Herman Ehrenberg was born in Prussia, but his exploits as a transplant to America in the 1800s included fighting in the Texas Revolution, traveling the Oregon Trail, taking part in the California Gold Rush and mapping the Gadsden Purchase, among other brushes with iconic history.

After his 1816 birth in Steuden, Prussia (now part of Germany), he got a liberal education and worked as a teenager in a commercial enterprise, but it was not for him. A rolling stone, he took off for adventures.

Ehrenberg arrived in New York City in 1834 and then moved on to New Orleans. When the Texas Revolution began in 1835, he signed on as a volunteer with the New Orleans Greys.

He served in the Battle of Coleto in 1836, where he was forced to surrender by Mexican soldiers along with the rest of Col. James W. Fannins’ command. He was one of a small percentage of prisoners who survived Mexican General Antonio López de Santa Anna’s ordered Goliad Massacre at Goliad, Texas.

He became a citizen of the Republic of Texas but after contracting an illness in 1840, returned to Europe for medical treatment. He spent 1842-43 in Halle, Prussia, teaching English and writing his memoirs, Texas and Its Revolution. He may have also studied civil engineering.

In the summer of 1843, he returned to the U.S., arriving in New Orleans, then moving on to St. Louis. The following year, he joined a fur trapping outfit departing to the Pacific Coast via the Oregon Trail.

From here, he crossed the Pacific Ocean to Hawaii in 1845, where the government paid him to survey streets and draw a map of Honolulu.

By June 1847, he was in present-day La Paz, Baja California Sur, Mexico, at that point occupied by American military forces due to the Mexican-American War (1846-1848), where he was involved in mercantile pursuits. When the American soldiers left La Paz for California, he went with them. He also took part in the California Gold Rush in 1848-49.

By 1853, he was in San Francisco, and it was here he first met another restless soul, Charles D. Poston, who worked at a monotonous desk job. Poston had become aware that U.S. President Franklin Pierce wanted to obtain more land from Mexico in order to bring about a southern railroad route to the Pacific Ocean. He formed ambitious plans — that included Ehrenberg and other adventurers — to profit from Pierce’s land purchase, which came to be known as the Gadsden Purchase.

Poston wrote, “In … 1854, Mr. Ehrenberg joined the writer for a reconnaissance of then recently acquired territory, which is now called Arizona; and, with a party of 25 men, examined the country of Sonora, from the mouth of the Gulf of California to the Gila River, stopping at the towns of Fuerte, Alamos, Guaymas, Hermosillo, Ures, San Miguel and Altar, passing through the Papagueria (Tohono O’odham land), where the 4th of July, 1854, was celebrated by the Americans on their own soil, at Sans-Saida villages, by copious libations of mescal accompanied by a feast of pitayahs (organ pipe cactus fruit) and milk, much to the delight of the … chief, whose name was Tomas.”

They then headed to the junction of the Gila and Colorado rivers, across from Fort Yuma, California. Here, Ehrenberg copied Major Samuel Heintzelman’s (the builder and commander of Fort Yuma) survey of Fort Yuma and then made a survey for the proposed townsite of Colorado City (now Yuma, Arizona), although not much happened here for many years.

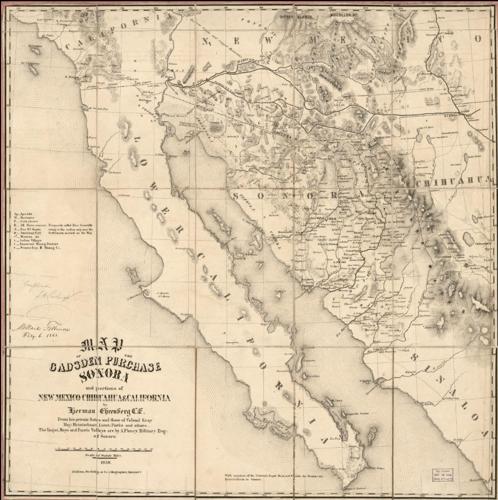

Then it was back to San Francisco where Ehrenberg turned in his manuscript map, which was published as the 1854 “Map of the Gadsden Purchase, Sonora and portions of New Mexico, Chihuauhua & California.” It was the first map of the newly acquired land that became southern Arizona.

1858 revised Map of the Gadsden Purchase by Herman Ehrenberg.

Meanwhile, Poston took mineral specimens, maps and information and headed back east to places like Philadelphia, New York City and Cincinnati. At the latter city Heintzelman joined him and helped to get investors to form the Sonora Exploring & Mining Company.

In August 1856, Ehrenberg, now back in the Gadsden Purchase — which by this time was part of Dona Ana County, New Mexico Territory — met Poston at Tucson. They set up the company headquarters at Tubac, the former Mexican fort.

In 1858, Ehrenberg resigned from the enterprise, however, because he stated that Poston was continually exaggerating the value of their mines.

The same year saw Ehrenberg’s magnum opus, the new 1858 “Map of the Gadsden Purchase, Sonora and portions of New Mexico, Chihuahua & California,” published. The San Francisco Daily Alta California newspaper shared with its readers:

“Besides a clear representation of the topography of Sonora and Gadsden Purchase, a very important matter by the way in a mountainous country, the map gives also the localities of the mining districts, the gold placers, the Indian villages...”

He kept estimated numbers of the Native American groups in the Gadsden Purchase. For example, in 1859, he shared with The Weekly Arizonian newspaper, “The Papago Indians (Tohono O’odham) inhabit the western portion of Arizona and the northwest region of Sonora. Their number is about 4,000, of which 1,000 live in Quitovaca, Caborca and other portions of northern Sonora.”

When the U.S. Civil War broke out, in 1861, Union soldiers were sent back East and the Apaches went on a rampage that led Ehrenberg and Poston to relocate to San Francisco.

By 1863, though Union troops had returned, Ehrenberg and Poston were residing at the boomtown of La Paz on the Colorado River, about 110 miles north of Fort Yuma, where gold strikes had occurred. Here Ehrenberg befriended Michael Goldwater, a prominent merchant in town.

He surveyed a road from La Paz to another town called Weaver, which the Arizona Miner newspaper named Ehrenberg Road, and surveyed a town site about six miles south of La Paz called Mineral City.

In 1864, Ehrenberg visited San Francisco on two occasions, and it’s likely he got hold of a copy of “Bancroft’s Hand-Book Almanac for the Pacific States … For The Year 1864” (although it was written in 1863).

This reference book shared some information about the new Arizona Territory:

“The Territory of Arizona was created by (an) Act of Congress approved Feb. 24, 1863. ... The southern portion of Arizona formed part of the territory purchased from Mexico in 1854, heretofore known as the ‘Gadsden Purchase.’ The temporary capital (in 1863) is Tucson, situated near the center of the southern portion of the (Arizona) Territory.”

It listed only two towns in the Arizona Territory: “Tucson — Territorial Capital — No post office; 280 miles east of Fort Yuma” and “La Paz — No Post Office; located on the east bank of the Colorado River. Population about 1,500. It is the principal town in the (Arizona) Territory and will probably be selected for the future capital.”

As it turned out, a new town, Prescott, became the first permanent capital. Ehrenberg’s initial visit to Prescott was in mid-1864 and in January 1866, he became a director of the original Arizona Historical Society, established a couple years earlier and located at Prescott.

It was through the Arizona Historical Society — which by this time had combined with the original Arizona Pioneers Society, also of Prescott, to form the original Arizona Pioneer and Historical Society — that many of the pioneers learned of Ehrenberg’s slaying by an unknown killer that year, at a stage station at Dos Palmas, California. Now, only a shadow remained of one of Arizona’s most important pioneers.

Herman Ehrenberg grave site (at right) at Dos Palmas, California.

A few years later, Michael Goldwater had the town of Mineral City renamed to Ehrenberg in his honor. Today, many people driving from Arizona to California along Interstate 10 pass through Ehrenberg, a very small town across the Colorado River from Blythe, California.

Happy birthday, Tucson. See a few important events in Tucson's history.