It was December 1983 when Frank O. Sotomayor, a Tucson native working at the Los Angeles Times, went to see the newspaper’s editor, along with two newsroom colleagues. They had previously met twice with the editor with a major request but were denied both times.

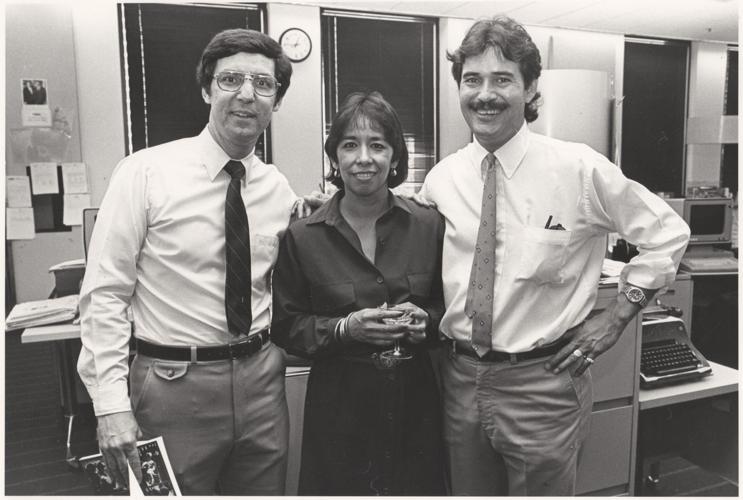

The three, including columnist Frank del Olmo and reporter George Ramos, would not be denied this time.

While this is a story about journalism, it’s more than that. It’s about the contributions in everyday life made by Latinos and the historic challenges Latinos have and continue to face. This is a story about doing what’s right against the odds and the pushback by the privileged status quo.

The three had been part of a groundbreaking reporting project that the Times — one of the top five newspapers in the country — had ever conducted at the time. In a 27-part series, 17 L.A. Times journalists and photographers had produced a sweeping examination of Latinos in the Los Angeles metro area.

Sotomayor, who was raised in Barrio Hollywood and is a graduate of the University of Arizona, was one of three team members with strong Tucson roots and connections. The others were José Galvez, who was born and raised in Barrio El Hoyo and was a photographer for the Arizona Daily Star before becoming the first Chicano photographer at the Times; and Virginia Escalante, an Eloy native who spent her summers harvesting crops in California and is a UA graduate. A fourth reporter, Louis Sahagun, worked for several years at the former Tucson Citizen before joining the L.A. Times.

Sotomayor, who was co-editor of the project and who is now retired and living in Tucson, has laid out the story in “The Pulitzer Long Shot: How Our 1983 Latino Stories for L.A. Times Won Journalism’s Top Prize” (http://jourviz.com/long-shot/index.html). He documents how a small group of journalists, all Mexican-American, stunning the elite world of journalism, gave birth, developed and pushed through the historic project, which earned the Pulitzers’ most honored recognition for Public Service in 1984. It was the first Pulitzer awarded to Chicano journalists.

“To me the series underscored the value of in-depth news coverage of underreported communities,” Sotomayor wrote in his account. “Until publication of our series, such coverage had often been undervalued and derided as ‘the taco beat.’ Our series signaled to the journalism world the rich value of explanatory journalism about all the people in our communities.”

“Latinos” was a massive, unprecedented in-depth exploration of a significant portion of Los Angeles’ population, which historically had been ignored, at best, or at worst stereotyped and maligned in the newspaper’s coverage by white male journalists. The landmark series, and a subsequent book containing all the stories and a trove of photographs, was welcomed by a large share of Angelinos, and lauded by journalists and community leaders outside of Southern California.

However, when the Los Angeles Times’ editors submitted 27 nominations to the Pulitzer Prize committee that year, “Latinos” was not included. The Times’ editor said the project was good but “not the type that wins a Pulitzer.” Even within the Times’ newsroom, some fellow journalists were hostile and resentful of their Chicano colleagues.

“All of us on the team placed enormous pressure on ourselves to produce journalism that was not only good but extraordinary. We regularly worked six days a week and sometimes seven. We all felt the strain and made personal sacrifices,” wrote Sotomayor.

In Sotomayor’s publication, Escalante recalled, “The pressure was heavy, intense, and the atmosphere in the newsroom felt as if the rest of the staff expected us to fail.” They were subjected to racist and other insults through much of 1983 when the team conducted more than 1,000 interviews and wrote their stories.

After the third meeting on Dec. 30, the Times’ editor gave Sotomayor, Ramos and del Olmo the green light to submit their project to the Pulitzer committee. The three crammed into an office, wrote the nomination letter, selected 10 stories and the book and several days later sent the nomination to Columbia University in New York.

One of the legacies of the series and the 17 journalists is that daily journalism began to examine its failings in covering communities that had been excluded from balanced and in-depth reporting. Newsrooms, which had been the domain of white males, were slowly opening their doors to ethnic minorities and women. As diversity slowly grew in the newsrooms, so did stories examining the wider and deeper breadth of Latinos across the country.

Galvez, who left the Times in 1992, is now living in North Carolina, from where he photo-documents Latinos in the Southeast and on the Eastern Seaboard. He observed that his local newspaper has focused more attention on Latinos. Still, there remains a wide gap in local coverage, he wrote in an email.

“I do think the mainstream media has lost focus on covering the communities in this day of Trump ... that they’re all too often not reporting on the everyday issues like we did with the project,” wrote Galvez.

Several of the project’s members remain in daily journalism. Several, including del Olmo and Ramos, both of whom were major voices in Los Angeles, have passed away. Others went into academia.

The legacy of the 17 journalists is cemented in American journalism history. But their efforts and that of the many Latino journalists who have followed have not ended.

There is more to do.