father and from a coach at Vicki’s elementary school who saw someone suspicious near the campus the day the girl was taken and took down the man’s license plate number.

Atwood would spend the last 37 years of his life behind bars, nearly all of it in Florence, about 70 miles northwest of Tucson, where he was baptized into the Greek Orthodox Church, earned several college degrees and wrote several books on religion, criminal justice and his case.

He was the 12th-oldest among the 109 men and three women currently facing death sentences in Arizona. Only two current inmates have been on death row longer than Atwood was, according to Judy Keane, spokeswoman for the Arizona Department of Corrections, Rehabilitation and Reentry.

Remembering Vicki

Because of back pain that his legal team tried to use as a basis to delay the execution, Atwood was provided with a wedge-shaped pillow to prop up his neck as he was strapped to the black, padded restraint table by a team of corrections officers wearing masks and sunglasses to conceal their identities.

He sighed several times during the roughly 30 minutes of preparation time, but he showed no outward signs of discomfort, even when the IV needles were inserted into his left arm and right hand.

He thanked the medical personnel several times as they prepared him to die.

During a press conference at the prison following the execution, crime victims’ advocate Colleen Clase criticized how long it took for Atwood’s sentence to be carried out, noting “at least 90 events that triggered delays” over the past 35 years.

“For decades, it would be fair to say that the criminal justice system failed Vicki’s family,” said Clase, chief counsel and CEO of Arizona Voice for Crime Victims. “That changed today, but without an apology to Vicki’s family and without any semblance of remorse or responsibility.”

In an interview last week, Debbie Carlson described Atwood as Tucson’s embodiment of the boogeyman. On Wednesday, she didn’t refer to him at all.

Instead, she spent her time at the podium talking about Vicki.

Flanked by pictures of the girl, Carlson described her daughter’s infectious laugh, heart-melting smile and feisty personality that earned her the loving nickname of “Dennis the Menace.”

“I always had to dress Vicki last when we were getting ready to go somewhere, because she would always manage to find a mud puddle, a dirt pile, a water hose or something to get herself dirty,” Carlson said.

She addressed her daughter directly at the end of her remarks, turning her gaze to the ceiling with tears in her eyes.

“Vicki, I want you to be free, little one,” she said. “Until we meet again, we will miss you, and we will always love you.”

Photos: The search for Vicki Lynne Hoskinson in 1984-85

Vicki Lynne Hoskinson

Updated

Pima County Sheriff's deputies talk to children in the neighborhood near where Vicki Lynne's bicycle was found during the search for Vicki Lynne Hoskinson on Sept. 17, 1984 near Homer Davis Elementary School on Romero Road, Tucson.

Vicki Lynne Hoskinson

Updated

Pima County Sheriff's Det. Gary Dhaemers talks with neighborhood resident Vickie Marshall during the search for Vicki Lynne Hoskinson on Sept. 18, 1984 near Homer Davis Elementary School on Romero Road, Tucson.

Vicki Lynne Hoskinson

Updated

Undated photo of Vicki Lynne Hoskinson, who was murdered by Frank Jarvis Atwood in 1984.

Vicki Lynne Hoskinson

Updated

Pima County Sheriff's deputies check for physical evidence during the search for Vicki Lynne Hoskinson on Sept. 17, 1984 near Homer Davis Elementary School on Romero Road, Tucson.

Vicki Lynne Hoskinson

Updated

A Pima County Sheriff's deputy talks to a neighborhood boy during the search for Vicki Lynne Hoskinson on Sept. 17, 1984 near Homer Davis Elementary School on Romero Road, Tucson.

Vicki Lynne Hoskinson

Updated

during the search for Vicki Lynne Hoskinson on Sept. 18, 1984 near Homer Davis Elementary School on Romero Road, Tucson.

Vicki Lynne Hoskinson

Updated

Volunteers coordinate their search for Vicki Lynne Hoskinson on Sept. 18, 1984 near Homer Davis Elementary School on Romero Road, Tucson.

Vicki Lynne Hoskinson

Updated

Pima County Sheriff's detectives coordinate their search for Vicki Lynne Hoskinson on Sept. 18, 1984 near Homer Davis Elementary School on Romero Road, Tucson.

Vicki Lynne Hoskinson

Updated

Law enforcement officers during the search for Vicki Lynne Hoskinson, 8, in Tucson in 1984.

Vicki Lynne Hoskinson

Updated

A billboard for missing girl Vicki Lynne Hoskinson in Tucson in 1984.

Vicki Lynne Hoskinson

Updated

Pima County Sheriff Clarence Dupnik, left, speaking at during a press conference on Sept. 20, 1984, to announce the arrest of two men in connection with the abduction of Vicki Lynn Hoskinson. Others pictured: County Attorney Steve Neely and FBI agents Dick Swinson and Richard Rogers.

Vicki Lynne Hoskinson

Updated

Arraignment of Frank Jarvis Atwood in 1985. He was charged with first-degree murder in connection with the death of Vicki Lynne Hoskinson.

Vicki Lynne Hoskinson

Updated

Thelma Hoskinson, right, grandmother of Vicki Lynn Hoskinson, cries during a press conference on Sept. 20, 1984, announcing the arrest of two men in connection with Vicki Lynne's abduction and death.

Vicki Lynne Hoskinson

Updated

Forensic investigators from the PIma County Office of Medical Examiner and the University of Arizona survey an area where the bones of a child were found that were thought to be those of Vicki Lynne Hoskinson on April 15, 1985

Vicki Lynne Hoskinson

Updated

Forensic investigators from the PIma County Office of Medical Examiner and the University of Arizona survey an area where the bones of a child were found that were thought to be those of Vicki Lynne Hoskinson on April 15, 1985

Vicki Lynne Hoskinson

Updated

The Arizona Department of Public Safety helicopter hovers during the search for Vicki Lynne Hoskinson on April 12, 1985 at the end of Ina Road, west of Interstate 10.

Vicki Lynne Hoskinson

Updated

Members of Southern Arizona Rescue Association and Pima County Sheriff's deputies coordinate search during for Vicki Lynne Hoskinson on April 12, 1985 at the end of Ina Road, west of Interstate 10.

Vicki Lynne Hoskinson

Updated

A member of the Pima County Sheriff's Posse on horseback rides west on Ina Road during the search for Vicki Lynne Hoskinson on April 12, 1985 at the end of Ina Road, west of Interstate 10.

Vicki Lynne Hoskinson

Updated

Children cry as the casket of Vicki Lynne Hoskinson is carried during graveside services on May 30, 1985 at Evergreen Cemetery in Tucson.

Vicki Lynne Hoskinson

Updated

Debbie Carlson collapses in grief over the casket with the body of her daughter, Vicki Lynne Hoskinson, during graveside services on May 30, 1985 at Evergreen Cemetery in Tucson.