Eviction orders in Pima County have already surpassed all of 2021 as officials anxiously await more emergency funds to help people avoid homelessness.

These so-called writs of restitution have been issued 2,345 times through the end of July this year compared to 2,318 times for all of 2021, county data shows. Of those 2021 orders, the county’s constables carried out evictions only 1,672 times due to a federal eviction moratorium, which discontinued about a year ago. Information was not available on how many of this year’s eviction orders have been carried out.

These numbers aren’t the only way to gauge how things are going in terms of evictions here.

Currently, more county residents facing eviction are leaving before their cases are processed — and before they might get help — possibly contributing to a growing number of people who are homeless or housing insecure.

“I would say about 40% of my eviction (orders) are for people who are already gone,” said Bennett Bernal, a constable with Precinct 6, which is bounded by Linda Vista Boulevard to the north, Interstate 10 to the west, Sixth Street to the south and Country Club Road to the east.

Bernal said he is continuing to provide information to tenants in advance of their eviction, information about shelters and information about services that are available. It’s an extension of what he started while working with former presiding constable, Kristen Randall.

Funding cliff looms for county

Both Pima County and the city of Tucson have depended on Emergency Rental Assistance, or ERA funds, to provide rent and utility assistance throughout the pandemic as part of more than $46 billion federal program that funnels the aid to state and local governments. The city received $61.5 million of those funds, and the county received about $44.2 million.

After the city ran out of ERA funds, it transferred its portion of eviction assistance cases to the county in June, leaving Pima County’s Community and Workforce Development Department to handle eviction aid for the region on its own.

The county has about $13.2 million left of the funding, which Community and Workforce Development Director Dan Sullivan estimates will sustain the program until the end of November.

As of July 12, the department had dispersed about $25 million in ERA funds to nearly 5,000 households and their respective landlords, according to the county.

The city and county have been able to expand eviction assistance after receiving more money when the Arizona Department of Economic Security failed to meet the spending threshold of the program that required recipients to use at least 65% of their ERA funds by September 2021. Some of those unused funds were rerouted to Pima County and Tucson, which have received about $17 million and $24 million in reallocations, respectively.

The county is expecting to receive another $15 million reallocation that Sullivan said would extend the program into spring of 2023, but it has yet to reach the county’s coffers.

If it takes too long for the state reallocation to come in, Sullivan worries there could be a “gap in the community.”

“When (ERA funding) goes away, we’re gonna be living like we were before, in an area of scarcity,” he said.

While the pandemic-induced eviction funds have bolstered the county’s ability to keep people in their homes, distributing funds for eviction assistance isn’t a new task for the county. It has historically provided aid through the Community Assistance Division, a sub-department of Community and Workforce Development that connects low-income residents to a variety of social support services.

Before ERA funding, however, the county had to draw from a bucket of about $10 million from various funding streams with differing and more restrictive guidelines for spending.

“The funds that we work on an annualized basis are far more restrictive and have really antiquated rules. … It was never enough,” Sullivan said. “And that’s really been the opportunity we’ve had with the ERA programs — something that I think was intended to be a pandemic response, but we saw that it was just a need.”

‘Not taking money’

The number of writs issued for an eviction is going up much more slowly than judgments entered, or eviction requests being filed in the first place.

Andy Flagg, deputy director of the county’s Community and Workforce Development, believes that’s partly due to his team of five workers helping with rental assistance, as well as people just leaving without any supports or assistance in place.

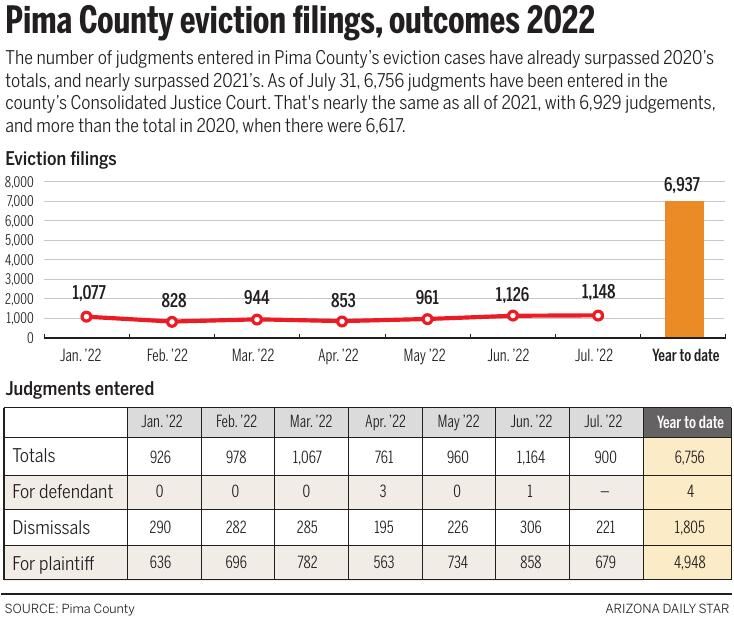

The number of judgments entered this year has already surpassed 2020’s total judgments, and has nearly surpassed 2021’s. As of July 31 this year, 6,756 judgments have been entered in eviction cases in the county’s Consolidated Justice Court. In all of 2021, there were 6,929 cases and in 2020, there were 6,617.

Of those filed so far this year, the majority were in favor of the landlord and only four were in favor of the tenant. In addition, 1,805 were dismissed for reasons that can include the county delivering rental assistance to the landlord, a tenant being able to pay up after all, or the person self-evicted.

Many of the property managers Bernal works with will wait an extra day or two beyond the time an eviction should occur in order to get rental assistance. This allows the tenant more time to find a place to go.

However, Bernal said, “a lot of the bigger complexes are not taking money because it’s taking too long.” With rental price increases booming, he said, landlords want to get tenants who can afford more.

Some of the rentals in Bernal’s 85705 area are not seeing big increases because the owners know they are not going to get tenants who can pay that much, he said.

“I think a lot of the smaller owners are realizing they are not going to be able to sustain that level so they don’t raise the price,” he said.

Impactful programs

A substantial part of the county’s eviction prevention efforts lies in the Emergency Eviction Legal Services, or EELS, program that the county launched in August 2021 to provide free legal help to those facing evictions.

Flagg, who oversees the EELS program, said he’s seen an increase in eviction filings based on nonpayment of rent, which were halted during the nearly 16-month long federal eviction moratorium that ended last summer.

However, Flagg said he’s seen an increasing willingness among landlords to hold off on eviction orders even after a judge gives the go-ahead. The EELS program can escalate cases to ensure a landlord is paid before executing an eviction.

He said the number of writs of restitution issued, which allow the enforcement of an eviction, is not going up as fast as filings or judgments. “It’s a little bit of supposition, but based on the numbers that we’re processing, I think it’s reasonable that part of the reason for that is that we are continuing to get help to people after judgment,” Flagg said.

The program has provided legal assistance to more than 1,000 households from August 2021 to July 2022, with 53% of cases resulting in tenant-favorable outcomes such as dismissal, settlement or judgment in the tenant’s favor, according to Flagg.

The EELS program is funded with a blend of ERA and American Rescue Plan Act dollars. While ARPA funds pay lawyers and provide bridge housing at hotel rooms, ERA funds are often distributed in cases where tenants owe rent and can pay landlords to settle their cases. Flagg estimates the ARPA funding will sustain the program until 2024.

“Even after ERA goes away, we’re not an exclusively ERA-funded program. So we will still be able to provide legal services until our ARPA funding runs out,” he said. “There are other ongoing programs that we’ll still be able to help get people into. It’s just that our services and the department will be more limited if that ERA funding goes away.”

While the county’s soliciting more ERA money to avoid a funding cliff that would more than halve its annual eviction assistance funds, it’s connecting people to other resources like work programs to reduce the need for government assistance.

“We’re intentionally linking people to services that look at the people, everything that’s going on with folks — it could be underemployment or lack of employment that is causing people to have to come back around for rent utility assistance — and we have programs that are specifically designed for those interventions to get people into dignified work that has the ability to sustain them and their families,” Sullivan said.

But as pandemic-era eviction assistance wanes, Sullivan hopes future funding funneled down to the county will grow to level with the need for eviction aid.

“(The loss of funding) is going to be rough. The data, I believe, will show that these programs are impactful,” he said. “And I hope that there’s a national policy or statewide policy that shows that this is something we should continue, that it’s just good for folks. You know, that this experiment worked.”