The federal proposal to expand target shooting, hunting and fishing on public lands is drawing attention in Arizona.

In September, U.S. Secretary of the Interior Ryan Zinke directed land managers to come up with a plan to expand recreational shooting in areas like Ironwood Forest National Monument near Tucson. Sitting at 129,000 acres, the monument is open to the public for hunting, fishing, camping, horseback riding and sightseeing. It is currently not open for target shooting.

The monument receives visitors daily in the form of bird watchers, students on field trips and environmentalists exploring the native vegetation.

Supporters say it could mean more hunting and fishing opportunities on federal land. Opponents think it risks people’s safety and could trash some of nature’s most pristine areas.

The potential is huge for Arizona. The federal government owns more than 38 percent of land in the state, or more than 28 million acres, according to Ballotpedia.

The Bureau of Land Management, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and National Park Service are among the agencies charged with coming up with a plan.

Five Arizona residents who hunt or target shoot discussed the proposed expansion and shared their stories.

THE HUNTER

Jensen Thelander has been hunting since he was 10 years old, when his father gave him his first gun.

“It’s second nature,” Thelander said. The 21-year-old hunts a range of game, including coyotes, quail and elk. “There’s no better way to get close with nature and be a part of nature than being outdoors hunting.”

He supports shooting, hunting and fishing on public lands, but said he has experienced difficulty getting access to some of public lands bordered by private property. Thelander said unless a hunter knows the landowner, it is difficult to get through the property or go around it to reach public land.

Hunters in Arizona and other parts of the country have to compete for game by buying hunting tags, with state officials choosing a limited number telling hunters what kind of game they can hunt and how many animals they can kill. Competition for hunting tags for big game like elk and bighorn sheep can be tough and, if there are too many hunters in one area, it makes it difficult for hunters to fulfill their allotment.

Thelander and his friends, Colton Elmer and Sean Deacon, hunt around Arizona and think millennials like themselves enjoy hunting because of its rising presence on social media and new technologies like gun scopes that can see farther and clearer for more precise aim and heat sensing trail cameras that can track animals’ movement throughout the night.

Thelander said hunting weapons and recreational weapons are different. There are different regulations for each. For example, there are military-grade guns that can be used in target shooting but not for hunting animals.

Thelander and his friends said hunters need to follow a code of ethics when hunting. Taking down a majestic animal such as an elk requires a high caliber gun. A small caliber weapon could only injure the animal, causing suffering.

THE ENVIRONMENTALIST

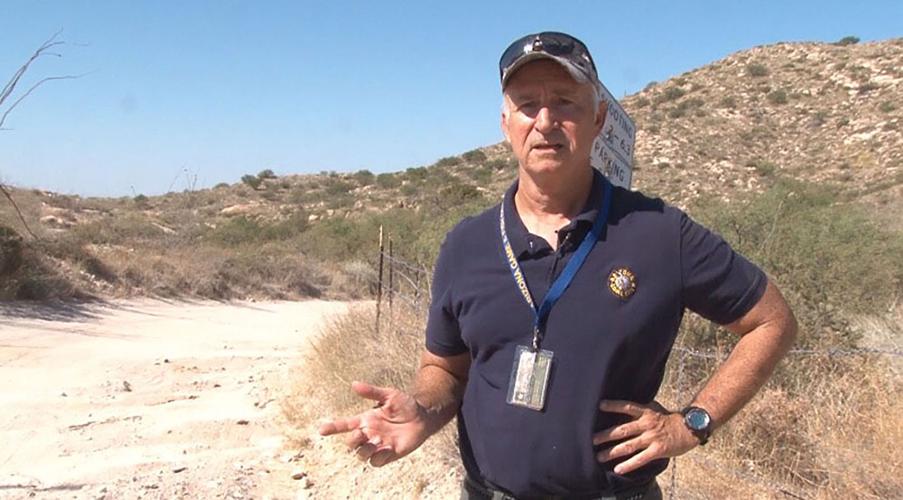

Tom Hannagan, a hunter and president of Friends of Ironwood Forest, a nonprofit group that protects the recreational area’s history and landscape, said expanding target shooting could interfere with hunting, scare away hikers and lead to more damage of hieroglyphics and native vegetation.

Hannagan said recreational shooting hasn’t been an issue due to a resource management plan by the Bureau of Land Management banning recreational shooting on the national monument because of such concerns.

“It would be unfortunate to diminish a lot of other activities for that one activity,” he said.

Hannagan said the Interior Department order is puzzling because it says the point is to open public lands to more uses, but target shooting might impede that.

Hunting is a “stealthy” sport that requires waiting for game to come by and only firing a few shots, he said. Multiple shots fired during target shooting could scare animals away from hunters.

Hannagan said funding cuts for the Ironwood Forest are possible, which would mean less staff to oversee target shooting.

“If you have recreational shooting, it’s going to dissuade people from using the monument for other purposes,” Hannagan said. The sound of shots firing can be frightening and could turn away potential campers and hikers, he said.

Hannagan said people also have damaged native vegetation, rocks and hieroglyphics.

THE INSTRUCTOR

Thomas Wacker said he thinks opening up public lands for recreational shooting is a great idea as long as shooters are “held accountable” for shooting safely and responsibly.

As a hunter and firearms instructor, Wacker said he always uses safety first when using his guns.

“It becomes sort of a ritual,” Wacker said. He said to first treat every firearm as if it were loaded and check that the bolt where the bullets are placed is open and empty. He tests the scope on his gun to make sure it is accurate when he is shooting. And he makes sure that if anyone is with him they are behind the barrel of the gun.

Wacker target practices on public lands such as Redington Pass in the Coronado National Forest. He started hunting when he was 10 years old, hunting pheasants, ducks and quail and has since added bigger game like deer.

THE TARGET SHOOTER

Dr. Richard Weyer, a retired dermatologist, says target shooting helps him recover from back surgery.

“I think recreational shooting is an excellent hobby,” said Weyer, who shoots at the Southeastern Regional Park Shooting range in Tucson. Weyer supports shooting as an activity as long as shooters are following safety guidelines.

Target shooting keeps his mind and body sharp. He will even change up the distance he shoots his targets at depending on how far he wants to walk to bring the paper target back to his station.

He said it also helps with his hand-eye coordination and helps keep himself physically fit. He enjoys recreational shooting as well as occasionally hunting animals such as deer and antelope.

THE OFFICIAL

Mark Hart, spokesman for Tucson’s Arizona Game and Fish Department, said the agency supports the expansion.

“We support the greatest amount of public access to public lands,” Hart said. “But the devil’s in the details. It will be up to those agencies to determine whether or not that’s an appropriate use in those areas,” Hart said.

Hart said shooting ranges are the safest place to practice shooting, but there are public places where people can shoot firearms. Recreational shooting is allowed in Coronado National Forest as long as shooters follow regulations such as not shooting across or toward roads and not shooting native vegetation.

A six-mile area in the national forest is closed to shooting because recreational shooters who used the area left behind trash, Hart said. He said there have been television sets left out that were used as targets as well as empty rounds and other debris.

Hart said the department supports “packing out what you pack in”, and leaving the land in good condition. Hart’s biggest concern with the allowance of more recreational shooting is people leaving behind their trash and leftover bullet casings.

Game and Fish has annual checkpoints to try to keep the land as clean as possible and will continue to do so if recreational shooting is expanded.

“Don’t penalize responsible shooters for irresponsible ones,” Hart said.