The zoo that would eventually be named Reid Park Zoo had no real budget for advertising early on, and the staff had to improvise to make Tucsonans aware of what it had to offer.

Garland Godbehere, a senior keeper, used to take the camel, Sheik, over to the Cactus Drive-in Theater (later called the De Anza Drive-In) on the southeast corner of Alvernon Way and 22nd Street. He allowed moviegoers to take pictures with the animal, while waiting for the movies to begin, as a way of promoting the zoo.

Sheik and Sheikla the camels in 1975.

That’s the story another zookeeper at the time, Marc Bruns, recalls Godbehere sharing with him.

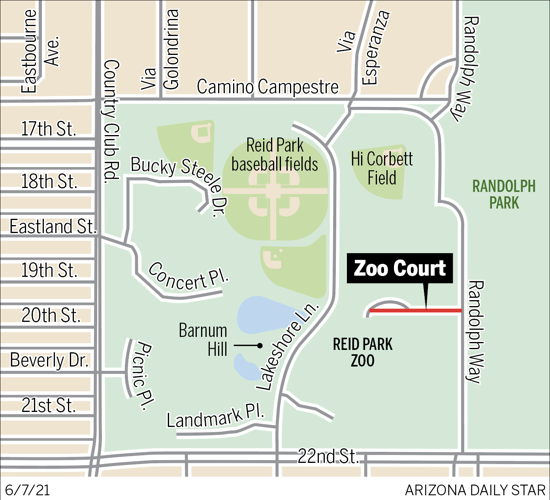

Bruns began his career at the zoo, then called the Randolph Park Children’s Zoo, in July 1971 as a Zookeeper I for the Tucson, Parks and Recreation Department, Zoo Division. There was stiff competition for the job, he recently recalled.

A zookeeper used to take a camel named Sheik to the Cactus Drive-in for moviegoers to take photos with, as a way to promote the zoo.

In spring 1971, Bruns was one of 60 hopefuls for two zookeeper positions who took a written exam at the University of Arizona Biology Building. He advanced to the second round as one of 15. “The second part of the test was administered at the zoo and consisted of more zoological questions, an agility test and an exhibit scenario question.” His scores got Bruns ranked No. 1 on the hire list. Gene Laos, the assistant director of parks, interviewed five finalists and Bruns and Barry Ames got the jobs. “We started at $3.22 an hour,” Bruns said.

Some other memories he shared were that the last couple of prairie dogs of the zoo’s original Prairie Dog Town were either sent to another zoo or let go free within a few months after he got hired. This enclosure about a year later became the South American exhibit that included sloth iguana, macaws, monitor lizard and rheas. The sitatunga (antelope) enclosure had a small pond that was filled with tilapia, the only fish in the zoo at that time, Bruns said.

He remembered when you first walked in the entrance, then located on the south side of the zoo, and turned immediately right, between the exterior chain link fence and the primate (large monkeys’) cages were two plum trees. The staff would pick fruit off the trees and feed it to the primates.

In August 1971, the zoo lost its second-in-command, Suzie Reif, after she was diagnosed with leukemia and had to retire.

In February 1972, Mike Flint, originally of Indiana, who studied zoology at the UA, was hired as the provisional curator, in a sense replacing Reif.

The following month, a Humane Society representative toured the zoo, which at this point had 150 species of animals and more than 600 animals.

The representative recommended that a full-time zoo director was needed, a 50-cent admission charge being considered would provide a limited contribution towards zoo improvement, and suggested the lion’s share of funds for improvements might come from a zoological society if one could be formed.

The Tucson City Council responded to the recommendations and approved an admission fee of 50 cents for patrons 17 and older, 25 cents for those 12 through 16, and free to get in for kids 11 and younger. The zoo constructed a small ticket booth at the entrance and began charging an admission fee for the first time on April 26, 1972.

By July 1972, James L. “Lynn” Swigert, a Naples, Florida zoologist, had been hired as the first full-time zoo superintendent. He had a 10-by-12-foot cubicle with dull green walls cooled by an anemic swamp cooler. His staff consisted of 13 full-time employees, possibly a few part-time ones, and a $192,000 budget.

In an interview given that month, he said the new elephant enclosure was estimated at $60,000 and would occupy one and a half acres. It would contain a large, cement-bottomed pond, surrounded by a grassed area and a barn hidden from view for when inclement weather required Sabu and Connie to seek shelter.

The actual move of the elephants to the new and much larger pen took place in April 1973. Both mammals were put into a standing tranquilization as planned and a 20-person crew and a 40-ton crane got the job done.

By this time, Swigert had written a 16-page zoo progress report. The elephant enclosure wasn’t the only one that had been expanded and improved.

Eight bird cages had been enlarged and landscaped to show four natural habitat areas and the zoo’s walk-through aviary had been remodeled and improved. It now featured a waterfall and tropical landscaping and could hold up to 300 birds without overcrowding. Also, nine separate areas were reseeded and 367 new plants and trees were planted, with much of the work carried out by Alex Flores, the zoo groundsman.

In June 1973, about a year after Swigert took over the zoo, he said he had reduced the animal count to about 325 animals, which in turn was believed to have handled overcrowding issues that had plagued the zoo.

In July 1973, the animal habitat expansion continued when the City Council approved spending $6,100 for an architect to draw up plans for a new and improved enclosure for polar bears Eski and Mo-Mo.

Swigert stated it would include an underwater display and a hidden cubbing area, separated from the public by a wide, deep, open moat. It would have no bars, would be 2,400 square feet of ground and would feature a 16-foot waterfall spilling into a 72,000-gallon swimming pool.

It wasn’t until May 1975 that the polar bear enclosure was completed and Eski and Mo-Mo were moved to their new home, however.

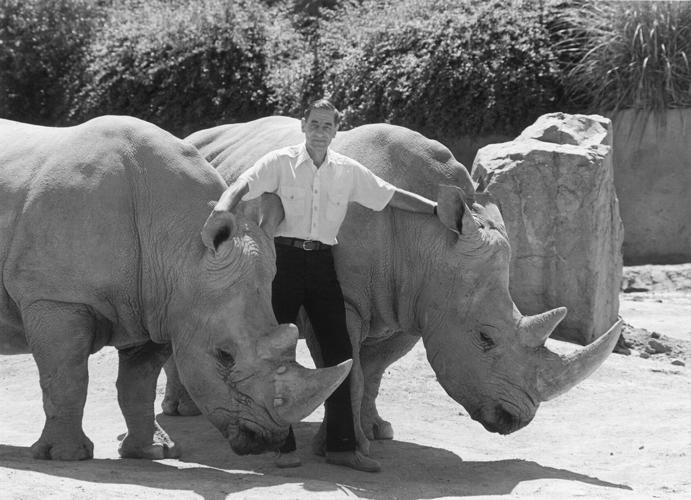

Mark Bruns reunites with Yebonga in 2022, many years after he was part of a crew that drove the rhino from the San Diego Zoo Wild Animal Park to live at Reid Park Zoo.

In March 1975, Swigert hired Joanna (Jones) Gradillas as a clerk-typist. Swigert told her she would likely be made a zookeeper trainee in a year or so, which is a role she much preferred, she recently recalled. In her free time she shadowed zookeepers to learn the job.

Around May 1975, Swigert left for the Jackson Zoological Park in Jackson, Mississippi.

At the time of his resignation, Tucson’s zoo occupied 12 acres and had approximately 300 to 350 animals. The employees were curator Mike Flint, a dietician, four senior keepers, seven keepers, and three keeper-trainees. Others on staff included ticket sellers, park guards, three maintenance workers and a groundsman. Employees including Alex Flores, Sandra Hein, Ann Dery, Gale (London) Ferrick, Juan Pallanes, Joe Sexton and John Stutz helped keep the zoo running smoothly.

In August 1975, Ivo Poglayen, a native of Germany who had a doctorate in zoology from the University of Vienna and had been head of the Rio Grande Zoo in Albuquerque, New Mexico, was named superintendent of the Tucson zoo at a salary of almost $15,000 a year.

One of the first items Poglayen had to deal with was the planning of a new animal hospital, already in the works. It would have isolation quarters for animals in quarantine, an operating room, X-ray facilities, a laboratory and space to allow visitors to observe infant animal care in the nursery.

The process would take several years with money approved by the City Council in May 1976 as part of a $750,000 expansion program. The building was completed in December 1978.

In October 1975, City Manager Joel D. Valdez proposed a zoological society. The council was presented with the society’s by-laws and endorsed its creation, although the council’s connection appears to have ended at this point.

On Nov. 26, 1975, Pat Crockett, Ruth J. Irving, Verna Carlson, Diane M. Boyle George C. Codd and Al Ganem were elected as directors of the auxiliary support organization for the Old Pueblo’s zoo to promote community awareness and provide financial support. In January 1976, the Friends of the Randolph Zoo Society, Inc. a nonprofit organization, was incorporated in Arizona.

The society would charge annual dues of $5 for individuals, $12 for families, $15 for organizations or businesses and $1,000 for lifetime memberships. In return for dues all members would be allowed free zoo admission. The Friends of Randolph Zoo Society, Inc. was later labeled the Tucson Zoological Society and it is now called the Reid Park Zoological Society.

The same month, Poglayen made arrangements with the San Diego Zoo Wild Animal Park to receive two southern white rhinoceroses on breeding loan.

Poglayen, Bruns, by this point promoted to a senior keeper, and a non-zoo staff driver headed out to San Diego in a Tucson Warehouse & Transfer Co. semi flatbed truck, paid for by zoo supporters, to pick up rhinos Zibulo and Yebonga, both under 4 years old and weighing 2,000 to 3,000 pounds apiece.

At the San Diego park, Poglayen and Bruns watched the rhinos being given a mild sedation via dart. With the use of heavy-duty rope, the Wild Animal Park staff managed to pull each rhino into their respective crate. After one final vet check, the trio was off into the night, to avoid the harsh heat. They stopped every couple of hours on the trip back to Tucson to check on the condition of the rhinos, a male and female lent indefinitely for the purpose of breeding.

The animals’ new home would be a remodeled enclosure previously occupied by a pair of bison. Visitors would be able to get as close as nine feet away. The Friends of the Randolph Zoo Society gave a $2,000 grant raised through donations to remodel the enclosure.

Yebonga, who was born in 1973 at the San Diego Wild Animal Park, has resided at Reid Park Zoo since this time and is truly worthy of the title “Queen of the Reid Park Zoo.”

By December 1976, Dorothy P. Maxson, a first-grade teacher at Blenman Elementary, had written, illustrated and published a coloring book, Randolph Park Zoo.

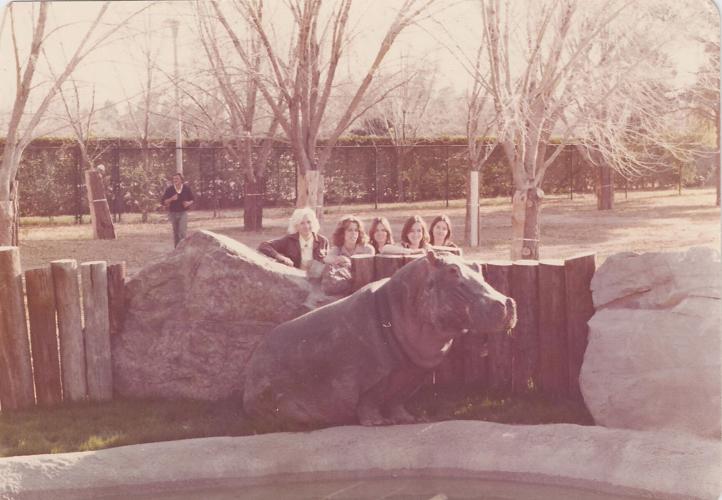

Suzie the hippo and staff, the day she was moved to the new exhibit African Veldt circa late 1978.

Maxson recently remembered, “I didn’t get paid for the work, but rather hoped the book would help others to understand and love the animals the way I do and remember them long after they have passed. The zoo is a wonderful gift to the Tucson community.”

It featured on the back cover a drawing of the zoo’s layout, including large sections of land being occupied by the rhino, elephant, African veldt (likely completed in late 1976 or early 1977) and Asian grasslands (completed in fall 1978) exhibits.

In June 1978, Gene C. Reid retired as director of the Tucson Parks and Recreation Department. Reid had started the whole thing (along with recreation superintendent Emerson Hall) with just a few prairie dogs and a desire to have a free children’s zoo in a central location that was accessible to all, including the poorest kids in Tucson.

Soon after his retirement, Randolph Park was renamed Gene C. Reid Park, and the Randolph Park Zoo became the Reid Park Zoo.

Reid Park Zoo's elephant calf Meru loves playtime and exploring her habitat, including figuring out how to get over logs. Video courtesy Reid Park Zoo