When Brendan Bond first started working with the Tucson Police Department’s deflection program in 2018, he said about one in 10 individuals he offered substance misuse treatment to accepted it. Now, it has dropped to about one in 30 people who take up the offer for treatment instead of arrest.

Eli Joy, right, talks with his co-worker, Jose Medina, in the “quiet room” at the CODAC at 380, Medication Assisted Treatment center on Oct. 26. Joy and Medina are peer support specialists and help people through the intake process and talk to others out in the field about getting sober. Pima County and the city of Tucson plan to partner together to tackle the fentanyl crisis while declaring it a public health crisis.

Bond, a peer support specialist with the addiction treatment center CODAC Health, Recovery & Wellness Inc., was addicted to opioids for 10 years. Now, with nine years of sobriety under his belt, he reaches out to vulnerable users of a drug that has proliferated the Tucson metro region: fentanyl.

“I’m having a lot harder time talking to people into going (to treatment) or even trying or even listening sometimes,” Bond said.

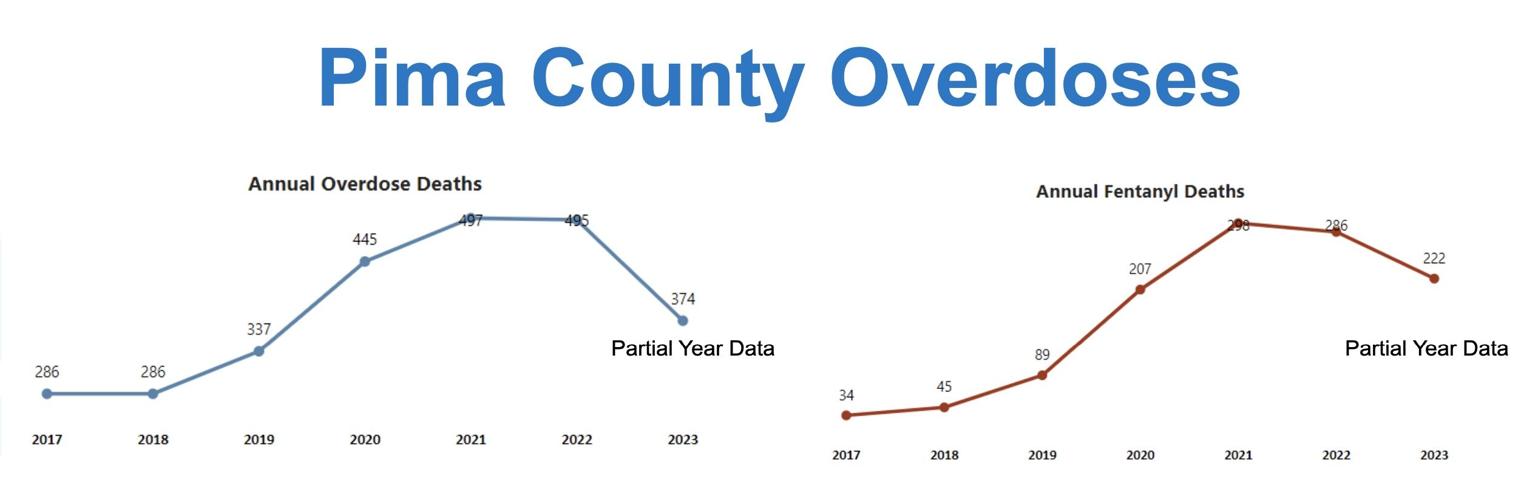

The highly addictive, relatively cheap synthetic opioid was responsible for 286 fatal overdoses in Pima County last year and 222 so far in 2023. Since 2017, the year former Gov. Doug Ducey declared opioids a public health emergency, fentanyl-related deaths have increased by more than 500% throughout the county.

Brendon Bond, peer support specialist with CODAC.

Tucson City Council declared the widespread use of fentanyl a public health crisis on Oct. 17 and directed City Manager Michael Ortega to come up with a plan to work with Pima County, the designated health authority for the region, “to create a roadmap to address this crisis.”

Pima County is set to see increased funding to combat the opioid epidemic beginning this year, with a $12.5 million grant from the CDC distributed over a five-year period. The One Arizona Opioid Settlement Funds — the result of settlement agreements from major opioid distributors that all 15 Arizona counties signed onto in 2021 — will also provide yearly funding amounting to $48.5 million over the next 18 years for Pima County and its encompassing jurisdictions.

In fiscal year 2022, the county pooled five different grants for a total of about $1.3 million dedicated to the opioid crisis. This fiscal year, the available opioid-related funding is nearly $3.3 million in the health department alone, and not including the aforementioned grants.

But even Dr. Theresa Cullen, head of the Pima County Health Department that’s leading the charge on the region’s opioid response, acknowledges, “We’re not going to buy ourselves out of this.”

“This a very complex problem. There’s not a vaccine, there’s not one thing, it needs complex solutions,” she said. “I think without funding, we would be in dire straits. With funding, we have the opportunity to do some things.”

222 people have died from fentanyl overdoses in Pima County this year.

Jail vs. treatment

While the new funding will help administer programs to prevent opioid addictions and treat those suffering from them, strategic programs to combat fentanyl are not new to Tucson. The Tucson Police Department introduced a deflection program Bond works with in 2018 where officers have the choice to offer treatment to those suffering from substance use disorders instead of arresting them.

Patrol officers attempted deflection with 2,129 individuals from 2018 through 2021, a study of the program from the University of Arizona’s Southwest Institute for Research on Women found. Of those, 45% were taken directly to a treatment provider, 29% declined treatment, 21% said they would seek treatment on their own, 2% were arrested for previous warrants and the remaining individuals’ outcomes weren’t reported.

The study said taking people to treatment centers saved time compared to arrests — deflection incidents took an average of 48 minutes to complete, while arrests took about 74 minutes. The total cost savings of the deflections, compared to arrests, was $28,529, according to the report.

But the number of drug-related arrests has far surpassed deflections in 2023, according to TPD data. Drug possession arrests have increased to 3,844 so far this year, an 83% increase from last year. Deflections have decreased by 27%, TPD data show.

TPD Chief of Police Chad Kasmar acknowledges, “The data shows that (deflection) works. When somebody’s ready for treatment, that is absolutely the best course of action for our staff to take,” he said. “But there’s a huge asterisk there. Somebody’s got to be ready for that treatment.”

Tucson Police Chief Chad Kasmar

The topic of fentanyl and its entanglement in Tucson’s homeless population has been a key talking point among a community of local business leaders and has seeped into the politics of the upcoming general election. On the night of Jan. 24, when The Tucson Pima Collaboration to End Homelessness conducted its point-in-time count that provides a snapshot of those experiencing homelessness on a single night, 80% of adults with a substance use disorder experiencing homelessness were unsheltered, according to the count’s findings.

Mayor Regina Romero has championed a housing-first policy that doesn’t require barriers such as drug treatment for shelter and said at the council’s Oct. 17 that “A lot of people confuse putting the effects of what fentanyl and opioids is causing in our families and our individuals on the shoulders of our public safety team.”

“It is not one single cause of addiction or substance use that we can point to or a single problem that stems from it,” she said. “In reality, it’s a super complex issue and we have an opportunity as a city of Tucson, and Pima County and the Public Health Department in Pima County to tackle, head on, in partnership.”

Republican mayoral candidate Janet Wittenbraker said her number one priority is “fighting fentanyl” at a forum hosted by the League of Women Voters of Greater Tucson, and said, “You crack down on fentanyl through law enforcement.”

Independent Candidate Ed Ackerley said, “The people that are creating a fentanyl habit here, those are the ones that we need to enforce, and we give them choice A or B: they either go get some help or we incarcerate them.”

The Tucson Crime Free Coalition has documented open-air drug use among seemingly homeless individuals and called for action from the region’s elected officials.

Josh Jacobsen, a restaurant owner and steering leader of the coalition, said it’s important to offer treatment for those who will accept it, but also took the hard-and-fast stance that “for the folks that just continually break the law, we’ve got another place for them as well, and that is the Pima County Jail.”

But according to Daniel Barden, the chief clinical officer at CODAC, those with substance use disorders currently face this dichotomy anyway.

“People have assumptions about the deflection program, and that we’re just taking all these people to treatment instead of the jail … when the reality is, most people are declining treatment, and would prefer to go to jail,” he said. “I’ve been doing substance use treatment for a long time, and it’s not unusual for people to think that going to jail is easier than going to treatment.”

Nick Lopez, a medical assistant at the CODAC at 380, Medication Assisted Treatment center, logs in the results of drug tests on Oct. 26.

The unwillingness among many of those with substance misuse disorders to seek help comes from the nature of the drug many Tucsonans are using, according to substance use disorder experts like Barden. Fentanyl is not only used on its own, it’s often mixed in with other illicit drugs like methamphetamine and heroin, creating variable addictions with several compounding factors.

“We see huge differences in people who are using fentanyl, as what we saw when people were using Oxycodone, heroin, or the other drugs,” said Barden. “(Fentanyl) seems to be that much more seductive to people in which they’re that much less willing to give the drug up when they’re offered the opportunity to give the drug up. It’s also dirt cheap.”

As fewer people accept treatment through TPD’s deflection program, Kasmar said, “You can certainly leverage someone through arrest.”

But as drug-related arrests have increased under his leadership, Kasmar said, “I think what that shows you is this is not just a police problem that we can arrest our way out of.”

As Tucson City Council brings attention to the fentanyl crisis through a public declaration, and Pima County begins spending funds directed at addiction prevention and treatment, the sentiment of the heavy lift of the task resounds throughout both governments.

“There is no major city in this country that is not dealing with crime challenges, including the unsheltered population — which has exploded — and fentanyl is a driver of that. We’ve never had a drug like that in this country that has been so potent and has flooded all communities in this country,” Kasmar said. “If it wasn’t for the demand, we wouldn’t have the supply.”

Cullen from the health department says the county’s doing everything it can to address the fentanyl crisis.

“I actually am not sure anybody really knows what to do beyond what we’re doing,” Cullen said. “I don’t think right now, there’s some secret sauce that somebody’s doing that I don’t know about.”

Funding incoming

The Pima County Health Department released an opioid response plan in 2021 that involved key strategies like educating stakeholders, mitigating moralities, engaging with those affected by opioids and collecting data.

The county has made widely available its supply of Narcan, a drug used to temporarily reverse an opioid overdose, at libraries and other community distribution sites. The health department’s communications team started a campaign called “End Stigma“ to spread the message about the prevalence and dangers of substance use.

But Cullen hopes the county’s receipt of the CDC’s Overdose Data to Action grant that will provide about $2.5 million yearly for overdose prevention over the next five years will help spur improvement.

One of the biggest gaps in Pima County’s opioid response plan is data sharing between the dozens of government and community agencies that interact with those suffering from substance use disorders. The county doesn’t know whom first responders interact in the field, nor the outcome of a patient transferred for care at CODAC. Sharing that information could serve as an invaluable resource when studying best practices.

Pima County Health Director Dr. Theresa Cullen

“When police interface, law enforcement interfaces, first responders interface, judicial systems interface, if there’s not a handoff to public health … we can’t do anything. We don’t know who you are,” Cullen said. “We have to have the ability to interface, have contact, do a linkage to care.”

Kasmar said TPD would be more than willing to participate in a “data lake” of centralized, aggregated data. While both the county and city want to share data, he said, there are technical and security issues with doing so.

“It gets complicated within protecting our systems, that tends to be the impediment to rapid data sharing. It’s not the desire to share, I think everybody’s at that point within metro government,” he said.

The new CDC funding will also go toward a new public health strategist position to conduct cross-jurisdictional work while staffing other positions like peer navigators and tribal case managers, Cullen said.

The regional money from the One Arizona Settlement Fund is more complicated to disperse, as each jurisdiction within the county can either decide to pool their money into county-wide efforts or take their allotment for themselves. So far, Marana and South Tucson have committed to pool their portion of the funds, while Oro Valley and Sahuarita have taken them. The county is awaiting a decision from Tucson.

The exact uses for the region-wide $48.5 million over the next 18 years have yet to be established. The county put together a Substance Misuse Advisory Committee, assembled a group of 20 external advisors and put out a community survey to weigh in on how to spend the money. The county’s Board of Supervisors will have the final say.

So far, the priorities identified include mobile intervention, peer-recovery centers and training emergency room personnel, among a variety of other suggestions.

Over the next several years of increased funding to address opioid addictions, Cullen thinks the region can make a positive impact.

“I am optimistic. I do believe that collectively, we can address this. Will we make addiction go away or substance abuse go away? No. But can we minimize the impact on the individual, the family, the community and the economics? I think yes,” she said.