Thick mesquite branches almost touch one another as they dangle from Arroyo Chico’s banks. Javelinas regularly cavort through the wash, and hawks and tanagers dart across the treetops.

During big storms, commercial trucks sometimes get stuck so deep in floodwaters near the arroyo that firefighters have to pull them out. Neighboring parking lots and driveways are regularly waterlogged. Mosquitoes breed in standing water in the wash.

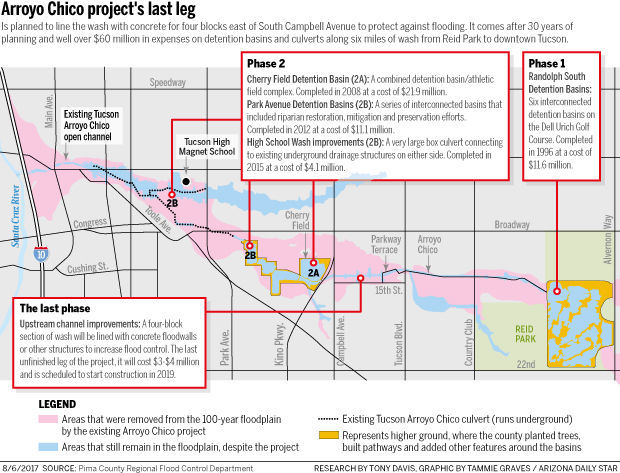

These conflicting images highlight a years-long struggle over the future of four blocks of Arroyo Chico through midtown Tucson. Residents, business leaders and agencies have long grappled over whether to protect this stretch from South Campbell Avenue to East Parkway Terrace, a block west of South Tucson Boulevard, from floods with a multimillion-dollar set of concrete walls and culverts.

It’s the last leg of the arroyo without flood protection work, after three decades of flood-control planning, studies, and land-clearing on the rest. This final project has been planned for years, but delayed due to disputes between government agencies and a lack of funds.

The earlier efforts produced more than $50 million worth of detention basins and culverts aimed at protecting homes and businesses along six miles of wash and tributaries. This year, federal money became available for the last leg.

Sometime next summer, the Army Corps of Engineers expects to issue a contract to build 5-foot-high flood walls along the arroyo from Campbell east to Parkway Terrace. Box culverts will also be built under three streets crossing the wash, to lift them out of floodwaters’ path. Construction will then start and finish in 2019.

Pima County officials will be reluctant participants. “We’re stuck between competing federal agencies,” said Larry Robison, the county’s Arroyo Chico project manager.

A computer model approved by the Federal Emergency Management Agency shows this project isn’t needed. But the Army Corps’ computer model shows it is, so it’s on. The county Regional Flood Control District will provide $700,000 of the project’s expected construction tab of $3 million to $4 million. The Corps will pay the rest.

GREENBELT AT STAKE

This wash section is the western edge of a greenbelt, leading east to Reid Park. Besides mesquites, non-native tamarisks and native willows adorn the arroyo as it slices through upscale and middle-class neighborhoods south of East Broadway.

Construction of flood walls would take out many of the arroyo’s trees.

Originally, the entire greenbelt was slated to be lined with concrete. Neighbors fought back and won preservation for all of the wash and its vegetation, except along this last leg. Then-City-Councilwoman Molly McKasson and County Supervisor Dan Eckstrom also pushed for preserving the wash from Reid Park to Parkway Terrace. Authorities instead built a series of large detention basins at the park and west of Campbell.

“The arroyo is an amenity. A wildlife corridor. It brings down the temperature. It’s one of the reasons a lot of people live there,” said Richard Roati, a longtime resident of the Broadmoor-Broadway Village neighborhood, which straddles the arroyo east of Tucson Boulevard. “We used to pay flood insurance in the neighborhood because the arroyo would flood. They put in basins in Reid Park and west of Kino and the need for flood insurance was eliminated. The work is done, in our minds.”

The new project is also opposed by their city councilman, Steve Kozachik, whose Ward 6’s west boundary is Tucson Boulevard. The office of Councilman Richard Fimbres, whose ward contains the new project area, didn’t respond to requests for comment on the project.

“A lot of neighbors have put sweat equity into maintaining the wash. If the feds have plenty of money they want to spend on flood mitigation, I have plenty of other areas around midtown where it’s needed,” Kozachik said.

For resident Nanci Nelson, the stakes are visible from her backyard, overlooking the wash along Parkway Terrace. She sees native wildlife there virtually every day: javelinas, coatis, coyotes, skunks and badgers. She photographed five javelinas in the wash recently.

“Harris hawks like to hang out there,” Nelson says, pointing to tall trees on the south bank. “Other hawks hang out here in the wash — it’s where they get their breakfast, other birds, mainly. There’s finches and blackbirds, and I’ve had cardinals out here for 10 years.

“It’s a spiritual, magical place. There’s not many places in central Tucson like this. But I’m frustrated and I’m worried. Our wildlife should be protected, not destroyed.”

Flooding problems

Bud and Shirley Dail, who own Shirley’s Plans along South Plumer Avenue, are frustrated that nothing has been done in that area. Bud Dail said he’s concerned about mosquitoes that frequent the wash when water ponds up during storms.

While mosquitoes never get into their office building, they invade the parking lot, bothering customers, said Dail, whose business compiles various construction plans for contractors interested in making bids on them.

“We’re constantly calling the city and county to come out and do something about it,” he said. “Every summer during the monsoons, we get mosquitoes.”

During a big storm in mid-July, an employee’s car got stuck in the business’s parking lot when floodwaters came into it. Water pouring over their driveway from Plumer, 8 to 12 inches deep, also made it hard for other vehicles to get in and out, he said.

Samuel Argomaniz, who works for another company in the same building, tells similar stories. Every time it rains heavily there, at least a foot deep of water flows from the wash into the parking lot, he said. Many times, the lot is flooded enough that cars can’t get through to the parking, said Argomaniz, office manager of Keystone Masonry LLC and a supporter of this last section of the flood-control project.

Kevin Dail, Bud’s son and the business’s office manager, and Amy Adolph, owner of a neighboring company, recall bigger flooding problems. Ten or so years ago, a fire official ordered his crew to pull a truck out of a flooded Plumer Avenue after the truck driver had refused the offer of help, Dail said.

Adolph, an owner of B&R Refrigeration on South Plumer, photographed a similar scene on that street a year ago this week. Every time it rains heavily, her employees have to move their cars out of floodwaters’ path. But she said she needs more information about the project before taking a stand.

Neighboring business owners Joe Wainwright and Pete Raguzin are opposed.

“It gets flooded out, enough water flows through that you shouldn’t drive through five or seven times a year maybe,” said Wainwright, owner of Wainwright’s Locksmiths at East 15th Street and South Olson Avenue. “There’s no reason people can’t drive a block or two down the road. It’s a minor inconvenience.”

Raguzin, owner of Spray Master Auto Body and Paint Shop a block west of Wainwright’s, said he’s concerned that the project’s construction work will snarl local traffic, particularly if the funds are cut midway through the work. He said he’s never seen flooding near his business. Officials backing this project “are looking for something to make their employment worthwhile,” he said.

INSURANCE ISSUES

This final leg’s problems started in 2013, when Nanci Nelson went to the county, raising concerns about potential habitat damage and about the possibility that building the project could unearth radioactive tritium from the wash. That’s because the long-vanished American Atomics plant on Plumer Avenue near her house had numerous tritium gas leaks that led to its forced shutdown back in 1979.

Pima County officials wrote the Army Corps, asking that the project be canceled. The Corps had a contract in hand to start building but chose to terminate it to explore these concerns.

Ultimately, studies found no more tritium in the wash than would occur naturally. A Corps-financed study from this year, however, found nine soil samples from the wash contain toxic chemical compounds known as polyaromatic hydrocarbons at levels well in excess of state standards for exposure to residents.

Those soils must be dug up and taken to an approved hazardous waste disposal site before construction begins. Typically, the compounds are produced from the incomplete burning of coal, oil and gas, garbage, or other substances like tobacco or charbroiled meat, the federal government says.

Then, the project was delayed by major disagreements over whether it’s needed. In correspondence with the Corps, the county asserted that the completed Arroyo Chico work had made this last stretch unnecessary. Only a very small section of land along the wash remained vulnerable to flooding, including short stretches of the roadway crossing the wash, county officials said.

Their view was based on a computer model approved by the Federal Emergency Management Agency that FEMA used to rewrite floodplain maps there. County officials estimated the previous work removed well over 1,000 homes and businesses worth $226 million from the 100-year floodplain and that number will eventually top 1,300. Those landowners, including some in this contested section, no longer must buy flood insurance.

The Corps stuck by its computer models showing the flood risk remains in this section and downstream. This last leg is “critical,” Corps officials said. If the project isn’t done, the new FEMA-approved floodplain map may have to be withdrawn, putting many properties back into the floodplain, the Corps said.

The FEMA model doesn’t meet the Corps’ standards, which are developed by engineering experts and “arduously reviewed,” Corps spokesman Dave Palmer said.

If the FEMA map is withdrawn, the county may not be able to get federal disaster aid for people living and working near that stretch of the wash after a big flood, wrote Suzanne Shields, the county flood district director, in an October 2016 memo.

Another reason county officials are cooperating on the project is that they’re concerned if they don’t, they’ll have trouble getting federal money for future projects they want.

“There’s an inherent risk in not working cooperatively,” said Eric Shepp, the county flood district’s assistant director.

County officials say they hope to persuade the Corps to replace concrete walls with more environmentally friendly material such as riprap, or rocks typically used to armor streambeds, bridge supports and shorelines against storm damage.

The Corps is evaluating this and other county requests for a toned-down project, spokesman Palmer said, as the project goes through a final redesign before construction starts.