This time I knocked on his door. I.K. Bruto, who usually calls me, wasn’t surprised that I was standing outside his west-side house.

“I know why you’re here,” said my long-time imaginary friend. “You’re leaving the newspaper.”

Yup. Let’s have coffee and talk, I said as I stepped inside.

I knew, of course, my work at the Arizona Daily Star would end some day. I just didn’t know when. But the day arrived Friday after I had accepted in April an early retirement offer from the corporate office in Iowa.

As a Santana tune riffed in another room, Bruto filled up the two Tucson-centric coffee mugs, one with the old bright red Jácome’s logo and the other from Poblano Hot Sauce. He said: “Nineteen years is a good number. I betcha you didn’t think you’d last that long writing columns about Tucson, did you?”

Nope, I said in a melancholy voice.

The shrine known as El Tiradito in Barrio Viejo is a where people light candles and leave notes in the hope that their prayers may be answered.

I didn’t know what to expect in 2000 when I began writing columns for my hometown newspaper which — as a point of pride — I delivered as a kid on the west side around St. Mary’s Hospital.

Column writing was a new step in my journalism career, which began in 1981 as a reporter here in La Tusa, and continued in Massachusetts and San Diego before coming full circle. It’s been quite a ride.

In those 38 years, what I wanted to do was to tell people’s stories, about their lives, dreams, successes and fears. But when I returned home invigorated with a new mission, I wanted to share the histories of Tucson families, whether they had been here for generations or whether they were recent arrivals. I wanted to celebrate immigrants, regardless of their legal status, by sharing their stories of perseverance, hard work, dedication and heartbreak.

As a son of a proud Tucsonense mother and an equally proud father from Chihuahua, Mexico, both of whom filled me with a love for Tucson, and husband to Linda Portillo, my Tucson-born wife whose family has deep Sonoran roots, I had a deep and wide understanding of Tucson and our border region. This gave me entry to people’s homes and lives. People and families entrusted with me their stories and words.

“Dude, a lotta people appreciated your stories about Tucson’s culture and history, and its music and barrios,” Bruto said. “And let’s not forget your columns about — can I say the ‘G’ word? — gentrification,” he said over the sorrowful words of Lalo Guerrero’s “Barrio Viejo,” a song by the Tucson-born singer who lamented the loss of his beloved downtown barrio.

Bruto and I spent a lot of time talking, sometimes tersely, about Tucson’s gentrification, especially how it is affecting and changing our historic barrios. He was usually blunt. He didn’t hesitate to let me know when I was wrong. Bruto first appeared in a column in May 2006. He disappeared but charged back two years ago.

Others, real people, have also appeared and reappeared in my columns.

In 2000, I wrote about Marta Ureña and her three children who almost lost a Habitat for Humanity home that she and her husband had been working to build. Her husband, Alberto, a U.S. citizen, had died of a heart attack before the house was finished. Ureña stood to lose the house because she was undocumented and could not legally work to pay the mortgage. But an anonymous donor interceded and paid the $60,000 mortgage.

In 2000, Ernesto Portillo Jr. wrote about Marta Ureña and her three children who almost lost their Habitat for Humanity home after her husband died. An anonymous donor interceded and paid the $60,000 mortgage.

Then in early 2015, I revisited the Ureña family who were still living in their Habitat home near Sentinel Peak. The eldest, Ana Ureña, was set to graduate from the University and Arizona and her mother was expecting her legal residency card later that year. The donor, whose identity was still a secret to the family, gave the family the stability for Ureña and her children to fulfill their dreams and goals.

“You can’t leave,” Bruto said loudly. “You gotta keep writing.”

I chuckled. He was channeling my mother. I told my alter-ego to chill on the drama. I’m not indispensable, I told him.

“OK, you’re right. We really don’t need you,” he said with a snark but then he got serious. “But what we do need are more voices in the media reflecting the barrios, Tucson’s growing diverse communities, the young and old. We need more insightful stories of Tucson’s history and culture to understand where we came from and where we’re going.”

Bruto was winding up and it wasn’t the caffeine. It’s his normal state.

“More now than ever, in these trying times, we need more people publicly speaking out and loud. The immigrant communities are under assault. Children are being separated from their families and being detained in concentration camps. Yes, I said it: concentration camps,” Bruto growled, stretching out his final words.

There will be others, I responded. On any given day a spark will fire up a young Latinx Tucsonan. I remember when I had my moment, I said to Bruto.

It was the early ’80s, I was studying at the UA and working at my dad’s Spanish-language radio station, KXEW, a critical source of information for the Latino community. The station and La Frontera mental health clinic, then a small store-front operation in South Tucson on South Sixth Avenue, held a radiothon to raise money to build a new facility on the site of an old unused stockyard on West 29th Street and the freeway.

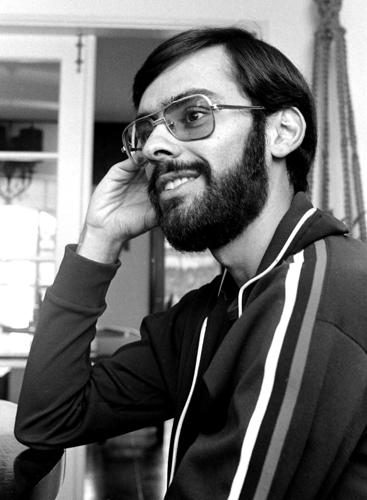

University of Arizona graduate Ernesto Portillo Jr. in 1980, as a volunteer with Los Amigos de las Americas.

Gobs of people came to support the bilingual clinic. It was a huge family event. There was music, speeches and a stream of gente who walked up on the stage and donated whatever money they could. I’ll always remember the little nana who took a coin purse out from under her bra strap and emptied it into the collection container.

It was beautiful, an uplifting coming together of Tucson’s Chicano and Mexican immigrant communities. And there was not a single word in either the Arizona Daily Star or Tucson Citizen.

I got angry. I wrote a letter to the Daily Star criticizing its lack of coverage and respect for Tucson’s Mexican-American community. I complained of the lack of a wider picture of Tucson.

I’ve carried this with me for more than 40 years.

“You did what you set out to do,” Bruto said with a hint of sadness. But then perking up he added: “Let’s go do something else. Let’s get outta here and do some desmadre and have fun doing it.”

You’re on.

A faint rainbow appears over downtown Tucson and the city after monsoon storms on July 24, 2017.