Three tribes filed a second federal lawsuit Wednesday seeking to overturn a recent Clean Water Act permit authorizing construction of the Rosemont Mine southeast of Tucson.

This suit charges that the proposed open pit copper mine in the Santa Rita Mountains would permanently and illegally “scar the cultural landscape and destroy numerous cultural resources belonging to the Tohono O’odham and their ancestors.” It was filed by the Tohono O’Odham, Hopi and Pascua-Yaqui tribes. All three say the proposed mine area is part of their ancestral homelands.

The suit comes two weeks after a coalition of environmental groups filed a separate Rosemont lawsuit. Both suits accuse the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers of violating numerous federal laws, regulations and guidelines, including the Clean Water Act, when it approved its Rosemont permit on March 8. The permit was the last one needed for the $1.9 billion mine to start construction.

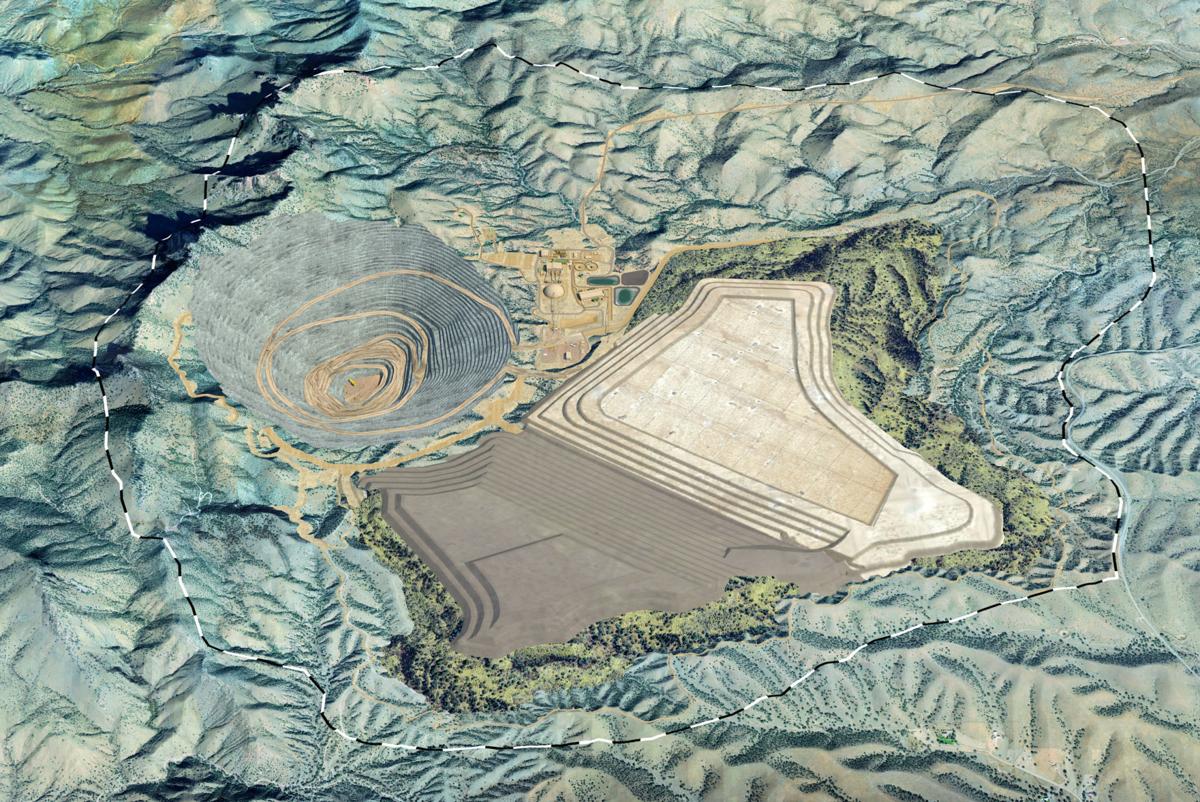

The permit allows Hudbay Minerals Inc. to place fill material on nearly 38 acres of washes on its site — material cleared and graded from surrounding land. That activity will make the mine’s construction possible.

Formal construction work is scheduled to start at the end of this year although Hudbay has announced plans to begin preliminary activity, such as building a power line and a water line sooner. But the company must first defeat efforts by opponents to get injunctions blocking construction.

There are now five pending lawsuits against the mine, including two against the U.S. Forest Service — including one filed by the three tribes in 2018 — and one against the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

The latest suit notes that past federal reviews have determined that mine construction would damage 82 historic properties, including 43 sites that contain or likely contain human remains.

The Santa Ritas, also known or Ce:wi Duag, or “Long Mountain” in the O’odham language, contain a landscape imbued with cultural significance, the lawsuit said. It has sacred sites, ancestral villages and burial sites, and is a source of plant, animal and mineral resources critical to maintaining traditional O’odham culture, the lawsuit said.

Archaeological investigations confirm Native American use and occupation of the Santa Ritas, including the proposed mine site, over about 10,000 years for ceremonial, religious and other purposes, the lawsuit said.

The Army Corps’ San Francisco regional office determined in issuing the permit that the mine would overall be in the public interest, when economic benefits such as 500 high-paying jobs and environmental impacts were jointly weighed.

It also concluded that Hudbay’s plan to rehabilitate, re-establish, enhance and preserve sections of Sonoita Creek and a 1,580-acre ranch in Santa Cruz County will adequately compensate for damages to nearly 38 acres of washes on the mine site.

And, the Corps concluded, in overturning previous findings by a Los Angeles-based Corps office and the Environmental Protection Agency, that it only should consider impacts of filling, clearing and grading washes — not impacts caused by the entire mine construction.

Limiting its scope of analysis “skewed” the Corps’ public interest finding, leading it to consider all economic benefits while examining only some costs, the lawsuit said.

Among the costs ignored were impacts to washes downstream of the mine site due to the drawdown of the aquifer required to dig out the half-mile-deep open pit, the suit said. Also ignored, it said, were the mine’s potential to degrade downstream surface water quality and reduce surface water flows at Davidson Canyon and Cienega Creek.

Impacts to fish and wildlife, loss of nature-based recreation, reduced values of neighboring properties and “the visual blight of a massive open-pit copper mine on the landscape” also weren’t adequately considered, the lawsuit said.

“The Corps has to determine there is a benefit to the public interest in destroying washes that outweighs the cost,” said Stu Gillespie, a lawyer for the tribes. “Just clearing the site and destroying archeological resources and villages — that’s a clear-cut example of a permit contrary to the public interest.”

The Corps has declined to comment on pending litigation against the agency regarding Rosemont.

Hudbay, which isn’t named as a defendant in the suit, has said in numerous letters to the Corps that opponents have overestimated impacts and used flawed analyses. The company has agreed to a detailed “treatment plan” for handling cultural resources that’s approved by state and federal officials.

But the tribal' lawsuit also says the Corps permit not only illegally authorizes the company to cover the washes with fill material, it also illegally requires the company to place the fill material in the washes before waste rock and tailings from mine operations is dumped there.

That requirement, placed in a condition for approving the permit, is to keep contamination from waste rock and tailings from entering washes, the Corps said. But it also was a "complete reversal" of the mine's entire permit review that, over eight years, had made impacts of dumping waste rock into washes a central focus of the environmental analysis, the suit said.

That action "opened the door to the subsequent dumping of waste rock and tailings without further analysis that the Clean Water Act normally requires," the suit said.

It will be illegal because the Forest Service's newly approved operating plan for the mine doesn't allow Hudbay to place the fill material cleared from the site underneath waste rock and tailings, the lawsuit said.