When long-time Tucsonans talk about the origins of Reid Park Zoo, the debate usually centers around the question of which came first, the peacock or the prairie dog? Well, the answer might be both.

Bob Charles, a University of Arizona student at the time who volunteered under Gene C. Reid, head of the Tucson Parks and Recreation Department, recalls that in 1962-63, while he was planting roses in the rose garden, he often heard peacocks making their distinctive sound — like a train rattle — in the park, although he didn’t see them. No known zoo existed at the park, then known as Randolph Park, at that time. A pair of peacocks, perhaps dumped there, may have wandered an area of the park freely.

What is known is that in April 1965, Gene C. Reid received prairie dogs from “Stump” Hamilton, director of the Lubbock Parks and Recreation Department in Texas. The little mammals were caught at the famous Prairie Dog Town in Lubbock, the first protected prairie dog colony of its kind.

Emerson Hall, second in command of the Tucson Parks and Recreation Department, who was friends with Hamilton, directed the proceedings of bringing the dogs to Tucson and assisting with creation of their new home. He might also have originally conceived the idea for Tucson’s Prairie Dog Town.

In late April 1965, workers finished the prairie dogs’ new living quarters in Randolph Park (now Reid Park), also called Prairie Dog Town, a large octagon-shaped rock and cement open arena filled with tons of dirt, large boulders, bushes and a few trees. In between the town and an octagon-shaped wall with a metal rail above it, surrounding the town, was a rock-bottomed moat filled with water to prevent the dogs from escaping. The first known exhibit of the future zoo was now open. (The town is now the World of Play area.)

The town was located southeast of present-day Reid Park Lake on what was a mound built in 1934 as an overlook by the Civilian Conservation Corps, Company 1809, which was stationed in Randolph Park. This company had transferred from Colorado and brought with them a bear cub named “Teddy,” possibly the first non-native animal to reside in the park.

Soon after the construction of Prairie Dog Town, as Reid put it, “we came by some peacocks and pheasants,” and constructed a cage near the prairie dogs to house them.

Reid continued, “Then someone gave us a monkey.” A telephone call was made to Tucson City Manager Mark Keane asking what to do with it, to which Keane replied, “Guess we’ll have to start a zoo.”

In April 1966, the Tucson Daily Citizen reported Reid was “building a walk-in-type children’s zoo. … Being placed just east of Prairie Dog Village, the zoo will be stocked with baby farm animals, all available to be petted.”

They continued, “This is a Reid-type project, being done without funds appropriated for its purpose by the City Council. It’s mainly by donation, under Reid’s entrepreneur and guidance. To survive, it needs the help of the community. Donations of any baby farm animals readily will be accepted.”

In July 1966, a staff writer from the newspaper returned to see the progress of Reid’s unofficial zoo. He described it as “... a bustling, fenced-off zoolet, echoing to the sounds of hammers and saws as workmen busily add to an already dense complex of cages and buildings.”

The buildings in this case were likely structures such as the Little Red Schoolhouse in the lamb’s pen, which had a sign that read “Mary’s Little Lamb” in a play on the nursery rhyme. Around this time, there was also a Peter Rabbit Farm and other corrals, each with a theme from popular children’s rhymes and stories.

There was at least one employee or volunteer assigned specifically to the “zoolet,” Signe Ann “Cookie” Lundstrom, a U of A student, at this point, who worked as a part-time keeper on the weekends.

Chuck Pettis recently remembered his involvement in adding a couple of animals to the little zoo. “Gene Reid approached the Palo Verde Kiwanis Club, which I was president of at the time in 1966, and asked for money to purchase blackbuck antelope.

“Within a couple of months, I went to the zoo, which had almost nothing in it at the time, and gave Reid the check for the purchase of the antelope. Afterwards we took a photograph of Reid and I standing near the ‘Blackbuck Antelope’ sign.”

In September 1966, big changes began to take place when the Randolph Park Children’s Zoo acquired Sabu, a 2-year-old elephant, via donation from the Conquistador Kiwanis Club. Carl Weese was hired to train the new elephant. Two years later the club purchased a companion for Sabu by the name of Connie.

In October 1966, along with the elephant, the animals the zoo was known to have were a monkey, prairie dogs, goats, skunks, raccoons, pigs, lambs and rabbits, as well as a variety of birds.

By January 1967 the zoo boasted of a large aviary as well as side cages that held more than 100 kinds of birds including barn owls, chickens, chuckers, guinea hens, parakeets, parrots, ravens, and a giant-sized French goose. Around this time the zoo also had turtles, ducks, coatimundi, ponies, foxes, llamas and a white-faced calf named Jennifer.

Chuck Pettis and Gene Reid at the then-new blackbuck antelope exhibit.

By April 1967 the zoo had added a Dromedary camel named “Sheik” (later came a companion named “Sheikla of Araby”); a pair of alligators, Brutus and Portia; and a couple of lion cubs. Other additions by this point were cattle, cats, a South American honey bear, porcupines, ringtail cats, opossums, bobcats, white rats and guinea pigs housed in an area well-shaded by trees.

The status of the unofficial city zoo changed In June 1967 when the City Council was going over the budget line by line and came to the item: City zoo — $49,404.

One of the councilmen asked, “What’s this? What zoo?” Reid replied, “It’s just a plain, ordinary zoo ... but with a little money you could make it into a real good zoo.” He then shared how this zoo was thrilling thousands of children and their parents. With those words, his endeavor received bipartisan support, with all saying “yes” to his share of the budget. It then became the city’s first official zoo.

While rumors have persisted for years that the City Council was unaware of the petting zoo until Reid requested that it be added to the city budget, this was little more than a zoological myth.

Jim Murphy, a city councilman at the time, recently shared: “I was aware of the petting zoo at Randolph Park prior to Reid’s submission for funds and I’m sure most if not all of the councilmen knew about it as well. It just wasn’t something that anyone brought up at the council meetings.”

In January 1968, Suzie Reif (nee Rohan) was hired on as staff zoologist looking after a wide variety of domesticated and wild animals, which by April included some 80 species and more than 500 animals including three seals, leopards, and a hippopotamus named Suzie. The zoo that was open 10 a.m. to 6 p.m. daily with no charge.

In June 1968, at the annual City Council budget meeting, Reid requested a zoo budget of $140,000, due in part to the immense growth of the zoological gardens. He was rejected and instead allotted $84,000. This decision on the part of the city fathers would have a detrimental effect later on.

In November 1968, Reid received a donation from Goodbody and Co., a Tucson investment firm, of three anteaters from a Ft. Wayne, Indiana zoo. Years later, due to the unusual success in breeding the giant anteaters, the zoo made it its logo.

In February 1969, Dr. Thomas O. “Doc” Miller, originally of Ohio,and a partner at the VCA Valley Animal Hospital, took the helm as the part-time zoo veterinary consultant, a role he would remain in for many years.

He would later be the inspiration for the “Doc Miller” statue at the zoo, located near the giraffe exhibit under the large mulberry tree. It consists of a veterinarian’s chair with a stethoscope hanging over the back, a cane leaning on the chair, and animals on the ground near the chair. The idea was originally conceived by zookeepers Karen (Bongratz) Toca and Joanna (Jones) Gradillas after Miller’s death.

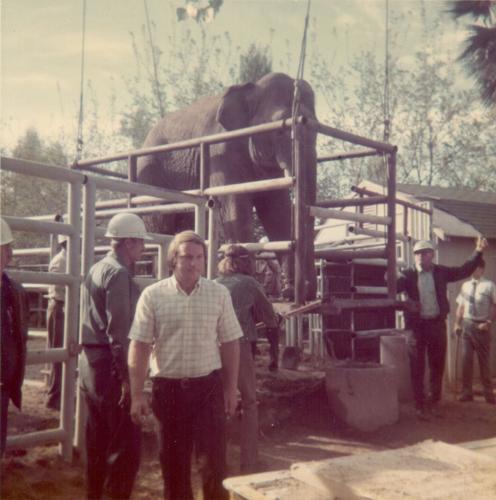

Sabu the elephant being moved to new enclosure in April 1973.

In August 1969, the zoo was in the midst of raising money to purchase two polar bear cubs from a Russian zoo when things began to unravel.

The following month, as the time approached for the animals to depart a Soviet Union zoo, animal activists attended City Council meetings in what was called “the first polar bear crisis in the history of the Arizona desert.”

They protested the plans, which called for a 10-by-12-foot cage, a small pool of water and no cooling of the deck on which bears normally like to sun. Later, the protesters were joined by the Tucson Audubon Society, the Nature Conservancy and the Sierra Club.

After the cubs, later named Eski and Mo-Mo, arrived in Tucson, Reid pointed out that the Humane Society regularly checked on the animals at the now 10-acre zoo. He said at least six top zoologists confirmed the polar bears could do well in Tucson.

But, as a result of the negative attention, around December 1969, the City Council appointed the nine-member Tucson Zoological Commission, including some of the zoo’s critics, to look into the facility. At that point, the zoo had a nine-member staff, about 600 animals, and operated on an annual budget of $128,000. The commission’s main objective was to come up with a master zoo plan to submit to city officials.

In August 1970, however, things got worse. Carl Weese, by this time zoo foreman, who had gained a reputation for fearlessness in dealing with his animals, was moving Sabu to another pen, away from his mate Connie, at the same time workers were working on a metal fence. The large elephant weighing somewhere between 4,000 and 6,000 pounds suddenly turned on him. Sabu slammed Weese to the ground, then threw him across the pen like a ragdoll, and followed up by smashing him against the metal fence, pinning him against it.

Soon after, Weese was dropped to the ground, and nearby staff dragged him to safety. Weese was rushed to Tucson Medical Center with severe bruises, a dislocated elbow on one arm and torn muscles on the other arm, but would return to work a little over a month later.

Sabu’s violent reaction to being moved or possibly to the constant banging of the metal fence around his pen concerned Reid. In fact, the director recommended to the zoo commission at a meeting that Sabu be traded to another zoo with a larger enclosure, compared to the 20-by-30 pen he was currently living in, since he was a potential danger to visitors and handlers in his current conditions.

After 30 minutes of discussion, the commission members, thinking it unlikely that another zoo would want a potentially dangerous animal, recommended the 6-year-old elephant be killed. It would be up to the mayor and City Council to approve or disapprove the death sentence.

It took less than 24 hours after word got out that individuals and groups began to challenge the commission’s recommendation of destroying the animal. Hundreds of grade school children sent handwritten letters and posters to the mayor and council’s offices begging, pleading and threatening not to vote for them in the future if Sabu’s life was ended.

Elephant siblings Meru, Penzi and Nandi play in the mud at Reid Park Zoo. Video courtesy Reid Park Zoo

Weese, who had been mauled by Sabu, came to his defense, stating publicly, “I’m not going to take this lying down. There’s no reason to destroy a healthy animal like that.”

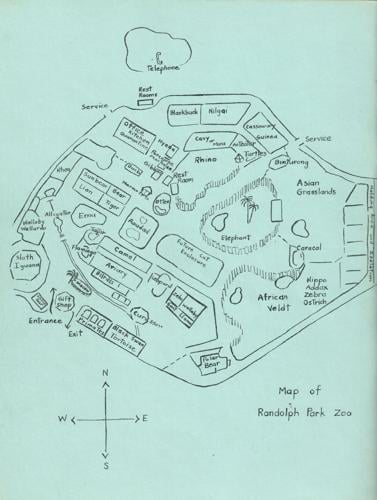

Randolph Park Zoo book map circa 1976.

Reid also said his department received “a large number of calls of concern and of offers of help for Sabu.”

Around December 1970, the City Council approved a death sentence — but it wasn’t for Tucson’s beloved elephant, but rather for the Tucson Zoological Commission.

Coming next Monday: Part Two