The first railroad in Jerome, a premier Arizona copper mining town with billion dollar views, was the United Verde and Pacific Railway chartered on March 20, 1894.

The premise behind its inception was a drop in copper prices three years earlier.

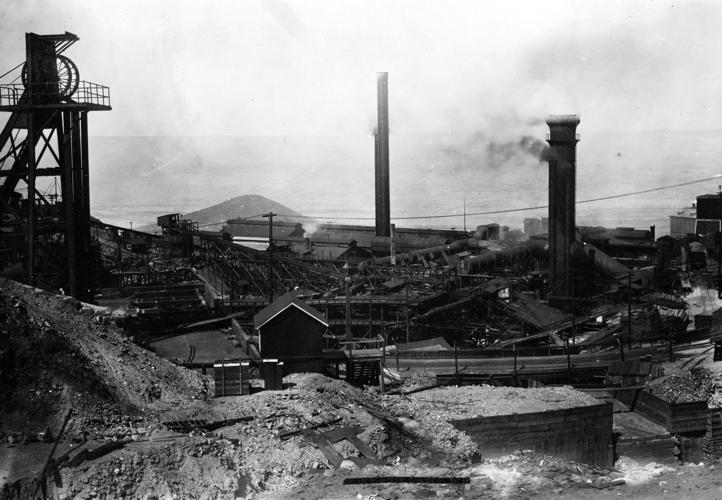

High transportation costs by wagon proved challenging to the local mines (most notably the United Verde Mine) in the Black Hills comprising Cleopatra Hill, Mingus and Woodchute Mountains.

The benefits of rail transport proved enticing as a means of heightening greater production at the mines, increasing employment and bolstering the local economy through supplying Jerome’s residents with provisions along with supplies for the local mines and smelter.

The UV&P railroad was built and owned by copper magnate William Andrews Clark, who operated major copper producing mines in Butte, Montana and the United Verde Mine at Jerome. Clark was also president of the United Verde Copper Co.

The railroad that traveled around 7,834-foot Woodchute Mountain had 186 curves cut through extensive limestone beds and shaly mudstone and was known as the “crookedness line in the world.”

It was built higher to avoid steep canyons, with the exception of Horseshoe Canyon, by a trestle bridge.

The line was built to accommodate twenty-six miles from the connection with the standard gauge Santa Fe, Prescott and Phoenix Railroad at Jerome Junction at 4,616 feet in Chino Valley to the United Verde smelter at 5,600 feet on the slope of Mingus Mountain and on to Cleopatra Hill above the town of Jerome with a maximum gradient of three percent in both directions from the summit on Woodchute Mountain.

The maximum height of the track reached 5,939 feet called First View since this was the first view of the Verde Valley and river below for eastbound passengers to Jerome on the railroad.

It was built to a gauge of three feet. The narrow gauge railroad was an attractive less-expensive railroad to build in contrast to the larger standard gauge railroad whose rails are spaced 4-feet, 8-and-a-half inches apart. This was especially the case in rugged and remote terrain.

The smaller distance between rails enabled less dirt and rock to be moved during construction. The size of cuts and tunnels were necessarily reduced for additional cost savings. Less steel and wood were needed for both rails and ties along with its optimal usage of smaller locomotives and cars.

The only additional costs were incurred at Jerome Junction, where freight was transferred between narrow gauge and standard gauge. Copper Matte from the Jerome smelter was transferred from the UV&P for shipment by the S.F.P.& P while in exchange coke and coal were transferred to the narrow gauge cars by bin on route to fuel the smelter.

Notable events during its 25 years of operation included participating in the deportation of Jerome’s striking miners in 1917 and several derailments due to heavy rains, a broken wheel flange and a missing role stabilizer.

Challenges from a 20-year fire burning underground since 1894 and issues involving cave-ins and lack of adequate timber support, coupled with new processing techniques to process low grade ore, supported the implementation of open-pit mining operations.

A new smelter was erected in 1915 five miles northeast of Jerome at Clarkdale in the Verde Valley, with the new Verde Valley Railroad of the Santa Fe serving its needs.

A redundant UV&P railroad was no longer necessary or cost effective.

The standard-gauge Verde Tunnel and Smelter Railroad did its part of transferring ore from the mine site through the 7,200 foot long Hopewell Tunnel to the Clarkdale smelter. Postwar economic conditions negatively affected the copper market.

These combined situations necessitated the closure and dismantlement of the Jerome smelter. The UV&P continued to operate until 1920.

Jerome Junction was renamed Chino Valley in 1923 and the Santa Fe continued service at the stop until the 1970s.

Last vestiges of the UV&P that remain visible today are found in an automobile road around Woodchute Mountain through Horseshoe Canyon.

An aerial view of its route also exits as a barren scar cutting along the alluvial slopes in Chino Valley.