I can’t remember exactly when I met her. Before meeting her I had seen her around, usually dressed in her flowing blue-green dress with sparkly dots. Every time, her eyes were closed, hands clasped and her head was covered.

When I finally met her, I was in the fourth, maybe fifth grade at the old All Saints Catholic School. I was in a play with her. I probably was dressed in white cotton pants and a plain white shirt. Oh, and I wore sandals, more than likely the Mexican kind with retread soles from a Goodyear or Uniroyal tire. Definitely it wasn’t the sixth grade or, heaven forbid, the seventh grade because I was too cool by then to be dressed like a Mexican campesino.

But there I was kneeling at the altar at St. Augustine Cathedral, holding some flowers in a sarape draped over my shoulders, and there she was, standing in her long outfit. That was my first formal introduction to the Virgin of Guadalupe.

The Virgin of Guadalupe is said to have appeared to Juan Diego in 1531 on Tepeyac Hill outside of Tenochtitlán. Over the years, she has taken on a multitude of meanings.

Wednesday, Dec. 12, is her feast day. The night before, millions of Catholics across Tucson, Mexico, Latin America, the United States, and the globe, will pray to her and for her; they’ll sing to her; they’ll walk on their knees toward her at her Mexico City shrine; they will petition her for her intercession; they will thank her for the blessings that they attribute to her; or they simply will stand or sit in her presence basking in the warmth of their faith during the midnight vigils at churches and homes.

She has that kind of powerful pull. And she’s had that universal appeal for hundreds of years.

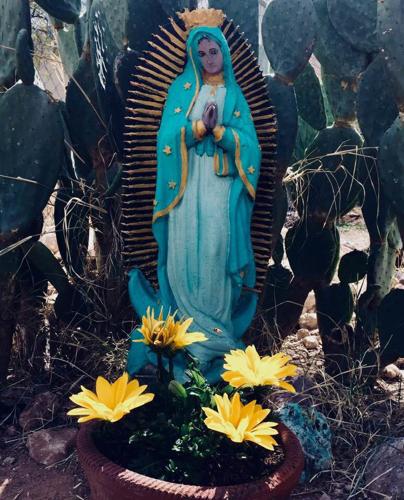

A shrine to the Virgin of Guadalupe at Casa Maria, a soup kitchen in Tucson.

While I don’t consider myself a devout religious follower of La Virgen de Guadalupe, I don’t discount her meaningful role in the lives of those who venerate her. Rather, I am a curious follower of the dark-skinned Mexican Madonna. She fascinates me as a cultural icon in the Chicano and wider Latino community. I admire her ability to unite people.

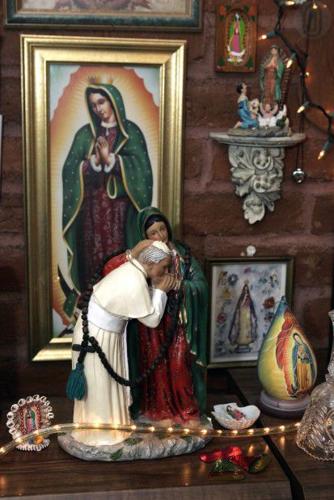

For me, as a writer for nearly 20 years with the Arizona Daily Star, La Virgen is one of my top subjects. According to the Star’s archives, the first time I included her name in a column was several months after I had started writing for the paper in 2000. Since then I have written about artists who paint her, families who collect her images, individuals who have turned to her in a time of trouble or need. I wrote about a Tumacácori family who lost their home and collection of Guadalupe art in a fire on Guadalupe’s feast day and a Cubana who crossed the border to seek political asylum on that special day.

Students Isnira Vega, 15, and Desiree Sanchez, 14, carried an image of the Virgin of Guadalupe while walking in a Labor Day Parade around Reid Park in 2002.

Mostly I’ve included her in stories about her symbolism and her meaning.

The Virgin Mary is said to have appeared several times to an indigenous Juan Diego on Tepeyac Hill outside of Tenochtitlán (now Mexico City) in 1531, 10 years after the Spanish vanquished the Aztec inhabitants. Her story and symbolism became a powerful tool that the Spanish used to entrench their rule and spread Christianity. But over the years Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe has taken on a multitude of meanings.

Murals on A’s Barber Shop, 902 N. Grande Ave. “My grandmother loved it,” says Arthur “A.J.” Navallez, the shop’s owner.

She is a feminist. She protects the poor and defends the marginalized. She is an agent of political change. She’s a secular talisman. She’s used to make money. She is the patroness of Mexico and the Americas, including the United States of America. She’s a writer’s muse. She is a rebel.

When Mexico sought its independence from Spain in 1810, her image was at the forefront of Padre Miguel Hidalgo’s peasant army. When farm leader Cesar Chavez led striking farm workers in California in the 1970s, they carried her banner. Surely today a Central American migrant who is making the dangerous journey north through Mexico to seek asylum in the U.S. is carrying an image of la Virgen de Guadalupe and praying for her to intercede, promising her to make a manda, a pilgrimage.

A picture of the Virgin of Guadalupe is wedged into the bark of a tree at the site of a shrine along a migrant trail that passes by Chapman tank near Arivaca.

And thousands of her believers make that pilgrimage, whether it’s walking from Tucson to Mission San Xavier del Bac or traveling to her shrine, the Basilica de Guadalupe in Mexico City. There, Saint Juan Diego’s tilma, which carries on it the seared image of the Virgin, is on display.

Her Tucson connection is as old as the 1775 Spanish colonial presidio. In the early 1800s, a bronze bell hung outside the small adobe chapel of the Presidio Real de San Agustín del Tucsón. The bell was dedicated to the Virgin of Guadalupe and two years ago was brought out of storage at St. Augustine Cathedral.

Lourdes Reyes looks over a Virgin of Guadalupe statue on display at the newly opened Bashas’ Food City at 2950 S. 6th Ave. in South Tucson on Nov. 29, 2000. Reyes, who lives near the new store, bought the statue she is looking at.

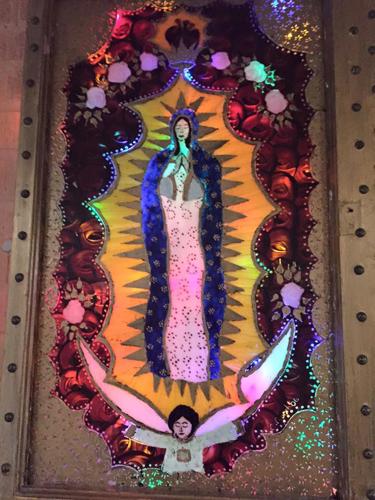

La Virgen will continue to appear to me, whenever and wherever. She’ll show up on a wall, on the hood of a tricked out low-rider car, in barrio art and museum art, on a T-shirt, on a political placard, in a children’s book or in some place far away from her Mexican birthplace.

La Virgen is for the ages.