In a shiny new factory just west of Interstate 10 in Marana, workers at Roche Tissue Diagnostics are making automated instruments to help detect cancer, while across the street, two mammoth buildings are going up as part of a major new logistics center.

Across town at a sprawling site south of Tucson International Airport, startup American Battery Factory plans to make lithium-iron phosphate battery cells, with plans to eventually employ 1,000 people.

The Tucson-area economy seems to be picking up where it left off with strong growth before the pandemic, including major expansions and new arrivals in the prized manufacturing sector.

The progress aligns with local leaders’ vision of Tucson transforming itself into a technology-based economy.

But much like other areas, the region faces some significant challenges including worker shortages and a lack of ready industrial space — not to mention currently high inflation and the risk of a possible recession in the near term.

To compete going forward, local leaders say, the Tucson region must boost education and job training at all levels.

Education, training key

Finding well-qualified workers remains the top concern of companies looking to move to or grow in the Tucson region, said Joe Snell, president and CEO of Sun Corridor Inc., the area’s main economic-development group.

“Labor still drives all market decisions,” said Snell, adding that includes local expansions as well as attracting new companies.

Major new investments in technical education programs at Pima Community College promise to shore up the local pool of qualified workers, Snell said, citing PCC’s establishment of Centers of Excellence in applied technology, aviation, information technology and cybersecurity, health professions, public safety, hospitality leadership and arts and humanities.

But the Tucson area’s struggling public school districts and lagging high-school graduation rate may turn off companies and workers considering the Old Pueblo, he said.

And despite the presence of the University of Arizona and its status as a major research university, Tucson still lags in the percentage of residents with a four-year college degree or higher, Snell said.

Tucson’s college-attainment rate rose nearly 8 percentage points in 2021 to 34.4%, higher than peer markets like Phoenix and Albuquerque but still behind places like Denver, Portland and Austin.

“We’re increasing in that, but we’re still low compared to Denver, Austin, Seattle, and those cities have much stronger economies,” Snell said, adding that higher-educated voters are much more likely to vote to tax themselves to improve schools and pay for infrastructure like roads and rail.

The Advanced Manufacturing and Innovation Center at Pima Community College, downtown campus.

“Educational attainment really matters, especially that bachelor’s degree or better — that seems to be connected to innovative activity,” said George Hammond, director of the Economic and Business Research Center at the UA’s Eller College of Management. “We also need people with, associate’s degrees and certificates and we do need electricians and plumbers and carpenters, and all those all those skills are really key but they don’t seem to drive long-run growth in the same way.”

Business advocacy groups including and the Southern Arizona Leadership Council and the Tucson Metro Chamber of Commerce say improving education from preschool through college is vital to Tucson’s economy.

“If the companies can’t hire the workforce (they need), they can’t expand or move or grow,” said Ted Maxwell, president and CEO of the SALC. “A lot of times companies will bring some of their workforce with them but they’re still going to need more in this area, and especially for longevity.”

SALC, a nonprofit led by a board made up of top local business executives, has advocated for higher teacher pay, supports financial assistance for quality early-childhood education programs and is a big supporter of the Pima Joint Technical Educational District, which offers an array of technical training programs to high school students, and has supported boosting funding for community colleges and the UA.

Roads, roads, roads

Strong public infrastructure is another key to attracting and growing companies, local business leaders say.

The SALC, the Tucson Metro Chamber and other business groups strongly support the reauthorization of the Regional Transportation Authority, which is backed by a half-cent sales tax approved by voters in 2006 and will expire in 2026 unless it is reapproved.

The RTA was intended to fund $1.9 billion worth of projects fix shoddy roadways across Pima County, though a funding shortfall has delayed some projects.

“Infrastructure is ultimately the backbone or the spine of any economy. If you don’t have solid in infrastructure, it’s going to significantly impact your ability to do to business to create jobs, but more importantly, even to move people to and from those jobs,” Maxwell said. “Infrastructure tells a lot about a community. You can look at a community’s infrastructure and see how much they care or on the flip side, they don’t care.”

Finding people

One of the biggest threats to local long-term economic growth is not just finding qualified workers — it’s going to be finding enough people, period.

As baby boomers retire in droves and the natural birth rate declines, Tucson will see its population gains lag Phoenix and the state in the next few years, the UA’s Hammond said.

“That’s going to be a big issue, particularly for Tucson because Tucson is already experiencing negative natural increase,” he said. “That difference between birth and death for Tucson has turned from a tailwind, something that was pushing our population growth, and that’s now a headwind and we are battling against it.”

Population growth in the Tucson metropolitan statistical area, which is all of Pima County, is expected to drop from about 0.9% this year to 0.6% in 2024. Local population growth averaged about 1.5% from 2001 through 2018 and hasn’t topped 2% since 1999, according to census data.

In Tucson, as elsewhere, the tight labor market caused by people leaving jobs or retiring because of the pandemic has resulted in historically low unemployment.

But it also caused high levels of labor-market churn, and left “mountains of open jobs” unfilled, Hammond said.

A surge in defense spending most recently fueled by U.S. support for Ukraine as it tries to repel the Russian invasion has been good for Tucson’s biggest private employer, Raytheon Missiles & Defense.

But Greg Hayes, chairman and CEO of parent Raytheon Technologies, has said that labor shortages and supply-chain disruptions continue to challenge the company’s efforts to ramp up production of key weapon systems, and other defense contractors have expressed similar worries.

Raytheon, which after a major expansion a few years ago now has about 13,000 local employees, makes many of the nation’s front-line weapon systems in Tucson.

Rendering of the Leonardo Electronics US Inc. semiconductor laser manufacturing facility under construction in Oro Valley.

Attracting companies

Despite the ravages of the pandemic, Tucson seen won some major new business arrivals and expansions in recent years, including a new Amazon sorting center, a lab recently opened at the UA Tech Park by Eurofins Donor Testing Services, and a new $100 million state-of-the art semiconductor laser plant Leonardo Electronics is building in Oro Valley.

Tucson also has attracted several high-tech startups, including self-driving car developer Pony.ai and most recently, American Battery Factory.

Tucson-based Sion Power Corp. announced plans to double the size of its local operations, as it ramps up production of new, high-energy batteries for electric vehicles.

Sion, which has been developing advanced battery tech here since 1995, plans to complete an expansion to a second building on the south side by 2026, creating more more than 150 jobs, with an estimated economic impact of $341 million over five years.

The UA factor

Besides providing a pipeline of engineers and other degreed talent for Raytheon and other companies, the UA has amped up its efforts to launch companies based on technology developed by faculty and students at the school.

Since its inception in 2013, Tech Launch Arizona has helped launch 128 companies, and between 2016 and 2022, generated about 2,500 jobs and $1.6 billion in economic activity, the school says.

The UA Center for Innovation helps incubate startups with workshops, educational training and business-pitch preparation assistance at the UA Tech Park on South Rita Road and in recent years has added satellite programs in Vail, Sahuarita and Oro Valley.

Since it was formed in 2003, the UACI has directly supported a total of 235 startups that have accumulated $105.8 million in capital investment funding, with $35 million in economic impact in 2021 alone, according an report issued recently.

Small startups don’t employ a lot of people individually but the numbers add up, and there’s always the chance a homegrown startup could grow into a major employer.

UACI says its startups helped generate 441 jobs in 2021, including 182 direct, full-time positions.

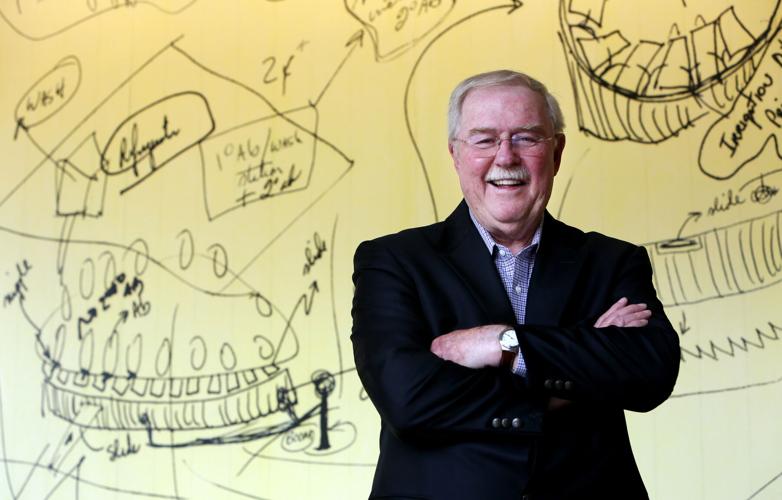

Dr. Thomas Grogan, founder of Ventana Medical Systems, Inc., shown in front of sketches that led to the automation and standardization of tissue biopsy testing.

Ventana Medical Systems was founded in 1985 based on technology invented by UA pathologist Dr. Tom Grogan for an automated instrument to prepare tissue samples for microscopic analysis.

The company went public and grew to more than 1,000 employees in Oro Valley before being acquired by Swiss drug giant Roche in 2008 in a deal worth $3.4 billion. The company has since expanded and now employs about 1,800 workers.

Team effort

Local business groups and government agencies have teamed up to lure new companies to the Tucson area.

Sun Corridor, which is mainly business-funded and is directed by a board made up of top local executives, has led efforts to win new companies and expansion projects with key partners including the Arizona Commerce Authority, Pima County, the city of Tucson and other local governments, the UA, Pima Community College and various local companies.

Known as Tucson Regional Economic Opportunities until it changed its name in 2015 to reflect a more regional scope, Sun Corridor has created an “economic blueprint” prioritizing its work in an effort to shape a high-wage, tech-based future economy.

The blueprint targets four broad industry areas to capitalize on Tucson’s strengths to attract and grow high-wage jobs: aerospace and defense; transportation and logistics; alternative energy and natural resources; and bioscience and health care.

A look ahead

Going forward, Tucson’s economy will continue to be affected by the lingering aftereffects of the pandemic, including labor shortages and supply-chain issues, as well as high inflation and high energy costs due to disruptions caused by the war in Ukraine, the UA economists say.

Worker have seen higher wages as companies compete for employees, but those income gains are more than offset by inflation, Hammond said.

And rising mortgage interest rates and low affordability already have combined to depress home sales, prices, and permit activity, Hammond said.

Looking ahead, Hammond in his most recent forecast predicts a deceleration of the state and local economies this year, even without a recession that had been forecast but has not yet materialized.

According to the UA’s economic forecast in December:

Slowing job gains are expected to drive the state’s unemployment rate up from 3.5% in 2022 to 5.2% in 2023 and 5.7% in 2024.

In the Tucson metro area, which is all of Pima County, nominal personal income growth was forecast to decelerate from 7.5% in 2021 to just 0.5% in 2022, as federal pandemic-related income support ends, then rebound to 5.1% in 2023, 5.6% in 2024 and 5.5% in 2025.

Growth in nominal retail sales (including remote sales) is forecast to drop from 11.7% in 2022 to just 1% in 2023 as negative real-income growth, declining stock and real estate values and reduced consumer confidence take their toll. Sales are expected to grow 3.4% in 2024 and 5.5% in 2025.

In the event of a nationwide recession, the downturn is expected to be less severe in Arizona than nationally, with job losses in Arizona expected to reach 0.5%, while nationwide job losses are forecast to hit 2.1%.

Further out, Hammond has forecast that through 2032 annual job growth will average 1.1%, with average annual growth rates dropping to 0.8% by 2042 and 0.6 by 2052.

Check out the recently completed Advanced Manufacturing Building at Pima Community College's Downtown Campus in Tucson.