The Charleston Mine, located eight miles southwest of Tombstone, produced lead and zinc along with byproduct metals: gold, silver and copper.

The name of the mine was derived from the nearby historic milling town that serviced the Tombstone mines during the 1880s. The Charleston claims themselves were located in 1928.

Early estimates surmised the size of the zone of mineralization to be a minimum of 2 miles long and three-quarters of a mile wide.

Attempts to mine lead and zinc ores in the 1930s proved unsuccessful except for a few thousand tons.

It was not until Charles H. Suiter acquired the property that production of lead and zinc concentrates was achieved through the use of a crude mill. Diamond drilling in the early 1950s was carried out by lessees and the Ryan Oil Co.

The mine tailings proved attractive, as they contained excellent specimens of rosin jack, a yellow variety of the zinc ore sphalerite.

Country rock at the mine site includes andesite and rhyolite, part of a series of volcanic flows over 20 million years ago, some of which were altered by intense hydrothermal action forming sericite, a gangue material at the mine site.

Sericite, a hydrous mica material, is a powdery substance used in rubber, ceramics, agriculture and paints.

The sericite mined at Charleston was described as a product finer than flour. It was sold to the Tombstone Flotation Mill beginning at $10 per ton.

The sericite crude ore was washed prior to the processing of the sulfides by flotation. This clay-like material, containing microscopic grains of mica, was purchased by the White Eagle Stucco Corp. in Phoenix. The mica was used in the manufacture of high-quality cement finish used to provide opaque whiteness in the swimming pool industry.

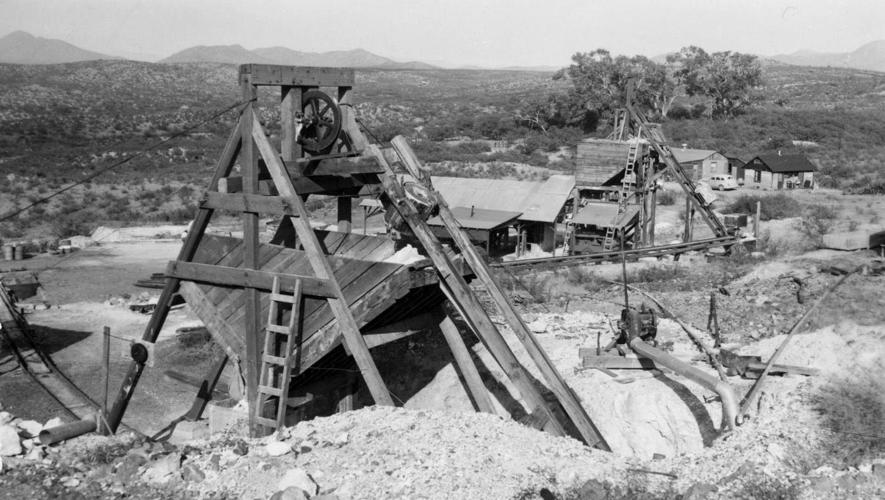

The mine was first worked by underground methods. But rising costs combined with the soft, slippery nature of the sericite in underground workings resulted in the need for reinforced timbers because of caving concerns.

By 1955, the mine consisted of six shafts, the deepest being 104 feet on a 55-degree incline, resulting in multiple levels comprising several hundred feet.

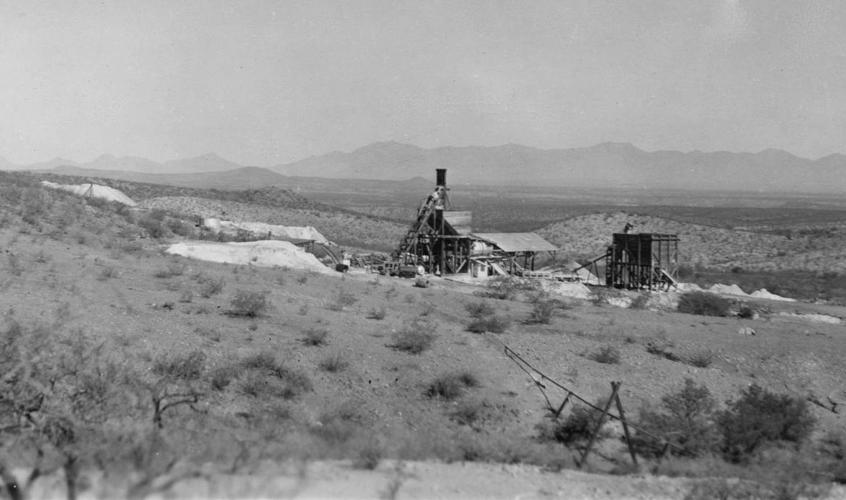

Open-pit operations followed, carried out by the James Stewart Construction Co., which removed 60,000 tons of overburden to further mine sericite. The sericite was sold to the Western Chemical Co. and the Dutch Boy Paints Co., while the metal concentrates were sold to the International smelter at Toole, Utah.

By the late 1950s, the mine had produced $40,000 in profit.

The pit reached a size of 50 feet deep, 500 feet long and 150 feet wide.

Suiter likened the association of sericite to copper on a similar mining property to one in Butte, Montana, regarding the sale of his mining corporation in the early 1970s.

The James Stewart Co. was the owner in 1984, and the mine was reported to have long since been abandoned in the early 1990s, with a deteriorating mill and surplus of scattered core samples.

The mine is on a mixture of Bureau of Land Management and State Trust land.

Harlow L. Jones, who owned seven of the mine’s patented claims with plans to initiate further sericite and metals production, supported later reclamation attempts involving the BLM and the Arizona State Mine Inspector’s Office at the site, consisting of 5 acres of waste dumps and mine entrances.

Sulphides naturally leaching from the tailings and pit caused acid rock drainage after rains, with water levels reaching a depth of 7 feet in the confines of the pit.

By the early 2000s, the pit was partially backfilled with mine tailings and cement mill foundations, with plans in place to incorporate an impermeable layer to prevent water runoff that might affect the nearby Upper San Pedro River watershed. The $250,000 remediation attempt was never completely fulfilled, due to the issuance of a mineral exploration permit on the State Trust Land property.