Ronnie Sidner’s 35-year love affair with bats has come to a tragic end.

Back in the late 1970s, Sidner, then a middle school teacher in Parker, took a field course in mammals at Northern Arizona University, went on a field trip to net bats, and it was love at first sight. That led her to a career of monitoring, writing about and advocating on behalf of bats, and becoming one of Arizona’s top bat researchers.

Starting in 1980, she conducted bat research and conservation projects on national forest, national park, state park and military reserves for government agencies and nonprofit groups. She lectured tirelessly, often with a pet bat in hand, and belonged to research and working groups on bats.

But Friday night, Sidner, 63, was killed in a car crash on Interstate 10 while driving back to her Tucson home from Sierra Vista. She was returning from the Southwest Wings Festival, where she had taken participants to Ramsey Canyon south of the city to use night vision equipment to watch bats drink nectar from hummingbird feeders.

Family members said they were told by police that Sidner’s car had swerved off westbound I-10 into a median east of Alvernon Way, then went into eastbound lanes where it collided with another vehicle.

“She was one of the top bat researchers in Southern Arizona. She had the longest and broadest knowledge of any active bat researcher in this area,” said Debbie Buecher, a close friend and fellow ecological consultant who collaborated with Sidner on bat research projects for decades.

Sidner’s death leaves a huge hole in the region’s bat research community, said Scott Richardson, a U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service supervisory biologist in Tucson.

“She was a dedicated, passionate biologist who dedicated her life to the conservation of bats,” said Richardson.

She was the person to call if you wanted to know something about bats, echoed Angie McIntyre, Arizona Game and Fish Department’s bat management coordinator. “She was very knowledgeable across a wide range of species. You don’t get that many researchers with that kind of depth anymore.”

With 28 bat species known to live in Arizona, bats are a big deal here, drawing intensive research of their behavior and populations. The state’s low desert, high mountains and proximity to the tropics “provides a niche for every kind of bat, whether a grassland bat, a forest tree bat, or a desert bat,” observed Buecher. “I would bet that she handled every single species.”

Sidner made one of her biggest marks as a researcher by monitoring, with Buecher, the recovery of the endangered lesser long-nosed bat at Fort Huachuca over 25 years from zero to 19,000 animals. The research began in 1989 after fort wildlife biologist Sheridan Stone took an old gate to fence off a cave, letting bats roost there undisturbed.

The two tracked a population of about 1,000 cave myotis bats at Kartchner Caverns shortly after the caverns’ existence was revealed in the late 1980s. Using another bat-friendly gate, they monitored lesser long-nosed bats for three years at Coronado National Memorial in Cochise County at the Mexican border.

Working as a U.S. Border Patrol consultant, she monitored mine sites around high-tech towers in Southern Arizona to check their impact on the endangered bats, Richardson said. In the coming year, she was to work on similar research on a new tower, this time gathering “baseline” data on how bats use the area now.

She monitored bats’ use of bridges to help state transportation officials and railroad companies understand that use before they upgrade or replace them. She worked for Westland Resources, Rosemont Copper’s environmental consultant, using infrared lights to monitor the distribution of agaves, where the long-nosed bats feed, across the proposed Rosemont Mine site.

“The Rosemont site has a good population of agaves,” Buecher said. “This year there were so many flowering agaves that I went along one road and counted 113 flowering stalks going through there.”

Sidner was for 16 years on the faculty at the Tucson Audubon Society’s Institute for Desert Ecology, and gave talks at numerous bat and other wildlife festivals.

She helped the public understand the often misunderstood bats’ value to the ecosytem and society, Richardson said. “There are a lot of old wives’ tales that bats are blind, that bats will fly into your hair and get tangled, that all bats are rabid, that are based on misinformation and old traditions. They’re not true at all,” Richardson said.

Sidner had a gentle spirit that could turn peoples’ minds around about bats with a single talk, added Buecher.

“When you take a live bat and show someone how gentle and beautiful they are and explain what they can do, that’s all it takes to convince people that they are fabulous,” Buecher said.

Sidner was raised in Pennsylvania and obtained a bachelor’s degree in arts and elementary education at Kansas State University. Then she moved to Parker, at the California border, where she taught science for seven years.

In the late 1970s, she went to the University of Arizona, where she obtained a master’s degree in mammology in 1982 and a Ph.D. in 1997.

Explaining Sidner’s attraction to bats, Buecher said, “You just look at their faces. They’re fascinating animals. They are so intelligent. They can turn on a dime in flight, and they can echolocate.”

One of her contributions was the use of low-disturbance bat monitoring, Richardson and Buecher said.

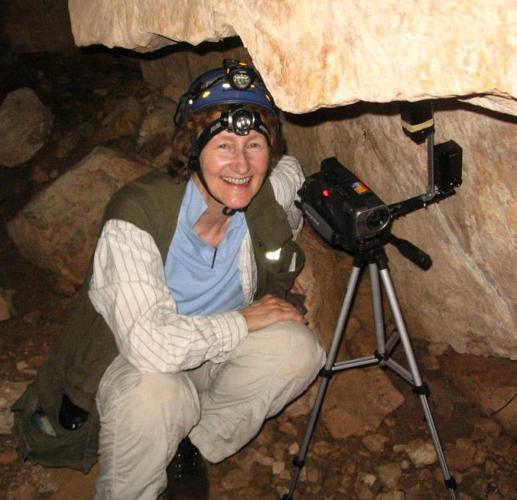

“When she was counting bats that were coming out of the roost, she would set up and use camera equipment in a way that wouldn’t affect the bats,” Richardson said. “Most of these roosts are old mines, in a small, confined space. The bats are very sensitive to any sorts of disturbance and if they get disturbed enough, they abandon them.”

Survivors include her husband, Russell Davis, a retired UA mammalogist and professor of ecology and evolutionary biology; a brother and three sisters.

Her family will have a private funeral service today. A public memorial service will be held in the future.