About 30 miles south of Tucson is Helvetia Road, which begins west of the Santa Rita Mountains and runs through the mountain range to its eastern side. In the area are also Helvetia Spring and Helvetia Lookout.

The names of all three derive from an old mining camp and mining district formed in the late 1800s.

The Santa Ritas south of Tucson have been a mining locale since at least the days when present-day Southern Arizona was part of the Spanish Empire, on through the years following the Gadsden Purchase of 1854 when the land became a part of the United States.

It was always for silver or gold, not copper. That changed in 1875 when Tucson businessmen Pinckney R. Tully and Estevan Ochoa —who were involved in freighting and mining — hauled about 5,000 pounds of copper ore to Tucson to be smelted before taking the bar copper to the store of Wm. B. Hooper & Co. in Yuma.

In 1878, Ben Hefti, T.G. Roddick and several other claimholders in the range formed the Helvetia Mining District. Hefti named it after the ancient name of his birthplace, Switzerland. This district was on the western slope of the mountains and encompassed an area 10 miles square.

The following year, Roddick and James K. Brown, co-owners of the nearby Sahuarito Ranch, filed a mining claim known as the Modoc, possibly the first one since the new district was formed, to go along with the previous claims in the Santa Ritas before the district was officially formed.

In 1883, with a national recession in effect, copper prices fell so low that it was not beneficial to mine the copper in the district, so not much of this mineral was exploited in the Helvetia Mining District.

After a long period, a revival took place in the early 1890s, as demand increased for copper wire for new electrical products, driven by the country’s fascination with electricity.

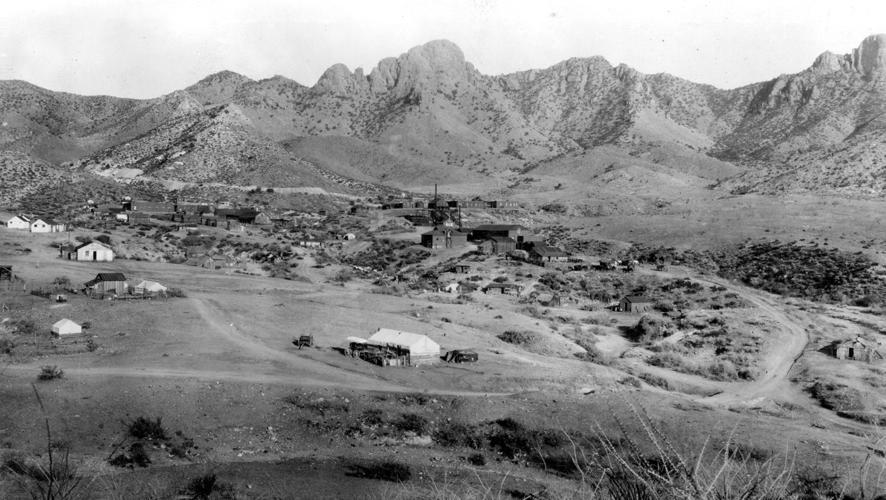

Helvetia as it appeared in 1909 with the smelter as the centerpiece, and a railroad bend.

Paine Webber & Co., an eastern investment firm, began operating in the Helvetia Mining District at this time, and in the early stages did a lot of testing of its property to ascertain its potential value. Numerous shafts were dug, and exploratory drillings were made.

During this assessment period, a crew of laborers was hired, which formed the origins of what would later become the Helvetia mining camp.

This fledgling camp was on the western slope of the range. Vail Station (now the community of Vail) was just 17 miles away, and Tucson was about 30 miles distant.

By May 1898, the camp had grown to include several permanent company buildings, an eating house for company employees, several stores, a row of tents for workers and four saloons.

By 1899, Paine Webber & Co. had established the Helvetia Copper Co. of New Jersey as a separate entity to handle its mining in the Helvetia district.

Changes also took place in the mining camp itself, most notably a population explosion. Before April 1899, there were less than 55 men employed by the mining company at the site, but by December of that year the camp had 350 company workers and a total population of about 550.

The first stage line from Tucson to the camp was established, which ran three times a week. A wagon road to Vail Station, a railhead on the Southern Pacific, had already been completed to haul heavy mining equipment and also passengers by stage line.

That year also saw the installation of a large smelter in the mining town and crews constructed roads to the different mines, scattered throughout the area, to connect them to the new smelting plant. A narrow-gauge railroad, eventually reaching more than 4 miles in length, was completed, which transported ore from the mines farther away from Helvetia.

Merchants such as Verdugo and Barcelo set up shop. Camp butchers Casky and Korb sold cuts of beef to miners that had been sold to them by ranchers in the area. There was also a shoemaker, a barbershop and a Chinese laundry.

The miners who worked inside the mine, known as “underground men,” could make up to $3 per day, while the ones who worked aboveground, in safer conditions, known as “surface men,” might earn up to $1.50 a day.

As researcher Avi Buckles wrote, “ … This would lead to the development of Helvetia into Pima County’s biggest and most important mining camp around the turn of the twentieth century, a title that it would hold for a few brief years.”

As the new century dawned on the camp, the company began to benefit from several rich copper deposits they had located. Residents attempted to make their new home a more civilized place, by requesting from the county educational facilities for their children, which occurred that year with the opening of Helvetia’s first school. The camp also got a post office.

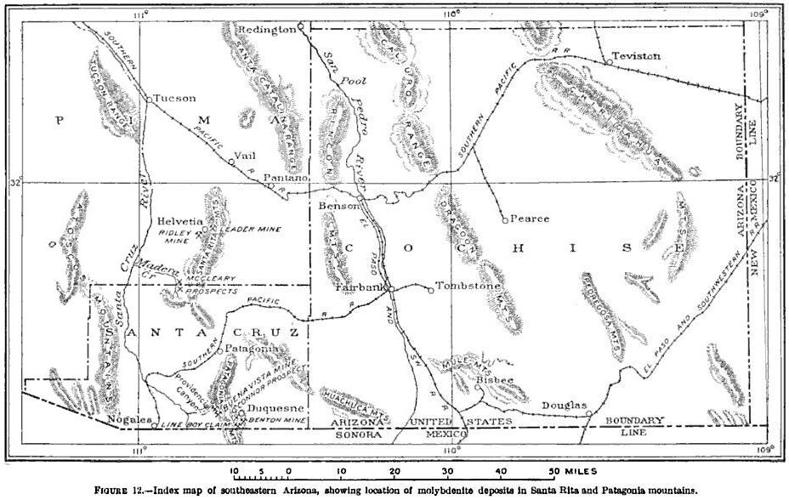

Circa 1910 U.S. Geological Survey map of Southeastern Arizona including Helvetia.

While things appeared to be improving in the small town, the Helvetia Copper Co., despite all the raw copper ore in the area, realized the potential limitations on profitability when the smelter had to shut down due to lack of water and at other times due to lack of coke (a concentrated form of bituminous coal) that was carried by freight wagon from the Vail Station to keep the fires burning.

To make things worse, late in the year, the smelter caught fire and was completely destroyed. The result was the laying off of half the company’s workforce.

By the following year, 1901, the smelting plant had been reconstructed, and operations were once again in full swing.

The good times wouldn’t last, though. In 1902, an industrial recession took hold of the country, causing a steady decline in copper prices. The devaluation of this malleable metal caused the Helvetia Copper Co. to temporarily shut down all operations in the mining area.

Things started to look up the following year when the Michigan and Arizona Development Co. purchased a large amount of stock in the old Helvetia Copper Co. of New Jersey and began working some of the mines. In the fall of 1905, it was reorganized under a new name, the Helvetia Copper Co. of Arizona.

In 1906, the furnace of the smelting plant at Helvetia was repaired, and a dynamo was added to generate electricity which powered it. The smelting of ores resumed. The electrical generator also lit up most houses in the mining camp, possibly the first time the camp was lighted at night.

The smelting likely lasted about a year before the plant broke down again, and from then on, ore was hauled by a 12-horse team, pulling heavy freight wagons with wide metal wheels, to Vail Station.

The Panic of 1907, a national financial crisis, struck the mining company and camp hard, and the Helvetia Copper Company was forced to shut down most operations late in the year.

Production at the mining camp increased the following year, and the Consolidated Telephone Co. ran a telephone line from Vail to Helvetia, allowing the mining company and residents a much quicker way to communicate with the outside world.

In 1910, Oscar Buckalew, a one-legged pioneer and former clerk to the U.S. District Court in Tucson who ran a stock ranch connected with his store in the mining camp, was shot through the head at his ranch home outside of Helvetia.

Despite a long investigation and public anger, the assassin was never caught, and the killing served as a reminder to residents of the dangers of living far from the reach of law enforcement. It also kept the fading mining camp in the news, at least for a short while.

In 1911, the mining company shut down operations in the Helvetia Mining District. The camp would survive for a few more years, being revived for a short period during World War I, when copper was needed for the war effort.

But after that, the vast majority of residents left for Tucson or the Greaterville mining camp in 1923.

This is the third of our history quizzes. How much do you know?