At least 40 proposals that would make it easier or harder for developers and water users to prove the existence of an assured 100-year water supply confronts a state advisory committee representing a wide array of interests.

Some proposals would at least slightly open the doors to development in areas near Phoenix that were recently closed. The state’s action last month to limit new growth supported by groundwater there was accompanied by the release of a computer model report finding that the entire area faces a shortfall in groundwater supplies compared to demand over the next century.

Other proposals would tighten the reins on development based on groundwater use, out of concern the state’s new limits may not prove adequate.

While the proposals are in part a reaction to the Phoenix-area development issue, several sources said they could also affect the Tucson area and other urban areas that are covered by a 43-year-old state requirement for new subdivisions to show an assured 100-year water supply.

One proposal would allow development to occur on the use of groundwater if the developer can demonstrate that the project will have access to a renewable, non-groundwater supply in a fixed time. Another would change how the Arizona Department of Water Resources does its computer modeling in ways that could potentially show a less problematic outcome for new growth by indicating that future demand will be less than currently projected.

A third proposal would make it easier for developers and perhaps water providers to “commingle” renewable supplies such as Central Arizona Project water with groundwater before serving the water to customers.

But a proposal that would make it harder to prove an assured supply would reduce the maximum depth to which development could cause water tables to decline. Another would require all new industries and other businesses to prove that they have assured water supplies — a requirement now limited to subdivisions.

Another would require proof of assured water supplies for development anywhere in the state. This requirement now covers only five, mostly urban, state-run water “active management areas.” Still another proposal would require new subdivisions that use pumped groundwater to recharge renewable supplies into the same aquifer from which they pump.

The proposals come slightly more than a month after the Arizona Department of Water Resources released its report that the greater Phoenix area will have a nearly 5 million acre-foot-a-year deficit in groundwater supplies compared to demand over the next 100 years.

Because of that finding, ADWR stopped issuing certificates of assured water supplies for new developments that rely solely on groundwater. The decision will limit future homebuilding on the periphery of the Phoenix area, although not in Phoenix itself. ADWR has already issued similar curbs on homebuilding in much of Pinal County following a similar finding of inadequate groundwater supplies.

The proposals come from state agency officials, lobbying groups, legislators and individuals and groups representing developers, city water utilities and private water companies.

All of them sit on an Assured Supply Committee, whose members were chosen by Democratic Gov. Katie Hobbs. Its purpose is to determine if changes are needed in the state law and rules governing assured supplies. The committee is supposed to make recommendations to a larger Water Policy Council, also created by the governor, by year’s end.

Republican Rep. Gail Griffin of Hereford, a committee member, has blocked legislative measures that would have tightened up or enacted various groundwater protections that she said would violate private property rights.

The members have a wide range of outlooks. At one end of the spectrum is state Rep. Gail Griffin, a Hereford Republican and a fervent advocate of private property rights who opposes regulations she sees as infringing on people’s right to live or start a business where they choose. More than once, Griffin has blocked legislative measures that would have tightened up or instituted various groundwater protections that she said would violate property rights, particularly in rural areas where no rules regulate pumping at all.

At the other end is Kathleen Ferris, an attorney, water researcher and former ADWR director who has crusaded for more than four decades with some success to try to ensure that new growth doesn’t drain the state’s diminished aquifers.

Other members include state Tucson Democratic state Sen. Priya Sundareshan, officials of water user groups from the Tucson and Phoenix areas, officials of Tucson Water and the Phoenix Water Department, two Hobbs cabinet members, a private water company official, a Pinal County water agency, and representatives of two development interest groups. Top officials of the three-county Central Arizona Project and the Phoenix-based Salt River Project also sit on the committee.

While ADWR presented some of the proposals at meetings of the committee and a related subcommittee, none of the proposals has the endorsement of that agency or the governor’s office, said Christian Slater, Hobbs’ communications director.

The committee’s formal objective is to “review and make recommendations” for updates to state assured water supply policies “to address challenges revealed by the modeling projections” for the Phoenix area.

“But as a matter of policy, ADWR likes all the (active management areas) to have the same policy,” said Spencer Kamps, a committee member and a vice president and lobbyist for the Home Builders Association of Central Arizona. “So this question has not been discussed by the water council as far as I know, and is unsettled,” he said, referring to whether the committee’s work could apply to all active management areas, including Tucson.

Sarah Porter, director of Arizona State University’s Kyl Center for Water Policy, sees clear, possible implications in these proposals for other urban areas, including Tucson.

“Everybody understands that Pinal County is under the same limit as Phoenix. It’s also a place with a lot of pressure for more growth,” said Porter, who isn’t a committee member. “As (ADWR Director) Tom Buschatzke has said, we have been allocating groundwater for 40 years in these areas, and pretty soon, unmet demand for it will daylight in all of them.”

‘Who gets to decide?’

The potential for controversy over the assured water supply issue springs first from the very principles that the state water agency is espousing for how changes to the law and rules should be considered.

ADWR has said proposals:

Must protect the strength and integrity of the Assured Water Supply program.

Should enable future growth without reliance on mined groundwater.

May not reduce the 100-year requirement or increase the depth to which groundwater may be pumped.

Must ensure there is water before growth.

Must protect consumers.

In a July 7 letter to Buschatzke, however, legislator Griffin strongly objected to the ADWR’s having made these principles preconditions for any proposal to be formally considered.

The principles “create a clear, anchoring bias that favors one viewpoint over others and precludes the committee from considering other, potentially new and innovative ideas if they do not go along with preconceived notions,” said Griffin, who chairs the House Natural Resources, Energy and Water Committee.

“As a state lawmaker and elected representative for over 15 years, I understand that successful adoption of complex policies is rarely accomplished through the unilateral demarcation of terms, but rather through the collaborative process where shared values and principles can be developed organically from the people,” Griffin wrote.

“Where did these ‘principles’ come from? Who developed them? And why weren’t they brought to our attention before their adoption?” Griffin wrote. “Who gets to decide which proposals are ‘consistent’ with the purported principles? Is it the Director of ADWR; and if so, then why is it not the collective members of the (Assured Water Supply) Committee?”

One principle she felt should have been on ADWR’s list is that groundwater savings and other benefits to the assured water program should be achieved through voluntary efforts rather than government mandates. Voluntary conservation by commercial and industrial development will be key to reducing the amount of unmet groundwater demand, she wrote.

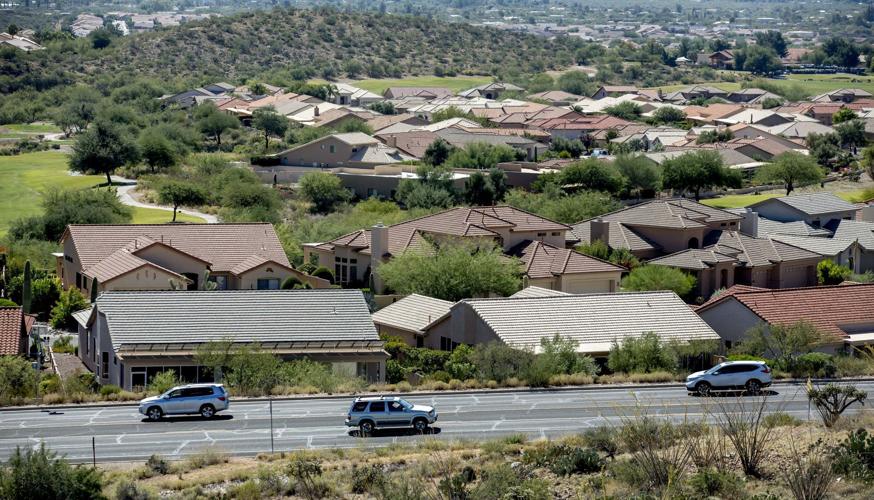

SaddleBrooke in Pinal County, north of Tucson, is one of the areas in Arizona that use only groundwater.

“Most importantly, I believe in the protection of private property rights and individual liberty, and that the right to be self-reliant, live off the land, and build a home or start a business in the location of one’s choosing — free from government interference—should not be infringed. This has been a guiding principle for most of my years in public service, and I believe that the committee should not be allowed to consider any proposal that would interfere with these rights,” she wrote.

For Ferris, however, ADWR’s principles are bottom-line, core concepts — “guiding stars” — that must be adhered to in changing any law or rule. She has opposed for years any state law or rule changes that she felt would accelerate the “mining” of groundwater by pumping out more than is replenished by rainfall and through artificial recharge efforts.

Her concern — shared by many professional hydrologists — is that overpumping will trigger land subsidence, raise pumping costs and worsen the groundwater’s quality.

Ferris declined last week to take a stand on the latest set of proposals, saying she needed to review them further. But she vowed to fight any proposal that will allow additional development that relies on the use of groundwater.

ADWR’s principles are “just common sense,” said Ferris, a researcher for ASU’s Kyl Center and a former director and legal counsel for the Phoenix-based Arizona Municipal Water Users Association.

“ADWR’s models predict that groundwater in storage in the Phoenix Active Management Area will decline substantially over the next 100 years — and with CAP cuts and climate change, the decline will be even worse. We cannot keep relying on mined groundwater as a source of water for growth if our state is to maintain our economies, our beautiful environment and our envied way of life,” she said.

Despite these and other clear differences of views among committee members, ASU’s Porter said she sees potential avenues for compromise.

“I have talked to people who are interested in seeing some ways of allowing some development beyond what’s already permitted,” by certificates of assured supplies for new developments, said Porter, who declined to identify them. “But they understand in order to get there, the assured water supply program needs to be strengthened.”

The recent limit on new development in the Phoenix area, along with the creation last year of a new Active Management Area in the Douglas area and state restrictions on new farming in northwest Arizona, are all “winds of change” that may lead people now “to find solutions that involve give and take, and I really mean that,” said Porter.

Potentially controversial examples

Some of the most sweeping and potentially controversial proposals before the committee are:

1. COMMINGLING. One that would make it easier for developers and possibly water utilities to “commingle” renewable supplies such as CAP water with non-renewable groundwater to be served to homes and businesses. The current state rule requires a water provider or developer to show that the groundwater supply is adequate even though they intend to bring in a renewable supply. This is to protect homeowners from facing the risks of groundwater shortages, the agency says.

The proposal would require a developer who brings in an alternative water supply to secure a separate, equivalent amount of renewable water to give to the water provider. This step is supposed to create an incentive to bring in renewable supplies.

In a separate proposal, committee member Doug Dunham, an executive with private water company Epcor, called for allowing a water provider to bring in the renewable supply along with the developer and spelled out that use of treated sewage effluent would be allowed.

The Central Arizona Project aqueduct system that brings water from the Colorado River is one major source of renewable water, but the river is shrinking.

2. INFRASTRUCTURE. Typically, state rules don’t allow developers to use groundwater for their projects on the basis that they will bring in renewable supplies in the future. ADWR is floating a proposal to allow that if a developer provides milestones for completion of pipes and other infrastructure for such a project and agrees that the project’s assured supply certificate would expire if the milestones aren’t met.

The developer would also have to post a performance bond to ensure that money for the infrastructure would be available and show that he has permits for construction of the project.

Dunham proposed to allow an “interim water supply” — which he doesn’t identify — to be used “if appropriate supplies and infrastructure are available within 20 years.”

3. COMMERCIAL AND INDUSTRIAL DEVELOPMENT. Stores, malls and industrial plants aren’t covered by assured water supply rules unless they’re part of a legal subdivision. But several committee members want to look at possibly placing them under the rules because otherwise, their pumping can contribute to groundwater overdraft.

Ferris and Sundareshan want the committee to either recommend or consider recommending putting such projects into the Assured Water Supply program. That would require them to prove, as homebuilders now have to prove, that they have an assured, 100-year supply.

Kathleen Ferris wants the committee to consider requiring stores, malls and industrial plants to prove, as homebuilders now have to prove, that they have an assured 100-year water supply.

Epcor’s Dunham would approach the issue differently. He would require that a business developer show that the project’s water demand “will not negatively impact” existing water uses that have already met the assured supply rules. A new industrial user would have to make 50% of its groundwater demand consistent with the urban area’s management goal for groundwater supplies.

4. WATER LEVEL DECLINES, REPLENISHMENT RULES. Today, developments can draw down aquifers by 1,000 feet and comply with the state rules in the Tucson and Phoenix areas and by 1,100 feet in most of Pinal County. Ferris proposes to reduce that to 800 feet deep, to reduce long-term risks of the aquifer suffering from subsidence, in which it compacts and ultimately collapses. Such a restriction would make it harder to prove a development has an assured supply and would undoubtedly draw strong opposition.

Ferris and Sundareshan also want to require developers who build new subdivisions relying on pumped groundwater to replenish the aquifer in the same areas where the pumping occurs with renewable supplies. Today, there’s no requirement as to where the recharge of CAP water from the Colorado River and other renewable supplies can occur other than it must happen within the same Active Management Area where the development’s groundwater is pumped.

Critics of the current practice say it triggers local depletion of aquifers. Supporters of it say the overall groundwater basin remains sustainable because of the recharge.

5. DEVELOPMENT FEES. Dunham and Cheryl Lombard, president and CEO of a Phoenix-based development group, advocated for charging development fees on new projects to help pay for new water supplies and for other ways to reduce the amount of demand for groundwater that’s not met by existing supplies.

The fees could pay for new water supplies and support agricultural conservation programs to improve farms’ water use efficiency. It could also pay for water users to connect their systems to other systems whose water supplies are less problematic.

6. NON-REGULATORY TOOLS. Griffin’s letter to ADWR essentially spoke out against the department’s recent limits on Phoenix-area subdividing. All new businesses and people to the state should be welcome, she said, whether they choose to locate inside areas served by utilities with assured supply designations — which weren’t affected by the ADWR limits — or outside them in areas where growth has now been curbed.

“I also believe that no proposal should be allowed to shut down our state’s economy or preclude growth outside of designated providers if the growth can demonstrate minimal impact to the groundwater table,” she wrote. The use of effluent and the replenishment of aquifers should be considered in future groundwater studies, Griffin said. Water providers with designations or certificates should be able to submit data showing their customers are using less water, she added.

For the most part, she advocated voluntary conservation measures and incentives rather than mandates. The state should encourage development that doesn’t affect groundwater tables and set up a committee to establish “best management practices” for commercial and industrial businesses, she wrote. If water providers with state-approved certificates or designations of assured supply see reduced water demand, the ADWR should allow them to take credit for that in its groundwater models, she said.

She did endorse requirements for developers of “build to rent housing,” which is now exempt from the assured supply rules, to replenish aquifers with renewable supplies and for commercial and industrial projects to reuse their wastewater at their sites, however.

7. FARMS TO HOMES. Since farms typically use far more water than homes and businesses, proposals to encourage the replacement of farms with subdivisions drew support from unlikely allies: Ferris, Epcor’s Dunham and homebuilder lobbyist Kamps. Dunham suggested creating a ‘hybrid” assured supply water designation for lands lying within irrigation districts. Ferris advocated a “more sophisticated mechanism,” unspecified, to channel urban growth toward farmlands.

Get your morning recap of today's local news and read the full stories here: http://tucne.ws/morning