Friday’s rain and more predicted for Sunday are a boon to people, plants and mosquitoes in Southern Arizona.

This wet early April is a good time for a semi-dry run in mosquito-abatement techniques that we will need to deploy in earnest when the real rain arrives with the monsoon in July.

Mosquito-borne diseases don’t usually appear until late summer in Arizona, but the Arizona Department of Health Services considers April to be the start of the “active mosquito season.”

Public health officials will be ramping up their annual messages about avoiding mosquito bites and the diseases they may carry this summer as the United States braces for expected transmissions of Zika virus, carried by Aedes aegypti mosquitoes, which have already colonized most of southern and central Arizona.

Zika, which is rampant in South America, has not been transmitted in the continental United States, but it has been confirmed by the Centers for Disease Control in 346 travelers returning from affected areas, including one female traveler in the Phoenix area.

Human travelers are the only pathway the disease can take. The mosquitoes themselves don’t travel far — a block or two at most. Swarms of Zika-infected mosquitoes won’t be flying north as the weather heats. A local mosquito would have to bite an infected traveler and then pass on the virus in another bite.

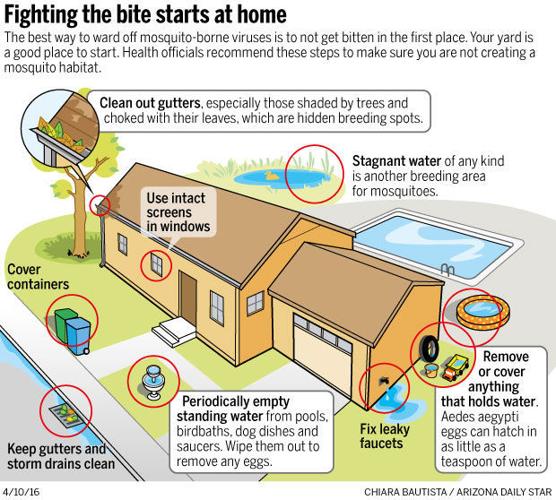

So the messages from public health experts are simple: Don’t get bitten and don’t provide mosquitoes with a place to breed.

Tough opponent

The odds of local Zika transmission in Arizona, already considered low by scientists who study vector-borne diseases, would be further lowered if we all paid close attention to our own habitats.

David Ludwig, program manager for consumer health and safety in the Pima County Health Department, suggests a weekly walk around your yard to locate and empty any standing water.

The theory is similar to the herd-immunity afforded by vaccinations. If you guard against getting a mosquito-borne disease, you also protect your neighbors.

It’s not easy. The Aedes aegypti mosquito — which can transmit dengue, Chikungunya and yellow fever viruses as well as Zika — has adapted well to urban life.

The tiny ankle-biter can breed in half an inch of water, something as easily overlooked as a fold in the tarp covering your backyard grill. It lays its eggs on damp surfaces and waits for Mother Nature or a backyard gardener to refill the container. It doesn’t need rain because it has us to supply a welcoming habitat.

The mosquito lengthens its lifespan by seeking shade in our homes, on our porches and in our gardens during brutal desert days.

It bites all day long, though it is most active after sunrise and before sunset.

And, irritatingly enough, it survives through the dry pre-summer months in the habitats we create.

increased awareness

University of Arizona public health expert Heidi Brown said most commercially installed harvesting systems take precautions against breeding, but she’s been to homes where rain gutters empty into open barrels.

Dunks containing the naturally occurring pesticide bacillus thuringiensis are recommended for any standing water source that is not regularly emptied.

They are the same treatments used by health authorities for neglected pools or standing water in washes and other drainages.

Arizona experiences outbreaks of West Nile virus every summer, though most people have no symptoms. An estimated 20 percent experience flu-like symptoms and in rare cases, can develop encephalitis and/or meningitis.

In the past five years, 34 people have died from complications caused by West Nile in Arizona.

Like other states, Arizona’s vector-control efforts have focused on the larger Culex mosquitoes that carry West Nile and St. Louis encephalitis. Aedes aegypti were considered little more than a nuisance because the diseases they carried — dengue, yellow fever and Chikungunya — didn’t transmit here. Zika was little known before a major outbreak in Brazil, where it was linked to birth defects and neurological diseases.

State and county health agencies in Arizona had begun paying closer attention to Aedes aegypti in 2014, after cases of dengue fever were reported in Mexican border communities. They are ramping up that attention this year, with Zika nearby.

The fact that dengue outbreaks occurred south of the border but not in Arizona makes mosquito researchers suspect some combination of lifestyle and climate protects Arizona from its spread. They hope the same is true for Zika.

Federal officials warn against complacency.

Last week, the Centers for Disease Control held a Zika Summit for state health officials and urged them to come up with a plan for an eventual outbreak. The biggest threat in the continental United States is still in Texas and the Gulf States, the CDC says, but all states with populations of the mosquito were urged to develop emergency plans.

Holly Ward, spokeswoman for the Arizona Department of Health Services, said representatives from her agency attended the summit and already have a Zika response plan ready.