A University of Arizona researcher has been working for decades to abate a serious disease that affects a disproportionate number of Hispanics.

To further this work, Dr. Diego Martin and his team are applying for a $12 million, five-year cancer research grant from the National Institutes of Health, in part to test a newly developed class of anti-diabetes drug’s ability to prevent the progression of what’s called nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. The grant money will be divided between two other investigations into breast and cervical cancer.

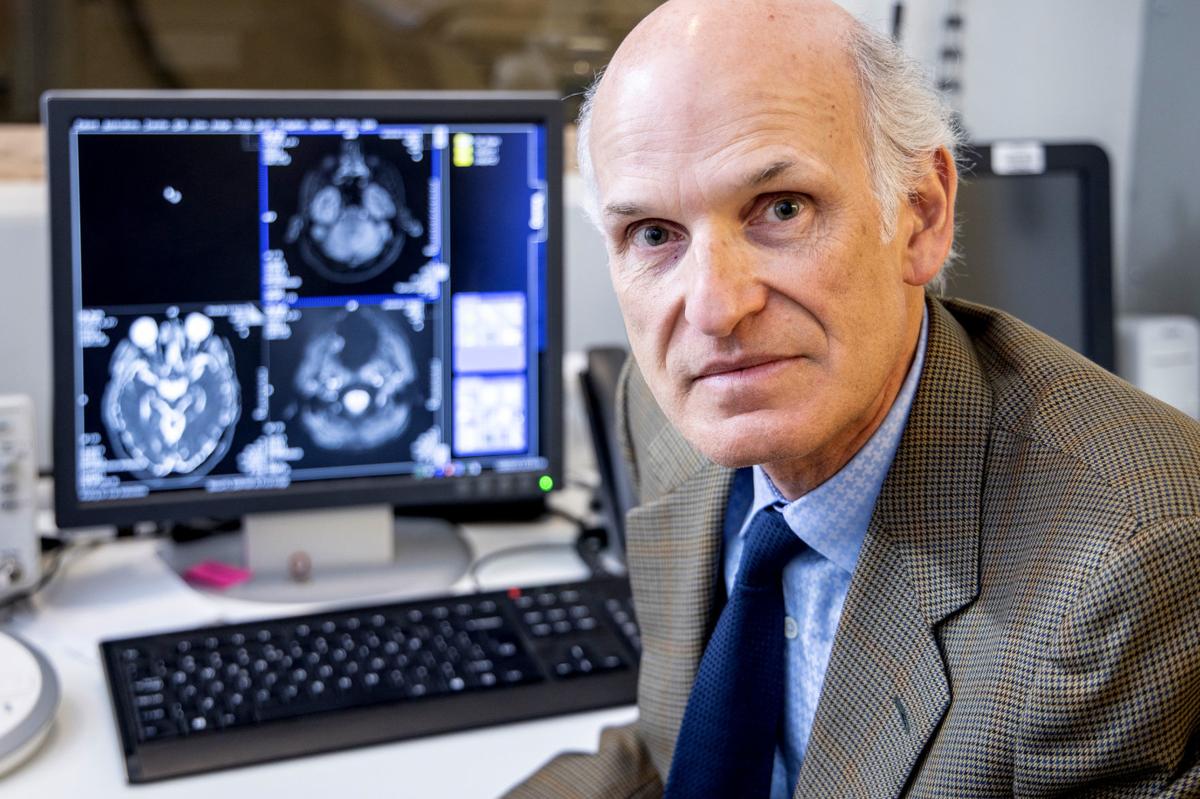

Martin, who works in the department of medical imaging, is an internationally recognized leader in magnetic resonance imaging for disease diagnosis and the development of noninvasive methods of early disease detection and measurement. Dr. Maria Altbach is his main collaborator and vice chair of the department.

Obesity — a common cause of the disease — is on the rise across all races, ethnicities and age groups in America, Martin stressed.

Consequentially, between one-fourth and one-third of American adults have fatty liver, experts agree. Some describe it as an epidemic.

Alone, fatty liver may not be dangerous, but about 20 percent of those with fatty liver will have it develop into a more dangerous condition, such as fatty liver disease, which includes damage and inflammation of the liver. This can eventually develop into liver failure or cancer.

“Historically, the biggest driver of liver disease was alcohol. Then it became viral hepatitis,” Martin said. “Now we have treatments for those, so the biggest driver is obesity.”

Overweight and obesity can also cause other metabolic syndromes — which are marked by high blood pressure, high levels of bad cholesterol, insulin resistance and large amounts of belly fat — including diabetes, stroke, heart disease and kidney disease.

“Hispanics as a group have a propensity toward obesity and overweight,” according to Martin, who is Hispanic. And according to the Mayo Clinic, Mexican-Americans appear to be at the greatest risk of developing metabolic syndrome.

This is caused by a combination of factors including cultural dietary habits, socio-economic status and limited access to health care, said Jorge Gomez, associate director of the UA Center for Elimination of Border Health Disparities and co-leader on the grant application.

Disease risk within this population is compounded by genetics. “For the same level of obesity as a non-Hispanic, they are also more likely to get nonalcoholic liver disease and progression,” Martin said.

At that point, the only cure is a liver transplant. However, a Hispanic individual is less likely than someone in the general population to get a transplant.

This situation is only expected to become more urgent unless some intervention is developed. Hispanics constitute nearly 20 percent of the U.S. population, making it the largest ethnic or racial minority in the country, and that proportion is expected to swell in the coming decades.

In Tucson, about 40 percent of the population is Hispanic, according to federal census data. “Being in this community, these are problems we need to face,” Martin said. “This university has a responsibility in this community. My department is very focused on these kinds of problems.”

The solution

Diet and exercise can be effective in treating fatty liver in the short term, Martin said, but he wants a long-term, cost-effective solution. “We’re looking at a drug that we think will be effective.”

The challenge is to prove it.

“That’s where precision diagnostics are needed,” he said. Precision diagnostics are exactly what Martin and his team are known for.

They’ve been developing fast and precise MRI technology to perform an array of measures for fatty liver disease, including the ability to determine the percentage of liver fat. The aim is to replace insensitive blood tests and invasive biopsies.

Traditionally, when people see a doctor for general abdominal pain, they’ll have their blood drawn for signs of liver damage. But the test is not always reliable. Martin believes that liver disease flares and subsides, and if you test someone on a day the disease is not flaring, it can give a false negative.

Moreover, people might not even get screened because they are not yet feeling pain.

“It’s a silent disease,” Martin said. “Years can go by after a false negative test. When a patient finally does feel pain, they could have advanced liver disease and cancer.”

Alternatively, if a test comes back positive, many doctors will order a biopsy. But biopsies have their own challenges — they’re invasive, can cause complications and are time-consuming.

Martin and his team’s MRI technique can catch fatty liver before a patient experiences symptoms and do it quickly. He and his team are also know for developing ultra-fast imaging.

“I believe that we’re the first center that has systematically used MRI in every single patient to measure fatty liver disease,” he said. His team has screened tens of thousands of patients using his technology.

This new class of anti-diabetes drug causes people to shed calories that would otherwise contribute to their weight. He believes that because it works for one metabolic syndrome, it could help reverse another. Martin hesitated to disclose the drug’s name because his team has yet to publish his results, which are still hypothetical.

Using MRI to track the effects of this drug on the liver is useful because “you can test a treatment over time and track changes in a reliable way,” said Dr. Jason Wright, a radiologist at Radiology Ltd. who is not on the grant application, but did train under Martin. “That’s helpful, and certainly you wouldn’t want to keep biopsying a patient to see if there’s fat in their liver.”

If the team doesn’t win the grant, it will not be deterred, Gomez said.

“My team is going full speed, we truly believe in what we’re doing,” Martin echoed. “This is what I’ve been working on through my professional career and won’t stop with one grant.”