Nearly 200 residents of Ocotillo Apartments and Hotel on Tucson’s south side were faced with an option Wednesday morning: pack up all their belongings and leave their only source of housing, or resist property management’s attempts to evict them.

The residents are part of what was supposed to be a sober living community at 1025 E. Benson Highway called “Happy Times.” About a month ago, the program stopped paying the hotel for the residents to live there, according to Ocotillo’s general manager.

The formerly homeless residents were left to fend for themselves, while the business was left with unsettled bills.

Residents said they were promised a sober living community but were left without any of the healthcare, money or food promised to them. Tucson officials said they’ve counted 189 people who will be left without shelter.

The owners of the property posted final notices on residents’ doors Tuesday that “Happy Times has continued to no longer pay for your hotel stay” and residents had until 11 a.m. Wednesday to “leave promptly,” the note said.

Leonard Carrillo Jr. has been living at the Ocotillo Hotel for nearly three months. He used to stay at Santa Rita Park, where he said he was attacked and lost most of his teeth. Someone approached him with the promise of housing, a daily stipend, food and sober living services. But not long after he moved in, the Happy Times program left him, and the other residents, without any of those services.

“This is our safe haven. They’re gonna kick us out, and then we’re all gonna be out on the street, it’s dangerous. It’s really not right what they’re doing,” Carrillo Jr. said.

Most of the residents have a similar story: They were living on the streets when someone from Happy Times approached them with the promise of housing. The only catch: They had to sign up for the American Indian Health Program through the state’s Medicaid provider, the Arizona Health Care Cost Containment System.

The predatory practice is not new to Arizona. The state, and city of Tucson, have recently moved to crack down on the common practice where individuals promise shelter to vulnerable Native American populations and bill Medicaid for services that aren’t provided.

“Credible evidence has been established that individuals were targeted and aggressively recruited with false promises of food, treatment, and housing, only to be taken to facilities where providers billed for services that were not provided,” AHCCCS wrote in a June statement after stopping payments to more than 100 healthcare providers sending invoices for nonexistent treatments.

The Medicaid system’s care management team has worked with residents at the hotel and said the “situation demonstrates the lengths bad actors will go to exploit the state’s Medicaid program, defraud taxpayers, and endanger our communities,” said AHCCCS Communication Administrator Heidi Capriotti. AHCCCS has suspended more than 300 providers to date on allegations of credible fraud, Capriotti said.

While Carrillo Jr. has Native American ancestry, another resident, Ronald Reno, said he was told to lie on the AHCCCS application and say he’s of Native descent.

“I was homeless. And they said, just come stay here, it’s free. We’re gonna give you money for whatever you need, as long as I switch my insurance to Native American insurance,” Reno said. “I said, ‘I’m not native.’ He says, ‘That doesn’t matter,’ and he’s like, ‘Just come in, and I’ll do it.’”

Reno’s girlfriend, Carrie, said the individuals who approached them, “sat us down, made us dial the phone number and we had a piece of paper we had to read to people.”

Reno said he was promised a weekly allowance and would be provided help to get sober. He says he never received money or drug addiction treatment.

“They didn’t give us a fighting chance to get sober,” he said. “They gave us every tool to fail. They gave you a place where you can hide to do your drugs.”

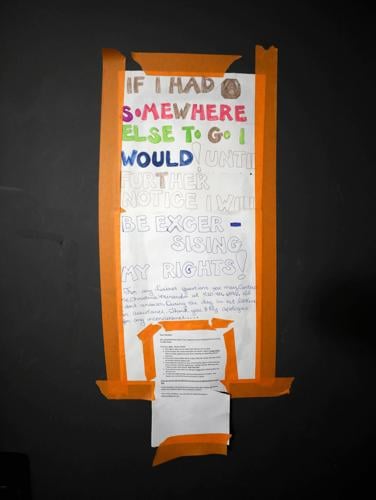

The Tucson Tenants Union and other homelessness advocacy groups went door-to-door Wednesday to alert residents of their rights to not be evicted without a court order.

“A lot of people were self-evicting. And by that, I mean, they were being intimidated, they were being illegally locked out already by management,” Tucson Tenants Union member Nicholas Bruno said.

While some residents took the union’s guidance to stay in their rooms without opening the door for management and await a court order, others decided to leave. Reno packed his belongings on a makeshift trailer of wagons hitched to his bike and said he’s going “out to the desert.”

Reno and his girlfriend have a service dog, and most shelters they’ve contacted said they won’t allow pets.

The city negotiated with the Ocotillo’s owners to delay the evictions until Wednesday after management previously attempted to vacate residents last week, according to Mari Vasquez, the Multi-Agency Resource Coordinator for Tucson and Pima County.

Several city, county, tribal and community organizations gathered around the hotel in the early morning hours to offer services to evictees. But many tenants said they’ve been offered housing through temporary shelter before and had negative experiences.

About 80 people accepted the city’s offer for “some form of assistance or alternate shelter,” said Andy Squire, a city spokesman.

Management said it gave residents “more than a week” to vacate and that “the rooms aren’t even under their names. It’s under the agency.” Residents can pay the nightly rate of $50 to stay at the hotel.

“It was going well for a while … (Happy Time’s) motto was to help people that are chronically homeless, which I did for many years, and I have a soft spot for that,” the general manager said. “And then they stopped paying. And unfortunately, we’re not a nonprofit. We can’t keep people here for free.”

A California-based commercial design firm, Long Beach Designers, has begun the process to request Tucson rezone the location and turn it into multifamily housing, according to city property records.

But as Reno vacates his room to set up shelter in an unknown place, he’s returning to a life of homelessness he’s experienced for a year before moving into the hotel. Although the Happy Times program promised him help for his drug addiction, Reno feels he’s worse off entering the streets again.

“If it’s sober living, I’d rather go to that place to get sober, not worse. I’m worse,” he said.

Get your morning recap of today's local news and read the full stories here: tucne.ws/morning.