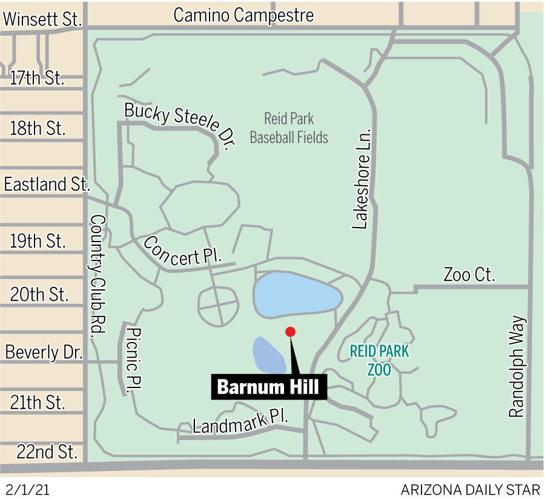

Barnum Hill, a grassy mound with man-made waterfalls popular with Tucson parkgoers, is in the news these days because, controversially, it would be taken in by Reid Park Zoo’s planned expansion.

The story of its namesake, Willis E. Barnum Sr., a prominent local civic leader starting in the early 1900s, is also a tale of Tucson’s histories of golf, scouting, motorcar sales, development, war efforts and business ties with Mexico.

It also explains how this third cousin of famous circus man P.T. Barnum wound up in the Old Pueblo in the first place. Some of that will unfold in the second part of this article, on Tuesday, Feb. 2, in the Star.

Today, we will highlight how golf came to be king in Tucson, how Willis E. Barnum Sr. helped make that happen and how that led to his namesake hill where, today, Tucsonans sit to soak in the sun or feed the ducks.

"A weather event can always be exciting for the elephants, but a first snow is always special for a baby elephant," said director of zoological operations Sue Tygielski. "Penzi took the snowflakes as a cue to play in the stream and slip and slide in the mud. Even her older sister, Nandi, could not resist a roll in the mud on a snowy day." Video courtesy of Reid Park Zoo, taken on Jan. 26, 2021

Long push for a public municipal course

The idea for the first public golf course for Tucson appears to have its origins around May 1, 1923, when the Arizona Daily Star reported plans were being made for a small golf course, with the possibility of adding croquet, tennis and horseshoe pitching courts later on, for locals and winter visitors alike.

Willie Mann, a professional golfer, had conceived the idea for the municipal golf course that would be a nine-hole, par-36, 3,415-yards-long course, on 129 acres on First Avenue north of Adams Street. Mann said the nine holes would cost just 35 cents to play, and clubs could be rented if needed.

While these plans sounded great to many, the concept never got out of the sand trap.

The next month, F.E.A. Kimball (namesake of Mount Kimball), head of the Summerhaven Land and Improvement Co. on Mount Lemmon, constructed a six-hole golf links. The course was on 50 acres, a mix of Forest Service and private land, with two trout streams running through the acreage. The links were about 7,800 feet above sea level, making it the highest golf course in the world, according to a June 22, 1923, Star article.

But, considering one had to drive to Oracle first and then drive up the backside of Mount Lemmon on a rough road, the course was hardly accessible to the average Tucsonan and was more of a novelty.

The ball started rolling again in the summer of 1924, when it was learned that a lease held by Barnum for 480 acres of state land, just south of Broadway, was due to expire and could potentially be up for sale. Barnum, while working in real estate, had taken out lease #04729 for the land in 1919.

On June 4, legal advisor to the city Ben C. Hill — who originally conceived the idea for a public course on this ground — filed an application for this state land, with the intention of the city purchasing it for a public golf course.

After the application was filed, the matter was addressed with Mayor Rudolf Rasmessen (1921-1924) and the council. But in the meantime, Arizona renewed its lease with Barnum, who had built a home on the property.

Tourists find “little to amuse themselves”

With this land no longer available, in December 1924, W.B. Hutchinson, a golf professional, offered 100 acres at present-day Grande Avenue and Colorado Street to the city for a municipal golf course. His conditions were that it be named the Santa Catalina Course and that Tucson could use the land for five years for free and then buy or lease it for a small amount.

“There is little attraction here for the sportsman ... and the visiting tourists who are in the city for the winter months find little to amuse themselves,” Hutchison said. Apparently, the city did not take advantage of this offer.

In 1925, Leighton Kramer (namesake of Leighton Place and Kramer Avenue), who had recently built a polo field on his property near Elm Street and Campbell Avenue, offered a long-term lease on 80 acres surrounding the polo field at $1 a year. The city accepted.

Business leaders were so confident they had found their golfers’ heaven, they commissioned artist Lone Wolf to paint a portrait of Kramer for donating the land and because he had founded the popular Tucson rodeo.

In addition, the head of the Tucson Chamber of Commerce took 140 Los Angeles businessmen, on a tour of the city, to the spot where the future links would be constructed.

High-stakes bidding

City clearing work began in April 1925, but soon it was determined that not all of the land was suitable for a golf course. Kramer talked Charles Blenman (namesake of Blenman School) into offering 80 acres of his land that adjoined Kramer’s property. Work began on blueprints for the course layout.

But, by this time, Barnum had agreed to give up his lease on his very desirable 480 acres on Broadway and allow the state to sell it.

It’s unknown why he changed his mind, but it likely had to do with the tourist hotel — soon to be called El Conquistador Hotel — that was going to be constructed just north of Broadway. A public golf course and park nearby would help this hotel thrive and the Old Pueblo to become a winter vacation destination.

On Sept. 12, 1925, the mayor and City Council held a special session in front of the Pima County Courthouse. They had authorized Hill, the city attorney, to bid a set amount per acre on the state-owned land. But they would remain close by in case they needed to authorize a higher bid when it all began at 11 o’clock. They were willing to pay $36,000 or more.

Barnum still held the lease and therefore had priority rights in the bidding. He had agreed to make an offer, if necessary, at an amount permitting himself a $2,000 profit, and to then sell to the city. This deal was struck as a safety net because business syndicates had formed to obtain the land, but they apparently never showed up to the courthouse.

As the Tucson Citizen reported, “As there was no serious opposition in the bidding, the city secured the desirable tract at the absurdly small sum of $14.50 an acre for the land … (plus $7,800 for) the improvements on the land. … The city has a term of 38 years in which to pay for the land.”

While the often-told story about Barnum purchasing the land for the financially stricken municipal government doesn’t appear to be true, he still gave up the opportunity to buy the land for himself and sell for a much higher price to a developer. Nearby land had sold a few months earlier for close to $200 an acre.

For Whom to name it?

After the deed was done, as they say, Tucsonans began to talk about whom the park and golf links should be named for. The Star suggested the late William Jennings Bryan, former U.S. secretary of state. Bryan had close ties to Tucson because his son William Jr. attended the University of Arizona and became a Tucson lawyer.

The Star also suggested a Tucson pioneer, Col. Epes Randolph, who had died a few years earlier, “whose memory might be honored with the new park.” In December 1925, the Tucson City Council passed a resolution naming the 480 acres in honor of Epes Randolph.

By June 1926, the supervisor of construction, along with 14 laborers and a power grader, had completed the fairways, hazards and greens of six holes. The remodeling of Barnum’s old house into a clubhouse, to include living quarters for the course manager, restrooms, showers and lockers, as well as the deepening of the well, then 117 feet deep, were planned.

On Oct. 24, 1926, Mayor John E. White formally dedicated the new nine-hole golf course that had greens of the oil-sand type, fairways that were bare because water was too difficult to get in that location to maintain a grass fairway, and a limited number of hazards.

The dedication was attended by more than 100 people. A foursome match was played by local stars competing for the Epes Randolph Cup, given by his widow Eleanor Randolph.

Inspired by a famed L.A. park

On Oct. 31, 1936, Barnum attended the opening of the new Randolph Municipal Golf Course, after an expansion and remodeling project that expanded the course to 18 holes and grassed the greens, fairways and tees.

A complete sprinkler system, including the installation of five miles of pipes, a 1,000,000-gallon water reservoir and a pumping plant, were installed as well. Luminaries U.S. Sen. Carl Hayden and Tucson Mayor Henry O. Jaastad gave speeches at the clubhouse.

Dell Urich, club pro at the time, gave the mayor some lessons on the new grass course.

In 1960, Barnum had the honor of hitting the first ball to open the first half of a new course — now called Dell Urich Golf Course. Many months later, the old clubhouse was closed down, and a new one located on Alvernon Way and Hayne Street opened to the public.

Around the same time, Gene C. Reid (namesake of Reid Park, then called Randolph Park), acting director of the Tucson Parks and Recreation Department, completed the park’s north pond, today known as Reid Park Lake.

He felt something was still missing, though, and recalled the waterfalls operating at Los Angeles’ Griffith Park. His problem was that you can’t have waterfalls without elevation and the Tucson park was as flat as a pancake.

Reid contacted the L.M. White Contracting Co., which had an excess of dirt from a street paving contract. They hauled the dirt over to the park and built a 25-foot man-made hill just south of the north pond. When finished, they blanketed the hill with top soil.

Reid then used hundreds of large stones he had obtained from a Miracle Mile improvement project to construct the waterfalls and created one of the city’s most unique nature spots. This later became Barnum Hill.

Zoo Takeover

This month, the Reid Park Zoo is scheduled to take over 3½ acres including the hill as part of its expansion.

Barnum’s grandson-in-law, Bruce Billings, shared in an interview: “If the zoo decides to take Barnum Hill into its enclosure, which would only allow paying customers to see it, then another option might be to move the ‘Barnum’ name to the golf clubhouse, since the original clubhouse was set up in his old house on the property, and a historical marker could be added explaining his contributions to our town.”

Gallery: Water fills the desert at these spots around Tucson:

Photos: Water fills the desert at these spots around Tucson

Lakeside Park, Tucson

Updated

A father fishes with his two sons at Chuck Ford Lakeside Park, 8201 E. Stella Rd., in Tucson, Ariz. on Nov. 17, 2020. Chuck Ford Lakeside Park, an urban lake on the southeast side of town, is a popular spot for walking and fishing. The lake is stocked with catfish, trout, bass and sunfish.

Lakeside Park, Tucson

Updated

A duck runs on water at Chuck Ford Lakeside Park, 8201 E. Stella Rd., in Tucson, Ariz. on Nov. 17, 2020. Chuck Ford Lakeside Park, an urban lake on the southeast side of town, is a popular spot for walking and fishing.

Lakeside Park, Tucson

Updated

While fishing with family members, Jose Saenz places a caught rainbow trout in a basket at Chuck Ford Lakeside Park, 8201 E. Stella Rd., in Tucson, Ariz. on Nov. 17, 2020. Chuck Ford Lakeside Park, an urban lake on the southeast side of town, is a popular spot for walking and fishing. The lake is stocked with catfish, trout, bass and sunfish.

Lakeside Park, Tucson

Updated

A fisherman waits for a fish to bite their lure at Chuck Ford Lakeside Park, 8201 E. Stella Rd., in Tucson, Ariz. on Nov. 17, 2020. Chuck Ford Lakeside Park, an urban lake on the southeast side of town, is a popular spot for walking and fishing.

Lakeside Park, Tucson

Updated

The reflection of Chuck Ford Lake shows in avid fisherman Richard Espinoza's sunglasses while Espinoza fishes for trout at Chuck Ford Lakeside Park, 8201 E. Stella Rd., in Tucson, Ariz. on Nov. 17, 2020. Chuck Ford Lakeside Park, an urban lake on the southeast side of town, is a popular spot for walking and fishing. The lake is stocked with catfish, trout, bass and sunfish.

Lakeside Park, Tucson

Updated

A person walks around the lake at Chuck Ford Lakeside Park, 8201 E. Stella Rd., in Tucson, Ariz. on Nov. 17, 2020. Chuck Ford Lakeside Park, an urban lake on the southeast side of town, is a popular spot for walking and fishing.

Lakeside Park, Tucson

Updated

While fishing with her family, Aziza Ramirez waits for a fish to bite her lure at Chuck Ford Lakeside Park, 8201 E. Stella Rd., in Tucson, Ariz. on Nov. 17, 2020. Chuck Ford Lakeside Park, an urban lake on the southeast side of town, is a popular spot for walking and fishing.

Agua Caliente Park, Tucson

Updated

Several resident ducks ply the waters of the main pond as sun sets at Agua Caliente Park, Tucson, Ariz., November 17, 2020. The park is one of the most popular bird watching sites in the county.

Agua Caliente Park, Tucson

Updated

Park goers stop for photos of a pack of javalina roaming the park just before sunset at Agua Caliente Park, Tucson, Ariz., November 17, 2020.

Agua Caliente Park, Tucson

Updated

A pack of javalina rush for the trees after getting spooked while nosing around the lawn for food at Agua Caliente Park, Tucson, Ariz., November 17, 2020.

Agua Caliente Park, Tucson

Updated

The sun goes down and the bats come out over the main pond at Agua Caliente Park, Tucson, Ariz., November 17, 2020.

Agua Caliente Park, Tucson

Updated

The island in the main pond has been renovated and the bridge completely replaced at Agua Caliente Park, Tucson, Ariz., November 17, 2020.

Agua Caliente Park, Tucson

Updated

A park patron and his dog stroll along the paths on the shores of the main pond at Agua Caliente Park, Tucson, Ariz., November 17, 2020.

Agua Caliente Park, Tucson

Updated

Some of the wetland vegetation is beginning to reassert a hold after months of work to restore and renovate the main pond at Agua Caliente Park, Tucson, Ariz., November 17, 2020.

Agua Caliente Park, Tucson

Updated

Bernie Kanavage and Toby take a break from their evening walk on the bank of the main pond at Agua Caliente Park, Tucson, Ariz., November 17, 2020. The main pond was recently restored, a major renovation that shut the park down for months in late 2019.

Agua Caliente Park, Tucson

Updated

A pair of park goers get close-ups from an obliging duck along the shores of the main pond at Agua Caliente Park, Tucson, Ariz., November 17, 2020.

Agua Caliente Park, Tucson

Updated

Sun set over the main pond at Agua Caliente Park, Tucson, Ariz., November 17, 2020.

Santa Cruz River, Tucson

Updated

Water flows in the Santa Cruz River south of downtown Tucson, Ariz. on November 16, 2020. The addition of reclaimed water to the Santa Cruz River has hastened the return of wildlife.

Santa Cruz River, Tucson

Updated

A cyclist rides along The Loop as water flows in the Santa Cruz River near the Crossroads at Silverbell District Park, in Marana, Ariz. on November 18, 2020.

Santa Cruz River, Tucson

Updated

A heron sits by the water in the Santa Cruz River near the Crossroads at Silverbell District Park, in Marana, Ariz. on November 18, 2020.

Santa Cruz River, Tucson

Updated

Water flows in the Santa Cruz River south of downtown Tucson, Ariz. on November 16, 2020.

Santa Cruz River, Tucson

Updated

Water flows in the Santa Cruz River near the Crossroads at Silverbell District Park, in Marana, Ariz. on November 18, 2020.

Santa Cruz River, Tucson

Updated

Water flows in the Santa Cruz River south of downtown Tucson, Ariz. on November 16, 2020.

Santa Cruz River, Tucson

Updated

A Vermillion flycatcher rests on a branch along the Santa Cruz River south of downtown Tucson, Ariz. on November 16, 2020.

Santa Cruz River, Tucson

Updated

A bird rests on a branch of a tree along the Santa Cruz River near the Crossroads at Silverbell District Park, in Marana, Ariz. on November 18, 2020.

Santa Cruz River, Tucson

Updated

Water flows in the Santa Cruz River near the Crossroads at Silverbell District Park, in Marana, Ariz. on November 18, 2020.

Sweetwater Wetlands, Tucson

Updated

Water flows near the entrance at the Sweetwater Wetlands, 2511 W. Sweetwater Drive, in Tucson, Ariz. on November 17, 2020.

Sweetwater Wetlands, Tucson

Updated

Ducks swim in one of the bodies of water at the Sweetwater Wetlands, 2511 W. Sweetwater Drive, in Tucson, Ariz. on November 17, 2020.

Sweetwater Wetlands, Tucson

Updated

Libby Sullivan, left, and Sue Bridgemon walk along one of the trails at the Sweetwater Wetlands, 2511 W. Sweetwater Drive, in Tucson, Ariz. on November 17, 2020.

Sweetwater Wetlands, Tucson

Updated

Libby Sullivan, left, and Sue Bridgemon do some birdwatching at the Sweetwater Wetlands, 2511 W. Sweetwater Drive, in Tucson, Ariz. on November 17, 2020.

Sweetwater Wetlands, Tucson

Updated

A duck flight at Sweetwater Wetlands, 2511 W. Sweetwater Drive, in Tucson, Ariz. on November 17, 2020.

Sweetwater Wetlands, Tucson

Updated

Cattails grow near a body of water at the Sweetwater Wetlands, 2511 W. Sweetwater Drive, in Tucson, Ariz. on November 17, 2020.

Sweetwater Wetlands, Tucson

Updated

Ren Sullivan watches a group of ducks at the Sweetwater Wetlands, 2511 W. Sweetwater Drive, in Tucson, Ariz. on November 17, 2020.

Sweetwater Wetlands, Tucson

Updated

Sunlight breaks through the trees at the Sweetwater Wetlands, 2511 W. Sweetwater Drive, in Tucson, Ariz. on November 17, 2020.

Reid Park, Tucson

Updated

James DeDitius points at ducks as he sits with caregiver Mary Figueroa on a bench next to a lake at Reid Park, on March 17, 2020.

Reid Park, Tucson

Updated

The city's new 4.5 million gallon lake and storage basin at Randolph (now Reid) Park, Tucson, in December, 1959.

Silverbell Lake, Tucson

Updated

The Arizona Game and Fish Department brought in 14,300 pounds of catfish from Arkansas to restock 21 lakes in the Core Community Fishing Program in Tucson and Phoenix. These catfish were dumped into Silverbell Lake on April 03, 2015.

Silverbell Lake, Tucson

Updated

Jim Skay fishes at Silverbell Lake, on March 13, 2020.

Silverbell Lake, Tucson

Updated

In this 2016 photo, Nathaniel Ortega, left, grins while his grandfather Michael Ortega helps remove a fish from his line during a fishing clinic at Silverbell Lake, located in Christopher Columbus Park at 4600 N. Silverbell Rd. in Tucson, Ariz. Nathaniel's catch was the first catfish of the day.

Sahuarita Lake

Updated

A person walks along Sahuarita Lake on March 5, 2020.

Sahuarita Lake

Updated

Ted Moreno reels in a line while fishing at Lake Sahuarita, on March 5, 2020. Moreno, who lives in Tucson generally goes between Lake Sahuarita and Kennedy Lake to fish for trout during the fall and winter months.

Sahuarita Lake

Updated

Sahuarita Lake in the town of Sahuarita south of Tucson is popular with anglers, walkers, cyclists and others and its waters range from dazzling blue to aquamarine depending on the light.

Sahuarita Lake

Updated

In this 2001 photo, Dan Hampshire works on the top designs of a 34-foot monument tower at the entrance to Rancho Sahuarita, an 8,000 home project on 2,500 acres that includes a yet-to-be-filled 10-acre lake (in background).

Sahuarita Lake

Updated

In this 2013 photo, a couple walk around Sahuarita Lake Park, 15466 S. Rancho Sahuarita Blvd.