A growing number of neighborhoods in Pima County have COVID-19 vaccination rates high enough to cross a “theoretical” threshold into herd immunity.

The threshold is not a fixed number, but it's currently how the county’s chief medical officer, Dr. Francisco Garcia, is thinking about herd immunity, he said. It’s when around 75% of the adult population is fully vaccinated, or maybe as low as 70%.

More than 70% of adults have been fully vaccinated in 41 census tracts in Pima County, according to data, through June 1, from the county’s online vaccination dashboard.

Census tracts are roughly equivalent to neighborhoods. Rates from tracts on the Tohono O'odham Nation are not included.

These 41 census tracts are about 17% of all tracts in the county. They are mainly located in the Catalina Foothills, Green Valley, Oro Valley and scattered around areas near downtown Tucson and the University of Arizona.

They are generally areas with little social vulnerability, as measured by an index of U.S. Census data on income, age, race, language, housing type, occupation, education attainment, access to transportation and more.

The herd immunity threshold that these census tracts have crossed is theoretical, Garcia explained, because health experts still don’t have a precise estimate for the number of immune people needed to reach herd immunity, but they know it will take some combination of vaccine-induced immunity and natural immunity to get there.

Multiple factors move herd immunity’s goalpost and make it difficult to calculate the number of vaccinated people we need. For one, the real-world efficacy of COVID-19 vaccines will be different from the efficacy seen in clinical trials. And on the other side of the equation, new, more contagious coronavirus variants change the number of immune people we need to stop the virus from spreading.

The vaccination rates in census tracts where 70% of adults have been fully vaccinated are higher, by a fairly large margin, than the county’s vaccination rate as a whole.

About 54% of the adult population has been fully vaccinated in Pima County, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s online COVID Data Tracker.

The county can’t vaccinate 70% of the adult population in one fell swoop, Garcia said. “I think we do it census tract by census tract.”

It has been harder in some census tracts to raise vaccination rates, he said. He has been disappointed, for example, with the number of vaccines administered to people who live in census tract 26.03, which is an “L” shaped area near Fort Lowell Road and Stone Avenue.

“How the heck do we change that? There's only 3,255 people in that census tract. We should be able to do better than 900 vaccines,” Garcia said on Thursday, referring to the number of people who had received at least one dose. “And I need to figure that out. Our teams need to figure it out.”

This census tract is one of the most socially vulnerable tracts in the county. Its latest social vulnerability score is .98, on a scale from 0 to 1, with higher values signaling more vulnerability. The latest scores are from 2018.

Scores from the Social Vulnerability Index are meant to help officials find areas that may need additional support preparing, weathering and recovering from disasters or hazardous events.

Registered nurse Missy Pruitt gives the Moderna vaccine to a patient at the Pima County Health Department vaccination center in the former Old Navy store in Foothills Mall north of Tucson.

Most census tracts that have vaccination rates of 70% or higher among adults also have low social vulnerability scores. In other words, the most socially vulnerable people do not live in these areas.

None of the census tracts with the most social vulnerability in Pima County has achieved a vaccination rate of 70% or higher. And only 6 census tracts with high social vulnerability scores have vaccination rates, among adults, higher than the county’s average.

The Arizona Daily Star considered a “high” score one that’s in the upper quartile, or above .75. These are the places with the most social vulnerability.

The county uses vaccination data and other indicators, including social vulnerability scores, to determine where to focus additional resources, such as where to send mobile vaccine clinics.

“We focus our outreach and our vaccination efforts around those census tracts where we know that we need to make further progress,” Garcia said.

Census tracts with low vaccination rates aren't segregated to one part of Pima County, but are scattered throughout both rural and urban areas.

Sharing vaccination rates by census tract is a way to give the public an idea of “relative progress,” Garcia said. “Here's a way of showing in a very concrete way that the needle is actually moving and that this goal that we have of vaccinating a whole bunch of people is actually an achievable goal. And that we just have to chip away little by little.”

Using herd immunity as a benchmark for showing progress can be controversial among the community of public health experts.

“Some of my colleagues hate the term ‘herd immunity.’ They’re like, ‘it's inappropriate to use, it's distracting, and it's harming our message,’" said Dr. Joe Gerald, an associate professor with the University of Arizona’s College of Public Health. “While others are arguing, perhaps from a more pragmatic stance, that it’s a concept that's pretty easily understood by everybody and it can motivate collective action, so we should be doing it.”

Even with differences of opinion on how or whether to use "herd immunity" as a rallying call or a benchmark in public-health messaging, health experts agree that as many people need to get vaccinated as possible.

The topic of herd immunity comes with caveats. Garcia noted that census tracts are not islands of populations. People move between them freely, so just because a census tract has reached a vaccination rate of 70% or higher doesn’t mean that it’s risk free there.

While enough people can get vaccinated in a census tract to reach a 70% or 75% threshold for herd immunity, one tract can’t reach true herd immunity on its own because it’s too small of an area. The threshold needs to be met collectively throughout a much larger population.

“When you reach the herd immunity threshold, by definition, the effective reproduction rate has to be less than one. If it's less than one, the virus moves towards being extinguished and zero cases,” Gerald said. “If you want to get rid of your risk, you have to get vaccinated. You can't simply rely on your neighbors.”

The "effective reproduction" number is the average number of people an infected person infects as the number of susceptible people changes.

There’s also the question of how to calculate vaccination rates in census tracts. The two general options are to find the rate by looking at the number of people who have been vaccinated among the total population and the vaccine-eligible population.

“Whichever way you go, whether it’s denominator by eligible population or total population, there’s always going to be a caveat,” said Bonnie LaFleur, a biostatistician at the University of Arizona.

People ages 12 and older are eligible for COVID-19 vaccination in Arizona and across the nation. Pima County is working to use this group as the denominator when calculating vaccination rates on its online dashboard, Garcia said, but for now it still uses the number of adults, ages 18 and older, to calculate rates.

When we use the eligible population to calculate the rates, census tracts with more old people may look better because older people were eligible for vaccines first and got vaccinated at a high rate, LaFleur said.

If we use the total population to calculate vaccination rates, census tracts with more children who are not eligible to get vaccinated will look worse than tracts with more adults, Garcia said, adding that it wouldn’t be fair to include these children when gauging how close a tract is to the herd immunity threshold.

When looking at the total population, as opposed to the adult population, in each census tract, there are fewer census tracts in Pima County with vaccination rates of 70% or higher. It comes out to 19 census tracts, or about 8% of all the tracts within the county.

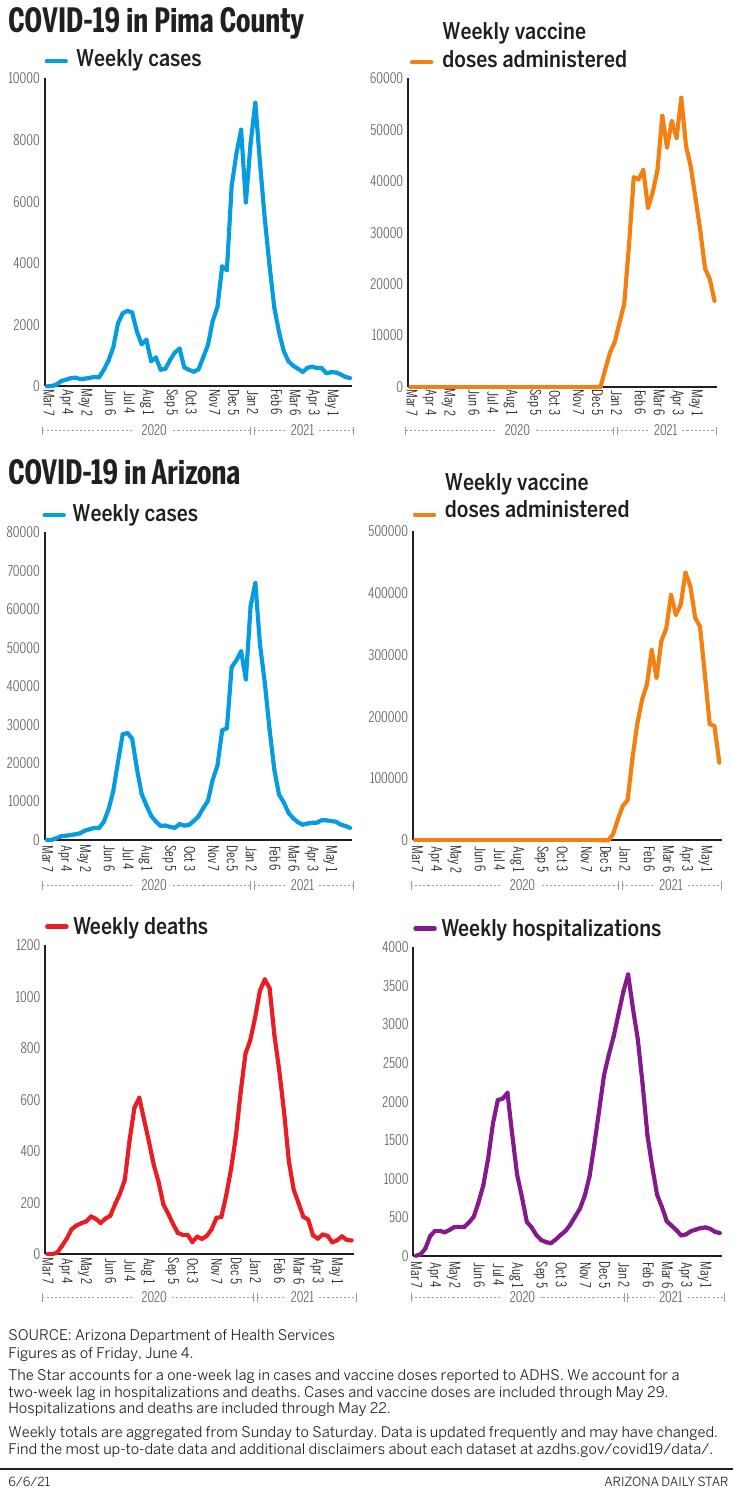

The bottom line is that the vaccination rate has come a long way in Pima County, but there’s still a way to go.

“I think we need to capitalize on making (vaccinations) as convenient as possible from as many locations,” Garcia said. “It is less important that we hit a specific number and more important that we optimize the number of people who have been vaccinated.”