Arizona’s water director is looking at proposals to allow some development to use groundwater in fast-growing fringes of the Phoenix area — just a month after halting new growth relying on the aquifer there.

At a meeting Tuesday of a new state committee, Arizona Department of Water Resources Director Tom Buschatzke outlined two possible changes in state rules that could allow some growth to go forward on groundwater under certain conditions.

One idea would be for a developer to “comingle” a significant amount of renewable water supplies, that don’t come from the aquifer, with groundwater.

Another would be for a developer or builder to provide assurances that some form of water infrastructure will be built to bring in another water supply that unlike groundwater is renewable.

The department also signaled it might be open to considering changes in the computerized groundwater model for the Phoenix water management area that it released June 1. The model projected the total amount of groundwater available in the Phoenix area over the next 100 years would likely fall about 4% short of expected demand. But it drew a lot of questions and unfavorable comments from water interest groups when it was unveiled.

Buschatzke also made it clear he wants tougher requirements for assured water supplies for unregulated “wildcat subdivisions.” He sees that as a way to insure that the recent saga of Rio Verde Foothills, an unregulated Scottsdale-area subdivision that has been without water since Jan. 1, won’t be repeated.

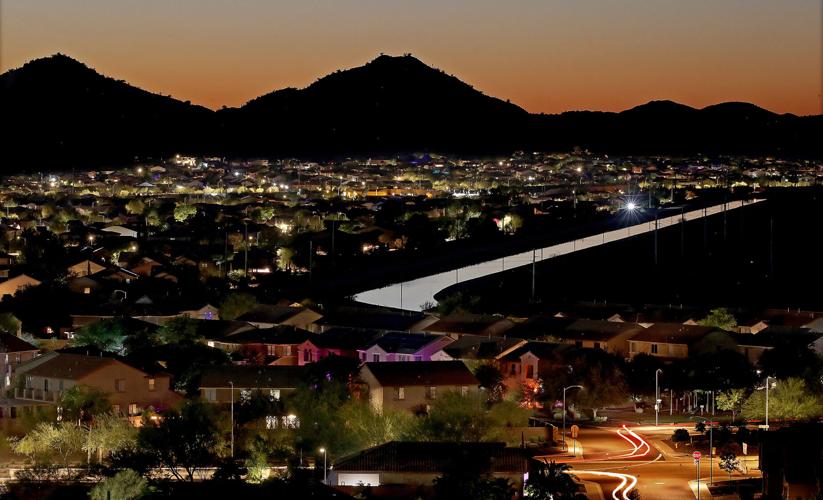

The Central Arizona Project canal in a Phoenix suburb. One idea being discussed would allow a developer there to “comingle” a significant amount of renewable water supplies that don’t come from the aquifer, such as CAP water, with groundwater.

He made these and other comments at the June 27 initial meeting of a state committee called to review state rules and laws governing assured, 100-year water supplies for new development.

On June 1, ADWR and Gov. Katie Hobbs’ announced that from now on, no new subdivision developments will be certified as having an assured water supply. That was due to a finding that the state is already oversubscribed for groundwater demands over the next 100 years compared to available supplies.

The decision doesn’t affect major Phoenix-area cities and suburbs that have their own formal state designations of an assured supply. It affects cities and private water companies operating mainly on the urban periphery that don’t have such designations. in those cases, subdivision developers must get their own state certifications of assured supply.

At Tuesday’s committee meeting, ADWR officials offered no formal proposals, but said they expect to have proposals and get others from committee members by early to mid-July. Formal proposals will need to be adopted by the committee by mid-December for consideration by the governor, state agencies like ADWR and the Legislature.

At this time, “we cannot say whether any proposals” that come out of this committee and others coming from the parent Governor’s Water Policy Council “will affect just one or all” of the state’s five water Active Management Areas, including one governing the Tucson area, said Shauna Evans, an ADWR spokeswoman.

In an ADWR slide presentation at the meeting, officials said the assured water supply program, approved as part of the 1980 groundwater law, “has enabled responsible development in an arid environment.” The program has also driven “innovation, collaboration, creativity and success in water resource management,” one ADWR slide said.

But at Tuesday’s meeting, Spencer Kamps, a committee member and a top Phoenix-area homebuilders’ official, warned the new ADWR decision limiting groundwater pumping is aggravating an already major crisis for the region’s pinched housing stock, and causing economic dislocation in the development industry.

Developers have left behind $1 billion in infrastructure improvements such as roads, sewer lines and water piping for homes that now may not be built in the Hassayampa Sub-Basin in and around Buckeye west of Phoenix, said Kamps, the Home Builders Association of Central Arizona’s deputy director.

That is one of the prime development areas for which the state has now found insufficient groundwater exists for the next 100 years.

“I don’t think we do that to any industry in this state, telling them ‘Come to Arizona and we’ll change the rules in midstream,’ “ Kamps said at the meeting. “When you are in the process of selling homes to customers, and then this home will be shut down, the impacts will be substantial. People will lose money. And the demand for housing is not going away.”

Kamps

Overall, “what I heard in this presentation today that is we’ve got to go to renewable sources,” Kamps said. “I need to tell my members what the future holds for them. If we’re going to go to renewable sources, there are none.”

‘Need to be thinking a long time ahead’

But at the same meeting, Kathleen Ferris, another committee member, a former ADWR director and now a water researcher and crusader for protecting the state’s dwindling groundwater supplies, warned that state officials aren’t addressing some major concerns about groundwater pumping even now.

She’s concerned about ADWR projections that, despite the new state limits on groundwater pumping for new homes, the overdraft of groundwater in the Phoenix area is expected to grow from 23,000 an acre-foot yearly from 2000 through 2021 to 387,000 acre-feet yearly by 2121.

“We are not going to reach safe yield. We are way far way from safe yield,” Ferris said, using a term to describe the balancing of groundwater pumping with recharge of the aquifer.

One criteria the state uses to issue findings that developers have an assured water supply is that the development’s water use is in line with the state’s management goal for that area, which is “safe yield,” she said.

“This assured water supply program is inextricably linked with the management goal. It’s really hard for me to look at them separately, especially ... when my math shows the overdraft will be 16 times greater than it’s been for the last 20 years,” Ferris said. “We are on a trajectory that is not sustainable.”

Ferris

Also unsustainable. she said, is the state’s current rule, allowing groundwater to be depleted by up to 1,000 feet in the Phoenix and Tucson areas and 1,100 feet in Pinal County if the aquifer is replenished by renewable supplies elsewhere.

“If we want to have a civilization here in 100 years, we need to be thinking for a long time ahead,” Ferris said.

But it was clear from Buschatzke’s comments at the meeting that right now, he’s more interested in dealing with shorter-term issues that can be fixed with rule changes than with longer-term issues.

Kamps, for instance, said, “We need a very, very short-term offramp to keep these projects afloat and deal with a housing demand crisis.”

Since developers of subdivisions, unlike developers of all other projects, are required to replenish the aquifer with the amount of water that they pump, “Why are we the only projects stopped? Why can we not continue to grow on groundwater?” he asked.

Buschatzke told him, “I would ask you to draft a proposal that captures the concepts you just talked about for our consideration. Let’s move on.”

But when Ferris and committee member state Sen. Priya Sundareshan brought up other issues requiring longer-term solutions, Buschatzke said those may well have to wait.

Sundareshan, a Tucson Democrat, asked, for instance, why the state doesn’t require all forms of development, not just subdivisions, to prove they have a 100-year assured water supply.

Sundareshan

She also criticized a common practice by many subdivision developers of pumping groundwater near their projects but replenishing the aquifer elsewhere, saying, “That has not necessarily been looked at as the best idea.”

Buschatzke told her, “Those are very broad issues, getting at the basic underpinnings of the groundwater code — the deal that was made back then” in 1980, when Arizona’s Groundwater Management Act was enacted.

“I’m not saying they aren’t important to address. (But) hopefully, we’re wanting to focus between now and December, some flexibilities, focusing on allowing development to come forward, new subdivisions to move forward,” under the new assured water supply limits the state has just instituted, he said.

If progress is made on some of the immediate issues by December, that will help officials shift to the additional issues that Ferris and Sundareshan have brought up “at least at the start of the next calendar year,” Buschatzke said.

‘Wildcat’ subdivisions a problem

The Assured Water Supply Committee is part of the new State Water Policy Council that Gov. Katie Hobbs established upon taking office in January. The committee’s task is to identify ways to strengthen the Assured Water Supply program and allow for growth based on other water supplies besides groundwater, ADWR has said.

The first challenge Buschatzke wants to tackle is the problems of “wildcat” developments of five or fewer homes that, because they aren’t legal subdivisions, don’t have to prove they have an assured, 100-year water supply.

Rio Verde Foothills, an unregulated subdivision outside Scottsdale that’s gone without water since Jan. 1, apparently will be getting water again soon under a compromise bill that Hobbs signed into law about two weeks ago. It will create a new kind of government entity to deliver water to the unincorporated community.

But just the presence of such subdivisions that lack guarantees of water “exacerbates groundwater mining, puts homeowners at risks and feeds a negative perception about Arizona’s ability to manage its water supplies,” Buschatzke said.

He wants a requirement that any new community of one or more detached units can’t get building permits without obtaining a state assured water supply certificate. Such a requirement would also apply to “build to rent” subdivisions that build homes only for rental purposes as a way of escaping the state’s assured water supply rules for for-sale housing subdivisions.

Changes being weighed

The “comingling” proposal being floated by ADWR seeks to get around existing state law that limits a subdivider’s ability to deliver renewable supplies to a local water system if that system also uses groundwater.

As the law stands, a development that would use renewable supplies such as Central Arizona Project water from the Colorado River can’t proceed unless it can show it also has enough groundwater to last for 100 years.

Buschazke’s proposal, still in its early stages, would allow “comingling” of groundwater and renewable supplies if a developer brings in at least as much renewable supply as he would serve to customers with groundwater, plus a lot more.

Besides CAP, other water supplies that could be comingled with local native groundwater might include treated sewage effluent, desalinated water, non-CAP Colorado River water transferred to the Phoenix area, and groundwater imported from the Harquahala Valley in Western Maricopa County.

The third proposal, regarding infrastructure, follows up on a practice that the state encouraged during the 1980s and 1990s as the 336-mile-long CAP canal system was gradually built from the Colorado River to Phoenix and Tucson. While that construction proceeded, a new development whose owner had a CAP allocation or a water contract would be assumed to have an assured water supply even while using groundwater, until the $4 billion project was finished.

The new proposal would allow development to proceed on groundwater while the developer was pursuing an alternative, renewable water supply. The developer would have to meet requirements for things like a five-year construction plan for the renewable water system, financial assurances and the like.

The water system would have to meet a series of legal milestones for completing such tasks. Its assured water supply certificate from the state would expire if the development didn’t meet those milestones.

“We all could probably agree that the nature of those supplies for cities with CAP allocations has worked really well,” Buschatzke said at the meeting. “The development has occurred. We haven’t seen the infrastructure not be built.”

Doug Dunham, water resources manager for a major private water company that’s active in Phoenix, Epcor, told the meeting that he appreciates some of the proposals put forward by Buschtzke. His company has CAP water supplies and effluent it could put to use for new developments if the comingling “roadblock” were eased, he said. Dunham is also a member of the new Assured Water Supply Committee.

Queen Creek is one of the fast-growing areas in the greater Phoenix metro area where water supplies are an issue.

The infrastructure proposal could also be useful for his company’s water system because it employs a similar system today for securing approval of new supplies to meet Arizona Corporation Commission requirements for private water companies, he said.

“Thank you for coming forward with these proposals,” said another committee member, Cheryl Lombard, president and CEO of Valley Partnership, a Phoenix group that promotes what it calls responsible development.

“The infrastructure proposal is especially encouraging and very important to our members,” Lombard said.

Skeptic calls out abrupt change

Former ADWR director Ferris is skeptical of both proposals.

She noted that when former Gov. Doug Ducey had a water advisory council in 2021, “a bunch of people in Pinal County were saying that you have to get rid of this” rule against comingling. “ADWR said then, that doing that would erode the consumer protection provisions of the assured water supply requirement.

“Now the DWR has a proposal that’s quite unclear to me. It looks like they will support this (comingling) as long as the developer or whoever brings in the extra source, brings double the amount of what the subdivision needs. I’m not sure why the department now thinks this idea is OK when before they didn’t.”

As for the infrastructure proposal, Ferris noted that when a similar system was in place for the CAP back in the 1980s and 1990s, that project had already been federally authorized and money appropriated every year for its construction.

Now, under the new proposal, until some certainty exists that “all these pieces are falling into place” for a new water project, what’s going to happen to a new development counting on water from an unbuilt project, she asked.

“Is the ADWR going to be issuing certificates of assured supply that will just sit idle, based on future construction of infrastructure? Or will ADWR issue certificates that allow groundwater to be pumped in the interim?”

“When I look at this, the issue is clear that more must be done, but the response from ADWR is to allow some development to move forward on groundwater,” she said.

Longtime Arizona Daily Star reporter Tony Davis talks about the viability of seawater desalination and wastewater treatment as alternatives to reliance on the Colorado River.