Thanks to the ingenuity of Arizona farmers and scientists using environmentally-friendly methods, U.S.-grown cotton is free of its major non-native pest, the pink bollworm.

The victory in the more than 100-year battle with the pest was announced in the fall by the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

The pests were so destructive that “there are many people who think the cotton industry would have collapsed years ago,” said Peter Ellsworth, director of the Arizona Pest Management Center.

But now, this is the first and only place in the world to eradicate the pink bollworm, said Bruce Tabashnik, University of Arizona regents’ professor and head of the entomology department. He was a member of the advisory committee that provided scientific advice about eradication and has researched the pink bollworm for more than two decades.

A powerful pest

The pink bollworm as an adult is a small gray moth, but it is most destructive as a caterpillar when it eats through cotton bolls. The pest costs growers tens of millions of dollars a year in damaged crops and preventative measures, according to the USDA.

The pink bollworm was first detected in Texas in 1917, then gradually migrated west, according to the National Cotton Council of America. By 1965, the pest was established in Southern California, Western Arizona and northwestern Mexico.

A pink bollworm moth (about one-third-of-an-inch long) on a cotton boll.

“Practice showed that pink bollworm thrived here (in Arizona) better than anywhere else in the world,” Ellsworth said. While scientists don’t know for sure, this likely has to do with our warm, dry climate and long growing seasons.

Until the late ’80s, management was only possible because farmers sprayed pesticide an average of 12 times per year, and about nine of those were specifically to thwart the pink bollworm. But individual farmers could spray up to 25 times a year and never control the pests, Ellsworth said.

They were also required to annually plow down their fields to prevent many kinds of pests, including the pink bollworm, from gaining a foothold.

The fight got harder, albeit healthier, in the early ’90s when the Environmental Protection Agency began reviewing some kinds of carcinogenic pesticides, causing manufacturers to withdraw their pesticides from the marketplace, said Paul “Paco” Ollerton, a farmer in Pinal County and current board chair for the Arizona Cotton Growers Association.

With their defenses down, “some (growers) would have fields that weren’t even picked, but it looked like they were,” Ollerton said.

A new technology

The dire situation started to turn in 1996 when Monsanto rolled out its first iteration of Bt cotton technology, which is genetically engineered to contain a toxin lethal to a few varieties of pests, of which the pink bollworm was the most important in Arizona, Tabashnik said.

But with this technology came a necessary mandate. At least 4 percent of a farmer’s cotton crop was required by the EPA to be non-Bt cotton. These were called refuges.

A pink bollworm caterpillar (about half-an-inch long) emerging after devouring the seeds inside a cotton boll.

“Refuges are just ordinary cotton,” but they are important because they delay the evolution of the pest’s genetic resistance to the Bt cotton toxin, Tabashnik said.

Bt cotton is designed to kill the typical pink bollworm, but planting refuges spares some. Allowing some genetically typical pink bollworms to live and mate with the rare resistant ones delays the evolution of resistance within the population to the Bt cotton toxin.

Without refuges, the insects that just happen to have a mutation in their DNA that makes them resistant to the toxin would be the sole survivors. They’d mate and pass down their resistance to subsequent generations. The technology would quickly become obsolete.

Which is exactly what happened in India. Many Indian farmers chose to not plant refuges despite a government mandate. The pests developed resistance in six years. Within another 10 years, pink bollworms in the region were also resistant to the second iteration of genetically engineered cotton, which contains two different Bt toxins.

UA researchers were tasked with tracking any emerging resistance in the U.S. and across the globe, Tabashnik said.

Because American farmers complied with the refuge strategy, the pink bollworm population fell by 90 percent in 10 years.

When farmers saw that the pests were weakened, they said, “We have our boots on their necks, let’s just finish them off,” Tabashnik said.

But the idea was “contentious,” as Ellsworth put it. Eradication is simply hard, and the Bt cotton was already making a big difference.

But by 2006, scientists and farmers came together to create a grand plan. Minds were changed, and it was agreed to give eradication a shot. The Pink Bollworm Technical Advisory Committee was formed and the eradication was implemented by the USDA and the Arizona Cotton Research and Protection Council.

Since the absence of a pest can’t be proven, the committee had to set the definition of eradication: “No live, wild pink bollworm detected for four years in a row,” Tabashnik said. “And in 2015 we passed that.” Last October, it was officially declared eradicated.

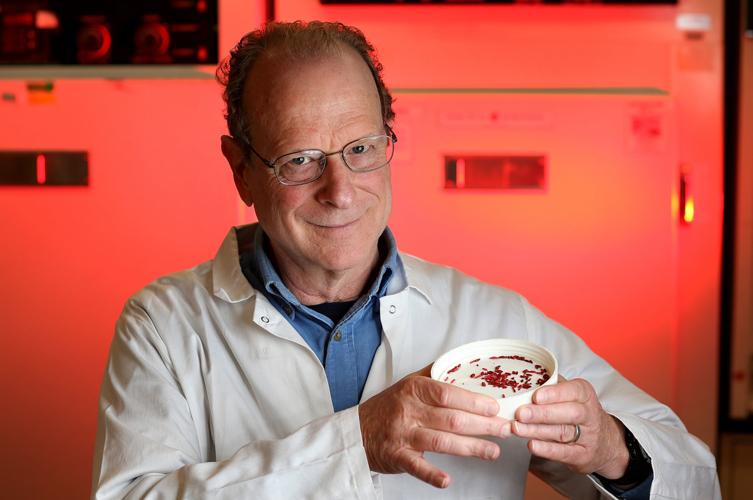

“The whole cotton ecosystem has been turned around,” says Bruce Tabashnik, regents professor and UA department of entomology head, with pesticide use drastically reduced.

The plan

Farmers approached Tabashnik and said, “Here’s what we’re going to do. Do you think it’s going to work?” he recalled.

They planned to unleash billions of sterile female pink bollworm moths over their fields, overwhelming any reproductive population.

The idea of waiving the refuge requirement and releasing sterile moths made him nervous. Based on his training and experience as a biologist, it’s very difficult to eradicate a well-established pest, he said.

So when the farmers asked him to see if it would work using a computer simulation, he was relieved. He said the simulations would show them that his hunch was justified.

But no matter how they ran the simulation under realistic circumstances, it worked every time. Tabashnik was convinced and became part of the eradication team.

The sterile moths were released by the billions.

The model predicted that eradication would occur in two years. It took slightly longer in reality because the program was rolled out in phases across the state, but it was a huge success.

Ellsworth also noted that the eradication plan wouldn’t have even gotten off the ground if Mexican growers along the border hadn’t participated. There would have been no point in trying to eradicate the pink bollworm without their cooperation, he said.

Bruce Tabashnik, regents professor and head of the Department of Entomology, shows the damage caused by a pink bollworm, right, against a normal cotton boll, left, in the department’s lab on the University of Arizona campus, Dec. 20, 2018, in Tucson, Ariz. The worm, which affects cotton bolls, was declared eradicated on Oct. 19 by the United States Secretary of Agriculture.

The upshot

The last time that Arizona growers had to spray insecticide against the pink bollworm was more than a decade ago.

And the less insecticide the better, Tabashnik said, because its absence allows natural predators of other pests to return and control the population in a natural way.

“The whole cotton ecosystem has been turned around,” he said.

“This is the lowest level of insecticide use in Arizona in nearly 40 years,” said Ellsworth.

The number of average sprays a year has fallen from 12 to two, Ellsworth said, a “huge reduction,” and the sprays that are used now are much less harmful than the ones used in 1990 because they are toxic only to the target pests.

Moreover, “We’ve withheld 25 million pounds of insecticide active ingredient,” he said. “And that’s just the active ingredient, just like bleach has a small percentage of hypochlorite. In reality, it’s hundreds of millions of gallons of product.”

The last time a pink bollworm was trapped was 2012, not just in Arizona, but in the whole zone of eradication: California, Texas, New Mexico, Arizona and northern Mexico.

Ellsworth estimates that Arizona farmers have saved $542 million between 1996 and 2016, and the gains have only continued.

“For all the arrows thrown at GMOs, we (Arizona) really are the poster child for successful engineering technology and,” this is key, Ellsworth said, “proper stewardship of that technology.”

Now farmers can grow cotton for longer stretches of time and use up every ray of sunshine. Ellsworth said he used to tell farmers they couldn’t grow the whole season for fear of fostering an overwhelming insect population.

“Now, per unit of water and land, they can produce more, which is good for everyone, the environment and their pocketbooks,” he said.

He also noted that none of this would have been possible if the problem hadn’t been tackled as a system; other pests were brought under control as well, including the Lygus bug and silverleaf whitefly.

“The principles of the tech are available to everybody,” Tabashnik said. “But pulling it off as well as it was here is remarkable. ... It was collaboration among cotton growers, the biotech industry, the USDA, the Arizona Department of Agriculture, the Arizona Cotton Research and Protection Council and UA extension and research. If you don’t have the collaboration and infrastructure, it won’t work.”

With this success behind them, farmers are looking forward. “There’s always something on the horizon,” Ollerton said.

He noted that the pink bollworm resistance to Bt cotton in Asia is a concern.

But one thing Ollerton and other Arizona farmers took away was the importance of being proactive.