The U.S. government wants to stop protecting a southwestern bat species because it appears to be recovering from its endangered status.

And in a rare moment in the fractious debates over endangered species, advocates on both sides agree that’s a good idea, although for different reasons.

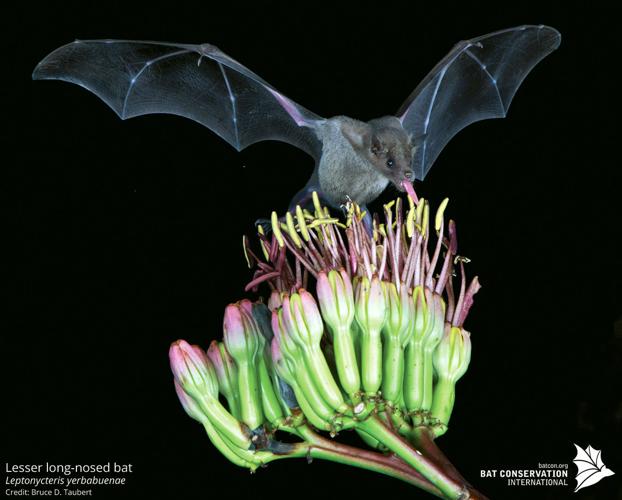

The lesser long-nosed bat, which frequents Sonoran Desert agaves, saguaros and hummingbird feeders, is proposed for removal from the endangered species list because the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service says its known population has skyrocketed in the past 30 years.

When it was listed in 1988, less than 1,000 were known to exist in Arizona, New Mexico and Mexico. Today, the known population is around 200,000.

About 90 percent of those in the U.S. live in Southern Arizona. Their roosts have been documented from Organ Pipe National Monument and the Cabeza Prieta National Wildlife Refuge on the west to the Chiricahua Mountains on the east, and in the Catalina, Rincon and Santa Rita mountains in between.

The number of known lesser long-nosed bat-roost sites in the two countries rose from 14 in 1988 to around 75 today. Bats typically roost during the day in underground areas such as caves, mines and crevices, and often roost in trees, bridges or porches at night, said Scott Richardson, a Fish and Wildlife Service supervisory biologist. The 3-inch-long bats have wingspans at least a foot wide.

Better monitoring and management have contributed to the higher population counts, the service says. Authorities are closing, fencing and putting gates in some bat caves and abandoned mines to prevent the bats from being harassed by the public, but still allowing them to fly in.

Many bat-roost sites are monitored several times a year now. Authorities use infrared video recordings instead of manual counters to track the number of birds at a roost, Richardson said.

“With infrared video, you can play back on your computer at slower speeds. They sometimes come out at 200 a minute, and you can slow the video to a quarter or half speed,” he said.

In Mexico, scientists are working with tequila producers, who cultivate agaves to make their product, to modify growing conditions to produce “bat friendly tequila,” the wildlife service says.

Biologist Rodrigo Medellin, a top Mexican scientist and longtime bat expert, has been working with tequila producers there for 10 to 15 years to show how to design harvest practices that leave areas of agave blooms available for bats, Richardson said.

About half the total bat population is migratory, flying up to 1,500 miles from central and southern Mexico to the U.S. from mid-April to October in search of food, Richardson said. Because many agave flowers aren’t available in the summer in Mexico, the bats take advantage of blooming desert plants here during that time, he said.

Environmentalists, ranchers and some scientists were at loggerheads over lesser long-nosed bat protection for many years. But today, the Center for Biological Diversity and Arivaca rancher Jim Chilton support the bat’s delisting.

For the center, the bat’s recovery shows the oft-denigrated Endangered Species Act is working. The Obama administration delisted 23 species and proposed another eight including the bat for delisting, making a total species recovery count larger than in all other presidential administrations combined, the wildlife service says.

“The act has saved more than 99 percent of the creatures and plants placed under its care from extinction. And it’s put hundreds more ... on the road to recovery,” said Michael Robinson, a conservation advocate for the Center for Biological Diversity.

Rancher Chilton, who petitioned in 2007 to reduce the bat’s protection, said the new proposal shows him the bat never should have been listed to begin with.

About 55 percent of his 25,000-acre grazing allotment near the Mexican border was closed to cattle because Forest Service and Fish and Wildlife Service officials said grazing could impact the bat, although none were found on his property, Chilton told a U.S. Senate subcommittee in 2003. The cuts knocked $150,000 from his annual income, he testified.

Since then, biologists have concluded cattle grazing doesn’t affect bats as much as once thought, and grazing cuts made in the bat’s name have been removed, Richardson said. The Forest Service says no grazing restrictions now exist on the allotment to protect the bat.