For decades, the U.S. Forest Service has said it can’t say “no” to a mine on its land.

Now, the recent federal court ruling overturning approval of the Rosemont Mine on service land near Tucson will make it harder for the Forest Service to say “yes.”

Legal experts say U.S. District Judge James Soto’s July 31 ruling, if upheld in higher courts, will have national repercussions.

They’re using words like “chaos,” “shocking” and “blockbuster” to discuss the ruling’s ramifications.

The ruling could chill the hard-rock mining industry that has lived under a generally favorable legal climate since Congress passed the 1872 Mining Law to encourage mineral exploration of public lands.

Mining industry lawyers say the ruling usurps the role of government agencies in making such decisions, could bring chaos to federal mining reviews and will add more delays in permitting to an industry already having some of the longest permit times for new mines in the Western world.

Environmental law professors say the ruling is well-grounded factually and could end a century-old practice by mining companies of skirting or dodging federal law by dumping mining wastes on federal lands without proper reviews.

They say it also exposes what they see as the fallacy of having our public-lands mining governed by a law written at a time when picks and shovels were used to pull minerals from the ground.

Soto’s order is “likely the most significant federal court decision on federal mining law in several decades,” mining industry lawyers James Allen and Michael Ford of the Phoenix-based law firm Snell and Wilmer wrote in an online article.

It “will likely be received with shock throughout the hard rock mining industry,” they wrote.

John Leshy, a former Interior Department solicitor and a retired law professor, called the ruling a “blockbuster” that could finally lead to reform of the 1872 law — an effort that has repeatedly failed in Congress over the past four decades.

In the meantime, the ruling, if upheld, would make opening a big new mine in the United States on public lands very hard, said Leshy, professor emeritus at the University of California-Hastings College of Law.

The judge’s findings

Soto overturned the Forest Service’s approval of the mine, which would create 500 full-time jobs at high wages and 2,500 construction jobs, but would disturb 3,653 acres of national forest.

Rosemont also would disturb and desecrate 33 ancient Native American burial grounds containing or likely containing human remains of ancestors of the Tohono O’Odham, Pascua Yaqui and Hopi tribes, the judge wrote, as he ruled on two lawsuits, filed by four environmental groups and the other by the three tribes.

The opponents’ lawsuits successfully argued that only public lands directly above valuable mineral deposits are covered by the federal 1872 Mining Law’s definition of mining rights.

The judge found that the Forest Service had erred in approving Rosemont without determining the validity of the mining claims on 2,447 acres of public land where Hudbay Minerals Inc. wants to dump the mine’s waste rock and tailings.

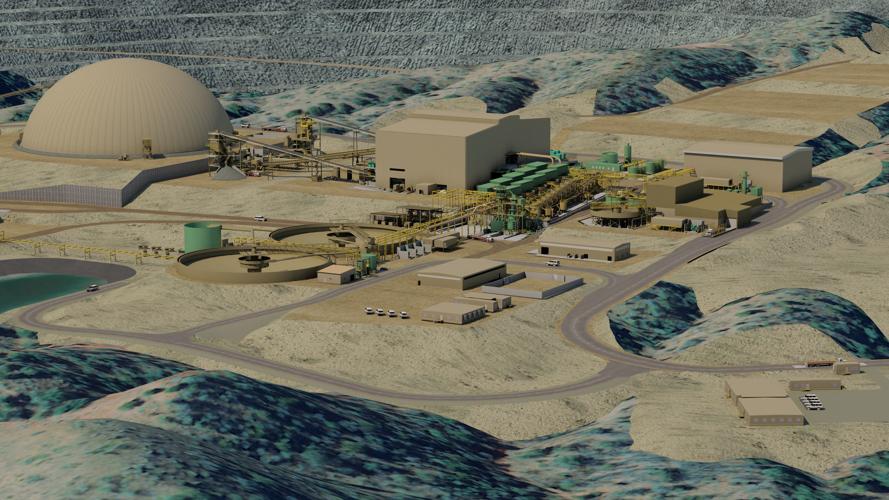

Source: The Star georeferenced an image in a Hudbay Minerals Inc. technical report of the Rosemont Mine layout plan.

To prove validity under the 1872 law, Soto wrote, Hudbay would have had to show that the land contained valuable mineral deposits, which he said the company had failed to do.

Allen, an attorney in Snell and Wilmer’s Tucson office, said: “This ruling that says you have to consider the validity of a mining claim in this context, that’s brand new. Ordinarily, validity disputes, based on discovery of a valuable mineral deposit, came up when you have two rival claimants going after the same deposit.”

Rosemont, a planned open-pit copper mine in the Santa Rita Mountains southeast of Tucson, was ready to start construction on Aug. 1.

Now, it faces delays of up to 24 months before the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals can rule on an anticipated appeal of Soto’s decision.

In the meantime, mining industry lawyer Stuart Butzier of Albuquerque said the ruling will “chill investment in domestic mining on any significant scale” and cause mining companies to look at other countries.

Said industry lawyer Daniel Jensen of Salt Lake City: “It will simply provide one more alternative for challenging the agency’s actions in court, which is never a quick process. It will slow things down.”

Soto’s ruling effectively holds that the feds cannot say “yes” to a proposal to dump mine tailings on invalid mining claims, said Mark Squillace, a University of Colorado law professor. Mining claims can only be used to extract the minerals located there, he said.

“Since dumping tailings on the claims could make it difficult or almost impossible to develop the claims going forward, Rosemont seems to be admitting that the claims do not contain valuable minerals and thus are not valid claims,” Squillace said.

The ruling will almost certainly force the industry to push Congress to overturn it, said Leshy, who worked as an informal, unpaid consultant to attorneys pressing the Rosemont suit.

“Otherwise, the Bureau of Land Management and the Forest Service will have the ability to decide whether and how to allow hard-rock mining companies to use public lands as dumps, including requiring them to pay the U.S. fair market value for that use,” he said.

“The ruling would treat those companies just like most others who seek to use public lands for profit, and the industry is not used to being treated that way,” Leshy said.

Industry attorney Allen, one of the few legal experts interviewed who didn’t take sides on Soto’s ruling, was less convinced that it would choke off all new mines. He said companies can always go back to the agencies and try to find ways to make their projects work legally.

If the ruling slows projects another two years, after Rosemont has taken 12 years to get permitted, “how much slower can it get?” he asked.

But “my sense” is that now with this ruling, industry officials may be more open to some modifications of the 1872 law if that would give them more certainty about the outcome of future permit issues, he said.

In the end, companies do not care what legal regime they are working under as long as there’s some degree of certainty, Allen said.

Waste disposal on public lands

Since the 1872 Mining Law passed, mining companies have legally dealt with their need to dispose of waste rock and tailings in two ways.

They have placed them, as Hudbay wants to do, on federal land on which they have filed “unpatented” mining claims, on which they don’t own the land but own its mineral rights.

Or, they have created what are known as mill sites to let them put wastes on those lands. That doesn’t require proof of a valuable mineral deposit but is limited to 5 acres per mining claim.

Legal experts on both sides of the issue say the use of unpatented claim land for mine wastes without a check on their validity has survived largely unchallenged until now.

Leshy, during his Interior solicitor’s tenure, wrote a legal opinion abolishing the practice, but the Bush administration overturned it during the 2000s.

In the Rosemont case, the mining claim validity issue first came up in December 2006, in a letter from Pima County Administrator Chuck Huckelberry to then-Coronado National Forest Supervisor Jeanine Derby.

This was during the early stages of company efforts to win federal approval to build the mine on 955 acres of private and federal land, with the open pit eventually reaching 3,000 feet deep and 6,000 feet in diameter.

To get access to copper, molybdenum and silver from the mineral ores, Rosemont must extract a total of 1.2 billion tons of waste rock, material containing no economic value, as Soto noted, and about 700 million tons of tailings.

Noting that Rosemont hadn’t proposed to “extract, remove or market” minerals associated with its claims on land slated for waste disposal, Huckelberry said, “This brings up the very obvious question of whether the claims are valuable if claimants do not propose to improve them but instead propose to use them as a dumping ground.”

“To save itself, taxpayers, interested parties and the claimant much time and money,” he urged the service to force Rosemont to prove that the claims are valid.

No way, Derby wrote back two months later.

She said she had received opinions from the service’s Office of General Counsel and a geologist in the service’s regional Albuquerque office that it’s not common practice or Forest Service policy to challenge claim validity.

The exceptions would occur when a mining company wants to operate on land where the service has already forbidden mining; when someone applies to “patent” a claim by getting it as their property; and when the service determines that a company’s proposed land use isn’t related to mining.

Nearly seven years later, in the final Rosemont environmental impact statement, the service said that putting waste rock and tailings on forest land is considered to be connected to mining under federal rules.

“As such, they are authorized activities regardless of whether they are on or off mining claims.” That means their validity isn’t an issue, the statement said.

In a response to the environmentalist lawsuit, Hudbay and the service said this year “the record is inconclusive” as to whether the land with unpatented claims has valuable minerals.

“However, past exploration has indicated that the area surrounding the Rosemont deposit may contain valuable mineral deposits,” they said.

Soto’s ruling bought into Huckelberry’s arguments, saying Rosemont’s proposal to bury its unpatented claim land with waste “was a powerful indication that there was not a valuable mineral deposit underneath that land.”

Geological studies and maps indicate primarily common sand, stone and gravel lie beneath the land: “This does not constitute a valuable mineral,” Soto wrote.

He noted that the Forest Service and Hudbay cited two federal laws passed a half-century apart that say mining can’t be prohibited on federal lands. One, the Multiple Use Act of 1955, also prohibits interfering with “reasonably incidental mining activities” on federal lands, which Rosemont says its waste disposal would be.

But those laws only protect mining activities permitted under the 1872 Mining Law, which isn’t the case for Rosemont’s dumping tailings and waste rock on non-valid claimed land, the judge wrote.

Environment vs. property rights

This ruling’s most significant feature is that it “breaks down the wall” between mining law and environmental law by placing a longstanding issue about the validity of mining claims into a new realm — the federal approval of a new mine under the National Environmental Policy Act, industry attorney Allen said.

Typically, mining law deals with property rights and environmental law does not. This case raises the possibility of environmental law being brought to bear on property rights, he said.

From now on, every time a company submits a mining plan to the Forest Service or BLM for approval, their plans would be at risk unless they include some kind of a mineral exam, he said.

The ruling ignores an agency’s right to not challenge or question the validity of an unpatented mining claim if it chooses, industry attorney Jensen said.

“The judge seems to believe the agency is required to do that in every case, which is not the law,” Jensen said. “The agency has discretion to do that any time it wants. It is not compelled to do it.”

Soto has pretty much usurped the agency’s role in this area, Jensen added.

“If that happened all the time, it would be chaos in the administrative world,” Jensen said. “The agency has regulations for analyzing the validity of claims, and they do challenge mining claims from time to time.

“If someone can go to court and convince a judge that a judge alone can undertake some sort of analysis on her or his own, suggesting that record is invalid and claims are invalid, that circumvents the administrative process,” Jensen said.

Industry attorney Butzier said the part of Soto’s opinion dealing with the principles of the 1872 Mining Law, public lands and multiple use “strike me as pretty sound. He’s clearly thought that through, and done research into principles that apply to public lands law, in particular related to the 1872 law.”

Butzier’s concerns lie first with his view that “it’s not clear that Rosemont had the opportunity to put forward evidence as to whether there was a valuable mineral deposit” under the lands slated for waste disposal.

Second, he is concerned that the court’s use of the National Environmental Policy Act to handle challenges to mining claims is the wrong forum.

“To me, that’s an apples-and-oranges detour from the purpose of NEPA, which is to evaluate alternatives for a proposed action affecting the human environment,” he said.

Attorney Jensen’s view is what former Interior Solicitor Leshy said he expects will be the industry and government’s arguments during an appeal.

“It’s basically saying, the government can stick its head in the sand and not look at the obvious, and the courts should not intervene to stop it. It’s kind of a ‘prosecutorial discretion’ argument — the government gets to decide when and whether to challenge the validity of mining claims,” he said.

But although the government gets a good deal of deference, it can’t act “arbitrarily and capriciously,” said Leshy, citing a phrase from Soto’s ruling.

“It is arbitrary and capricious for the government to close its eyes to the plain facts in front of it — these mining claims used for tailings piles do not have minerals that can be profitably mined and are therefore invalid, and that means the company does not have a right to use them for that purpose.”

Law professors Squillace and Jan Laitos of the University of Denver praised Soto’s ruling as sound.

“I think Rosemont is going to have a tough time justifying that they are valid claims when the intent is to bury them with waste,” said Squillace. He said he was interviewed but not formally consulted by lawyers for mine opponents.

The whole purpose of the 1872 Mining Law was to grant people rights to the minerals if they could be developed, Squillace said.

Laitos called the ruling a wake-up call to mining companies that they must be sure they can convince the feds they have made a mineral discovery.

“I don’t know what the facts are. I don’t know if the judge had the facts right. But as a matter of law, the judge is completely correct,” Laitos said.

“If you don’t have that trigger of the valuable mineral discovery, you don’t have the right to use that land.”

MORE: Opinion: Location thoughts on Rosemont Mine

Your opinion: Local thoughts on the Rosemont Mine

Letter: Rosemont is short-sighted

UpdatedOn one hand, Colorado River basin states struggle to apportion the river’s water to a region whose climate future foretells warmer temperatures and drought. Water is our future.

On the other hand, Rosemont Copper is receiving a green light to devastate fresh water resources for a mine with a 20-year production span. The carrot of jobs will be followed by the stick as they disappear. Our eco-tourism industry will be damaged, our water polluted.

The Star’s Mine Tales series featured quaint stories of historic mines. Each had a short life that lives on in relics they left behind. This mine will be different only in the scope and toxicity of its debris.

We should not be tempted to sell our future for such short-sighted pennies. Twenty years: our children are not even allowed to drink alcohol legally by this age. Do we forget how quickly they grow up, and how valuable is their future?

Katy Brown

Midtown

Disclaimer: As submitted to the Arizona Daily Star.

Letter: Permitting Rosemont Mine is wrong

UpdatedThe permitting of Rosemont Mine is a Death of Many Dreams - dreams of defending our public lands for the welfare of the public, of preserving rare birds and wildlife and the pristine natural areas they inhabit, of maintaining natural watersheds and clean ground water resources for all living beings, of living in a Democratic society where the people have control over their fate, and of a government that supports and protects our local tourist economy rather than permitting it to be destroyed.

After 20-plus years of constant destruction, noise, and pollution, the Santa Rita Valley will be left with a vast chemical “lake,” 1/2 mile deep and 1 mile wide, surrounded by 4,000 acres of enormous rubble fields that will, allegedly, drain water from this area forever. For a preview, look into the massive environmental impact that Hudbay Minerals has created in Manitoba and Peru.

Whatever laws or traditions or thought processes permit this devastation MUST BE CHANGED! This is WRONG. Paradise lost.

Peggy Hendrickson

Green Valley

Disclaimer: As submitted to the Arizona Daily Star.

Letter: Where is the outcry/protest to the Rosemont Mine?

UpdatedTake a good look at the jaguar picture in the 3/13 paper --it may be the last jaguar we ever see in AZ. The ocelots will also be gone and what other wildlife?

The Santa Ritas are the most beautiful of the mountains surrounding Tucson. Having camped there some years ago, near a running stream, I saw several deer and eight coatimundis in single file, tails held high, walk thru our camp. The drives all around there are scenic and beautiful. Once the mine goes in, the natural beauty, clear water and wildlife will disappear. Why are there no protesters demonstrating against this destruction? Living in Madison WI in the 60's, I was one of hundreds of protesters who came out for causes with great impact. Do we want destruction and ugliness in place of natural beauty? Do your part to stop this mine!

Jacque Ramsey

Oro Valley

Disclaimer: As submitted to the Arizona Daily Star.

Letter: rosemont mine

UpdatedMort Rosenblums recent article on the proposed Rosemont mine was insightful. His measure of tourism vs. mine revenues indicates that tourism creates a more sustainable stream of revenue for the state. If the mine were to be built, this beautiful and pristine place would be gone. The majority of the copper and its revenues would go to foreign countries and the resulting blight would be ours forever. Our water resources would be vulnerable. My husband and I live 12 miles from the proposed mine and wonder what it would be like with trucks rumbling up and down scenic highway 82 all day. I hope the voice of the people will be heard and the EPA will veto the permit.

Joan Pevarnik

Vail

Disclaimer: As submitted to the Arizona Daily Star.

Letter: Rosemont Mine

Updatedin response to "Mort Rosenblum: The true cost of Rosemont mine", I think we need to realize that rather than reducing tourism, the mine will actually INCREASE visitor spending as vendors, and others flock to the mine to do business with them. Tourist will come to SEE the mine, as they have to many mines around the country. the mine is not going to destroy the desert and beauty that surround Tuscon. Sorry Chicken Little, but the Sky is NOT FALLING. The same people want to decry the mine turn around and support "green" energy. They do not realize that to supply the needed copper for wind turbines and electric vehicles do not realize that the "Green New Deal" would require a DOUBLING of world copper production, just to meet the USA demands for copper. Come on people, let's be real and realize the real benefits of the mine. It is time to stop obstructing and start benefiting.

Marty Col

Downtown

Disclaimer: As submitted to the Arizona Daily Star.

Letter: What Jaguars

Updated“Rosemont would do devastating damage to Arizona’s water and wildlife. We’ll fight with everything we have to protect Tucson’s water supply, Arizona’s jaguars and the beautiful wildlands that sustain us all.” Randy Serraglio, Center for Biological Diversity

What jaguars? Arizona doesn't have any jaguars. Very rarely we see one that's a visitor from Mexico. These objections to mining and walls would have more credibility if they weren't so often filled with egregious hyperbole.

Jim McManus

East side

Disclaimer: As submitted to the Arizona Daily Star.

Letter: Proposed Rosemont Mine

UpdatedState highway 83 is the only road accessible to the proposed huge open pit mine called Rosemont. From the Rosemont road intersection with the highway 83 driving North to the Interstate 10, the road lanes are dangerously narrow for a 4 mile section to milepost 50. The highway lanes narrow to 8.5 feet in each direction and along the way steel guard rails are 1 foot from the right white line. No pull off and windy narrow roads could result in dangerous driving conditions especially in sharing with large rock haulers from the mine. I think ADOT allowed a road usage permit in error and I can envision litigation “down the road “.

Hank Wacker

Sonoita

Disclaimer: As submitted to the Arizona Daily Star.

Letter: Rosemont Mine

UpdatedIn his excellent piece of March 10, Rosemont go-ahead casts aside EPA fears over Water, Reporter Tony Davis reports that The Army Corps of Engineers has issued the final permit required for the Rosemont Mine Project over the strong objections of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). The Rosemont Project was ill- conceived from its very inception, and represents yet another desecrating assault on our shared and essential habitat. In this era of drought and looming water shortages, Rosemont makes absolutely no sense, even for the shareholders of the Hudbay Corporation, its Canadian-based developer. To justify it decision, the Army Corps states repeatedly that Rosemont will only affect 13% of the watershed. If I drink a glass of water that is 87% clean, but 13% has cyanide in it, the result will be deadly. We have to wake up the reality of our finite resources and their fragility before it is too late.

Greg Hart

Midtown

Disclaimer: As submitted to the Arizona Daily Star.

Letter: Rosemont Mine

UpdatedRe: “Rosemont go-ahead casts aside EPA fears over water”

President Trump is probably the only power who can stop the Rosemont Mine. Please contact him.

David Ray

Midtown

Disclaimer: As submitted to the Arizona Daily Star.

Letter: Rosemont Mine Sellout

UpdatedDrive a few hours east to Morenci, Arizona and look at one of the world's largest open-pit copper mine with reserves of 3.2 billion tons. I was raised in this town and know first hand about environmental devastation. This man-made destruction is visible from our space station. Someday, the Rosemont mine will closely resemble Morenci. The water, toxic waste, and wildlife issues have been studied and ignored. Supporters argue that we need more copper, but don't tell you that worldwide there is no shortage. Chile, Peru, China, Mexico, and Indonesia are the world's top copper producers and it is said nearly 6 trillion tons of estimated copper resources exist. US Geological surveys show there are approximately 200 years of unclaimed resources are available. In addition, nearly 80% of all copper mined is recycled. So we will have more jobs and more tax revenue, but this beautiful wilderness will cease to exist. When it's gone, it's gone. Once again, greed and the mighty dollar triumph over our environment.

Judy Bullington

West side

Disclaimer: As submitted to the Arizona Daily Star.

Letter: Saving the San Pedro River

UpdatedTwo environmental issues critical to southern Arizona have been awaiting decisions by the Army Corps of Engineers, Rosemont Mine and the Villages at Vigneto development near Benson. On Friday, the Army Corps issued a permit that allows the mine operation to begin.

Rep. Raul Grijalva and Rep. Ann Kirkpatrick together made a last minute plea to the Army Corps to reconsider its impending approval of Rosemont. Now their unified voice is needed to request that the Army Corps give adequate consideration to reinstating a permit to allow the 28,000 home Villages at Vigneto to proceed near the San Pedro River. This proposed mega-city will threaten the vital streamflow and riparian habitat of the San Pedro.

If our representatives speak out now, maybe at least one of two environmental nightmares can be avoided.

Debbie Collazo

West side

Disclaimer: As submitted to the Arizona Daily Star.

Letter: Rosemont Mine

UpdatedRosemont Mine has finally been given the OK to build the mine in the Santa Rita Mountains. According to reports, the copper there will take about 20 years to extract. If a person goes to work there at the age of 20 or 25, when the mine closes they will be out of work with still half of their work life ahead of them and they will need to relocate to continue their mining career. So after only 20 years, Tucson will lose 500 good paying jobs and be left with a huge scar on the mountain and the degradation of an ecosystem that may never recover. Is it worth it? I think not.

Sandra Hays

Northwest side

Disclaimer: As submitted to the Arizona Daily Star.

Letter: Looking forward to the economic boost of the Rosemont mine

UpdatedI am very pleased to read that the US Army Corps of Engineers has given final approval to the construction of the Rosemont mine.

I have long supported Rosemont for its significant contribution to the economic development of Southern Arizona and for its wise use of the copper resources that our Creator - sorry, atheists, not - bestowed upon our part of the globe.

I too have an interest in the environment but not to the extent of preventing the sound, environmentally-respectful development of this mine. I make my living teaching via computer and telecommunications, and they needed copper to be built and run. So do many other things that I use.

As for the American Indians / Native Americans who protest, they should be thankful that Rosemont will benefit them too if they take advantage of its work opportunities, plus the increased tax revenues will make it a little easier for the government to fund the highly-subsidized reservation system for those who choose not to assimilate into broader American society.

James Stewart

Foothills

Disclaimer: As submitted to the Arizona Daily Star.

Letter: The Cost and Legacy of Tainted water ??

UpdatedA month ago, you ran a Business article ( Rimini, Montana 2/21/19) on the unspeakable outrage of Mining legacies that poison and taint long after mines are abandoned. The state of Arizona and the United States permit this contamination for unfathomable reasons.

It is not a secret and is a nation-wide and world-wide travesty. Why - is this allowed ? Who agrees to allow it and even invite other nations to purchase precious land and metals for their own profit ? How long does arsenic, lead , zinc and worse continue to contaminate the water, wells, streams and land once poisoned ? To quote the above article: “ the waste is captured or treated in a costly effort that will need to carry on indefinitely , for perhaps thousands of years often with little hope . ..”

When, Who, How and What will it take for Arizona and Pima county STOP the Rosemont Mine ?

Please, the cost of too high !

Susanne Burke-Zike

Oro Valley

Disclaimer: As submitted to the Arizona Daily Star.

Letter: Where's the outcry?

UpdatedWith our water supply threatened by overpopulation and global warming and Lake Mead looking like a half-drained bathtub, comes the news that Rosemont Mine will be approved. The 75,000 trees and the beauty of the mountain will be destroyed. The precious water will be polluted despite the denials of the "experts." Look at water supplies around the country that have been/are being polluted by mines. And this is for a FOREIGN COUNTRY to sell copper to a FOREIGN COUNTRY.

Where is the outcry? Where are the mayors of Tucson, Sierra Vista, and Green Valley, senators, representatives, City Council, and Daily Star editors? We once marched against the Iraq war, and look what happened. As Shakespeare said, "What fools we mortals be!" Or Pogo: "We've met the enemy, and it is us."

Diane Stephenson

Foothills

Disclaimer: As submitted to the Arizona Daily Star.

Letter: Questioning the Corps of Engineers

UpdatedThe U.S. Army Corps of Engineers is a law unto itself. Some years ago, The Atlantic ran an article, "The Public Be Dammed," on the Corps, and it has been damming and damning before and since.

For over 90 years the Corps has been responsible for dams and navigable rivers, yet the floods and flooding continue. Why? Because the Corps is rewarded with funding to clean up the mess it was responsible for. The flooding of New Orleans, for which the Corps was entirely responsible, cost about one billion dollars. The National Review commented, "Never has incompetence been so richly rewarded." It should come as no surprise for the Corps to allow the construction of the Rosemont Mine.

Andrew Rutter

Midtown

Disclaimer: As submitted to the Arizona Daily Star.

Letter: Rosemont Mine

UpdatedThe ASARCO Mission Mine South of Tucson is located COMPLETELY within the Tohono O'Odham Indian reservation; I worked there for 12 years and as a heavy truck driver, we would go from the main pit to the San Xavier North pit, a distance of 2-3 miles . Many times I would see deer, bobcats, javelina, rabbits, wild horses, etc. on the road . At the San Xavier North pit, there was a water pipe stand water trucks would use to fill the 10,000 gallon water trucks, and the overspill would fill a small waterhole that wild horses would use to drink. Many workers would want to buy wild horses from the Tribe but would be told they were not for sale. Now all of a sudden the Tohono O'Odham and other tribes are against the Rosemont Mine!!?? All wild life in that area to the trucks, etc. No different in this case

Hector Montano

South side

Disclaimer: As submitted to the Arizona Daily Star.

Letter: Copper vs water

UpdatedIt will be a sad day in Arizona should Toronto-based Hudbay Minerals Inc. receive approval for the Rosemont Mine. The critical issue is the value of copper over water. We can live without more copper. Clean water, however, is necessary for survival. Water is more precious than any mineral the mine can extract.

Hudbay is just another foreign-based company robbing Arizona of its natural resources. Long after Hudbay has finished raping the land, polluting the water and air, our children will be left with their mess. I predict in 50 years the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and EPA will collectively wring their hands and bemoan, “What were we thinking?"

Robert Lundin

Green Valley

Disclaimer: As submitted to the Arizona Daily Star.

Letter: Ann Kirkpatrick, Raul Grijalva: Anti-Capitalists

UpdatedNew District 2 Congresswoman, Democrat Ann Kirkpatrick, and District 3 Congressman, Democrat Raul Grijalva, are anti-capitalists. The Star (3/1/19) reports they are against development of the Rosemont copper property 30 miles southeast of Tucson.

Their contrariness puzzles, for they serve citizens of Cochise, Pima, and Santa Cruz counties who will benefit hugely from Rosemont. An assessment by ASU’s W.P. Carey School of Business (2009) reports the operating mine will bring the counties 2100 jobs.

Annual revenues to counties will be $19 million; State, $32 million; Federal, $128 million. Surely, Pima County will pigeonhole its portion for road repair. Following reclamation, there are “lasting positive effects” for Arizona.

After a 12-year plod through steep EPA mining regulations and the hostility of no-growth enthusiasts, Rosemont is in the last phase of approval, finally.

Rosemont is a great example of capitalism that will wonderfully benefit so many families that these Representatives, oddly, oppose.

D Clarke

Sahuarita

Disclaimer: As submitted to the Arizona Daily Star.

Letter: Copper mining in the Santa Rita Mountains

UpdatedRe: the March 1 article "Grijalva: Rosemont Mine is on verge of final OK."

While Hudbay Minerals of Canada rapes our beloved Santa Rita Mountains, makes millions or more selling the copper and then pays our community a pittance of $135 million and provides 400 jobs until the mine is dead, we lose a pristine, unspoiled wilderness forever.

If claims were made that copper laid under the nave of Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris, would Hudbay crave it, too? Aren't the Santa Ritas as sacred? I beg you to pay attention and act against this travesty in any way you are able.

Jane Leonard

Oro Valley

Disclaimer: As submitted to the Arizona Daily Star.

Letter: An alarming headline

UpdatedNo, not about Donald Trump, our lying, cheating, corrupt conman president, but the imminent approval of the Rosemont mine. In a time of acute drought, when Arizona has no real plan to deal with it, how is it possible that this project will be approved. The amount of water needed for this operation is absurd. This short term project with everlasting environmental devastation that will benefit ridiculously few, is, like Donald Trump, a real disaster.

Stanley Steik

Midtown

Disclaimer: As submitted to the Arizona Daily Star.