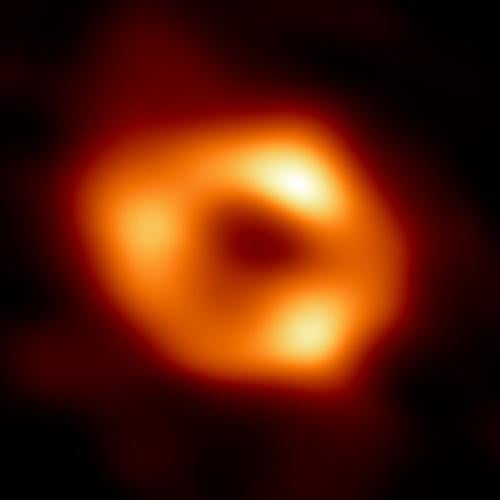

The team that produced the first picture of a black hole has revealed a new, never-before-captured image of the supermassive singularity churning away at the center of our own galaxy.

And a researcher from the University of Arizona was at the center the groundbreaking announcement.

The black hole known as Sagittarius A*, or Sgr A* (pronounced “sadge-ay-star”), resembles a fiery, fuzzy donut in the images painstakingly assembled by the international Event Horizon Telescope Collaboration.

The orange ring is formed by superheated gas spinning down into an infinite black gravity well 4 million times the mass of the sun, so dense not even light can escape.

The first direct visual evidence of the black hole at the heart of the Milky Way was unveiled Thursday morning by UA professor and founding Event Horizon member Feryal Özel and a panel of experts at a news conference hosted by the National Science Foundation in Washington, D.C.

“It took several years to refine our images and confirm what we had, but we prevailed,” Özel said.

University of Arizona scientists, from left, Feryal Özel, Chi-Kwan Chan and Dimitrios Psaltis, are among 36 University of Arizona researchers,…

She has been studying this black hole near the constellation Sagittarius since she was a graduate student more than 20 years ago. She said seeing a picture of it is like meeting a friend in person for the first time after decades of chatting online and getting acquainted from a distance.

“‘Oh, you’re real.’ It’s a very nice feeling,” Özel said. “We love our black hole.”

‘Gentle giant’

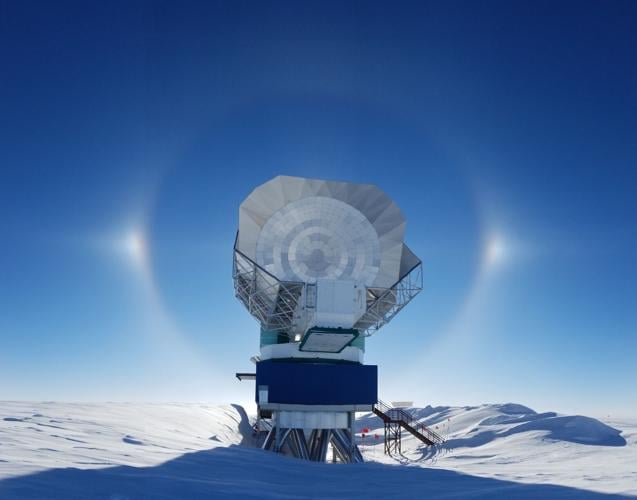

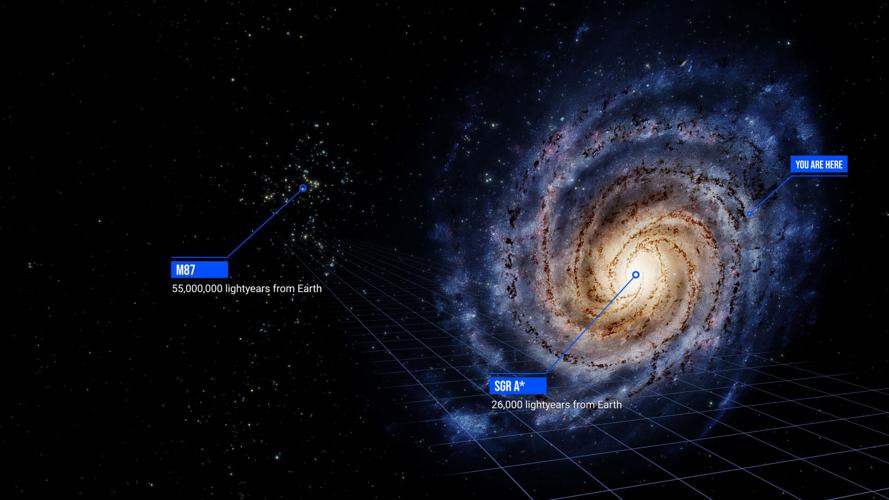

The unprecedented picture is based on observations made in 2017 by eight radio observatories around the world, including two affiliated with the University of Arizona: the Submillimeter Telescope on Mount Graham and the South Pole Telescope in Antarctica.

The observatories were linked to form what amounts to a single Earth-sized telescope. Dozens of scientists around the globe — including 36 researchers and students from the UA alone — were involved with collecting the observations and processing them.

The University of Arizona's Submillimeter Telescope on Mount Graham is one of eight observatories around the world used to capture the first i…

The site in Antarctica proved especially valuable, because its view of the black hole, 25,640 light years away, is never blocked by the tilt or rotation of the Earth.

“Imaging Sgr A* took an entire planet,” said Vincent Fish, a research scientist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology who joined the EHT team 15 years ago.

Back then, the black hole was difficult to even detect, he said. Capturing an image of it “seemed like a hopeless task at the time.”

The eight Event Horizon telescopes collected some 3.5 petabytes of data, roughly the equivalent of 100 million TikTok videos, Fish said. “It’s too much data to move over the internet. We actually have to ship hard drives around.”

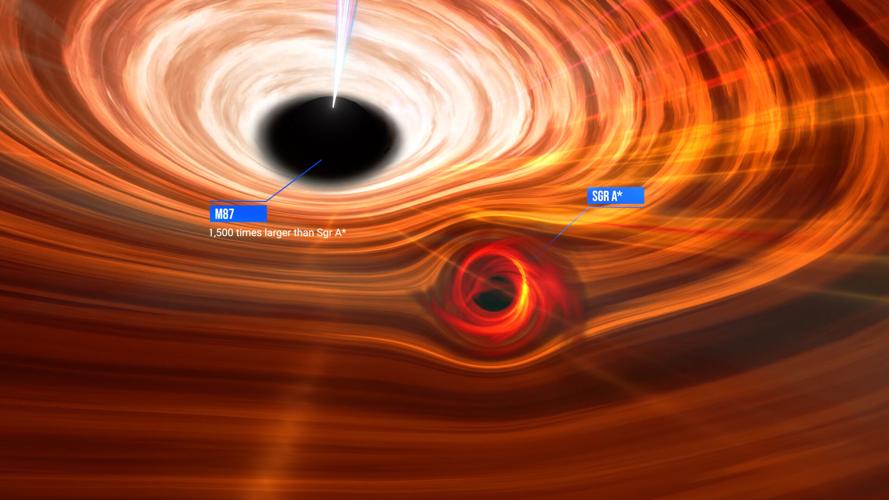

In the resulting image, Sgr A* looks a lot like M87*, the first black hole ever photographed by the EHT team or anyone else. But the two objects are actually very different.

M87* is one of the largest black holes in the known universe — roughly the size of our entire solar system — and it is pulling in matter at a much higher volume than Sgr A*. It also emits an immense jet of energy that reaches to the edge of its host galaxy, known as Messier 87 in the constellation Virgo.

With no such jet, Sgr A* is a “gentle giant” by comparison, Özel said, though its glowing orange halo is made up of atoms that are being torn apart at temperatures in the trillions of degrees Celcius as they plunge into the void.

The similar appearance of the two black holes is partly due to distance. Though M87* is about 1,500 times more massive than Sgr A*, it’s also about 2,000 times farther away from Earth.

Good one, Einstein

In some ways, the more distant black hole made for a steadier target.

Even at nearly the speed of light, gas can take days or weeks to orbit M87*, so images of the black hole all look generally the same.

But the swirl of material around the much smaller Sgr A* changes by the minute, leaving scientists to make sense of an object that “burbled and gurgled as we looked at it,” Özel said.

“It changes quickly, so we have to collect our data quickly,” Fish added.

An illustration shows the vast difference in size between the first two black holes ever imaged by telescopes: Sgr A* at the center of our Mil…

The team also had to compensate for distortion from the Earth’s atmosphere and “noise” from trying to see into the center of the Milky Way through its spiral arms.

EHT team member Michael Johnson, from the Smithsonian Institution and Harvard University’s joint Center for Astrophysics, compared it to peering at something through frosted glass.

He said the image released Thursday looks fuzzy and out of focus because “we’re pushing our instruments to their limits” just to be able to see anything at all.

Based on the sheer amount of data used to produce it, though, it’s actually “one of the sharpest images ever taken,” said Caltech professor and EHT team member Katie Bouman.

What astronomers can see in the picture so far closely matches theoretical predictions made using Einstein’s Theory of General Relativity, which Özel said has just passed its “most practical test to date.”

Named for the boundary in a black hole beyond which no light can escape, the Event Horizon Telescope Collaboration was founded in 2009 by an international team of astronomers interested in studying the universe’s mysterious, star-eating monsters. A decade later, the group released the first picture of a black hole ever made.

Today, EHT’s global array features 11 observatories, including the UA’s 12-meter Telescope on Kitt Peak.

Team members are now refining their techniques in hopes of producing even sharper images of both Sgr A* and M87*.

And more wonders could be on the way.

Fish said they hope to add more telescopes to their network over the next few years, with the goal of one day capturing a high-resolution movie of a black hole chowing down on the cosmos.