Bright pink blobs punctuate every corner of the state in a map produced by the Arizona Department of Water Resources. They show groundwater aquifers falling, often rapidly, in many if not most rural areas of the state, from the Willcox Basin on the southeast, to the Gila Bend Basin to the Southwest, to the Hualapai Basin to the northwest near Kingman.

These declines have been chronic statewide and are generally agreed to be getting worse, largely because of increasing levels of unregulated and unmonitored groundwater pumping. In the five most critically impaired groundwater basins, including the Willcox Basin southeast of Tucson, the state agency measured water levels in a series of what it calls “index wells” and “we had declines in every single well,” ADWR Director Tom Buschatzke told the Star.

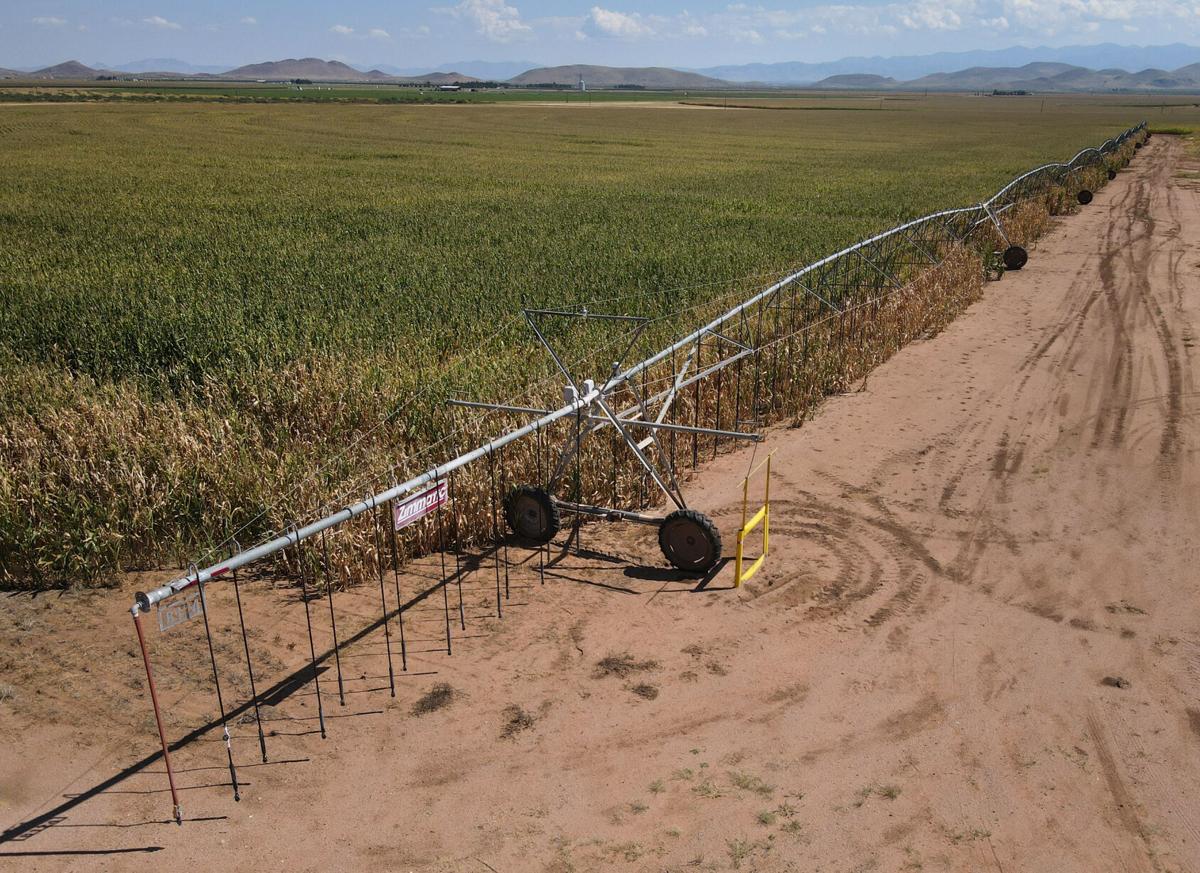

Much if not most of that pumping is for farming, and many of those farms are of the large, corporate variety run by out-of-state and in some cases out-of-U.S. companies. For years, scientists and other experts have warned that aquifers in rural areas from Willcox to Kingman are imperiled by pumping far exceeding what Mother Nature puts back into the ground.

These facts form the backdrop for a debate over rural groundwater use that has proven irreconcilable for years. It pits conservative, rural community leaders not just against urban environmentalists but against one another.

Twelve county supervisors from around the state, for instance, have signed a letter opposing a proposed plan to control rural groundwater pumping made by a water policy council appointed by Democratic Gov. Katie Hobbs. Four other county supervisors have issued a news release supporting it. Many farming interest groups are fighting that measure but some are supporting it. The Kingman Chamber of Commerce just issued a statement supporting the council’s proposal.

Now, the new set of proposed state rules for managing rural groundwater from the water policy group would offer a path toward more sustainable rural economies, its backers say. Or, it could destroy the fiber of rural communities whose economy depends on farming, say its opponents.

It may simply solidify the stalemate over rural groundwater regulation that has persisted in Arizona since at least the early 2010s, during which time legislation to bring more water regulation to rural areas has repeatedly died. Or, it could lead to a compromise.

While both factions disagree on the solutions, they agree Arizona’s rural groundwater supplies are at risk from over-pumping.

“Absolutely, something has to be done,” said Jamie Rohner, executive director of the Arizona Cotton Growers Association. “That’s really, really challenging. Everybody’s going to have to make some kind of sacrifice. There’s going to have to be give and take.

“But I don’t think this proposal really took input from rural communities. Their input was never solicited,” Rohner said.

The fact that everyone recognizes there’s a problem shows progress has been made, said Haley Paul, Arizona policy director for Audubon Southwest.

“I feel like five years ago there wasn’t that consensus. Now certain parts of the state are facing drastic reductions in their groundwater supplies. They need help,” Paul said. “The question is, will we be able to come together and pass a bill that protects their water future, gives them a little more certainty, gives them more protection?”

New recommendations

Now at issue is a proposal for Rural Groundwater Management Areas recommended almost unanimously Wednesday, Nov. 29, by the 37-member, State Water Policy Council convened by Hobbs earlier this year. The council’s recommendation came after months of discussion by a smaller committee.

Rural communities would be allowed to establish governing councils to manage and regulate groundwater pumping in their areas, under the proposal. The decision to designate such councils would rest with the state but locals would run them and could petition the state to create them.

It is a tougher and stricter proposal than those tried and failed in past Arizona Legislatures. For the first time, this scheme would require any new rural groundwater plan to require mandatory conservation efforts.

It also for the first time would require mandatory monitoring and metering of water use by individual wells using more than 35 gallons per minute. Also new is a proposal to require that any new wells drilled in these areas be spaced far enough apart to minimize risks their pumping would dry up neighboring wells.

One of the more vocal backers of this proposal on the water council is Ed Curry, a chili and seed grower in the tiny community of Pearce at the west end of the Willcox Basin. Its recent, worsening declines in groundwater levels in the face of massive new agricultural pumping has brought it national attention.

“I have skin in the game; I got 2,000 acres of farmland. I’ve used some very innovative crops — I can’t really say what they are — some very low-water-use crops,” said Curry, a lifelong Cochise County resident who has farmed the area for more than 50 years.

He is concerned that if this proposal doesn’t pass, Hobbs and/or Buschatzke will create a much stricter, state-run Active Management Area for the Willcox Basin.

That idea — which Willcox Basin voters overwhelmingly rejected in a 2022 referendum — scares Curry because in one, farmers are granted “grandfathered” rights to use groundwater based on what they used over the previous five years. Because Curry has emphasized low-water-use crops so heavily in the past eight to nine years, he feels he would be penalized in planning his future use, he told the Star.

“Those that have double cropped, people who have crops that use high amounts of water, especially those who are abusing the situation, they will win. Here I was trying to save the damn valley. I was trying to save water to help our side of the valley by finding these low-water-use crops, and the AMA was going to hurt me and reward the guy that was abusing the situation,” Curry said.

“We will come up with a different way to establish historical water use; we will probably ask for a set amount of water right within our district,” he said.

“None of us are asking for extreme water rights,” added Curry, noting that his father back in the 1960s and ‘70s helped put into effect a state-run Irrigation Non-Expansion Area for the Douglas Basin south of the Willcox Basin. In such areas, no new agriculture is permitted.

“Our family is very pro ‘let’s be wise with our water.’ But also ‘let’s don’t be penalized because we early on were seeking to use less water,’” he said.

“An old clunker idea”

But to the cotton growers’ Rohner and to Stefanie Smallhouse, president of the Arizona Farm Bureau, this proposal is just a warmed-over version of earlier, failed proposals.

“They basically resurrected an old clunker idea, with two flat tires and bad gas, where they’re going to try to limp it to the Capitol and call it a Maserati,” said Smallhouse, a former Governor’s Water Policy Council member who quit in October to protest what she said was many members’ unwillingness to take input from rural communities. Her family farms in the Lower San Pedro River Valley near Redington, on land in Pima and three other counties.

“It was a predetermined report from an urban dominated group that is making choices for rural Arizona,” said the cotton growers’ Rohner. “They didn’t entertain all of the proposals. Different frameworks, different ideas, they were never heard by the committee or the Water Policy Council.”

The latest is a refined version of what conservation advocates called Local Groundwater Stewardship Areas. Placing local community members on the councils that govern these areas would enable local control, the plan's advocates have said.

"Our constituents, business communities, neighbors, friends, and family members have watched their aquifer levels substantially drop, lands and roads collapse or crack due to land subsidence, and future rural generations’ livelihoods jeopardized," said a Nov. 29 letter from four rural county supervisors in support of the rural groundwater plan proposal. "Rural Arizona can no longer afford inaction on this issue of rural groundwater sustainability that jeopardizes our citizens, our businesses, and our regional economies."

But in a Nov. 1 letter to Gov. Hobbs, a group of 60 persons, farm-related companies, agricultural interest groups and legislators said this proposal would diminish existing farm access to water without providing certainty for current or future groundwater rights.

"It is also clear that the creation, planning, and goal-setting components of the (stewardship areas) denies local stakeholders the opportunity to determine how best to manage their water resources," instead employing "the equivalent of a super water and land use board, empowering the Governor and the DWR Director to dictate to rural Arizona water users," that letter said.

There are three major sticking points separating the water Policy Council proposal from an alternative measure floated by state Sen. Sine Kerr, a Republican who quit the council along with Smallhouse.

Stefanie Smallhouse, president of the Arizona Farm Bureau

Kerr’s proposal would have established a water right for farmers who historically operated in an area before the new rural groundwater management scheme took effect.

“It means protecting the existing uses in a way that people have certainty that their water is not going to be taken away for a municipality,” Smallhouse said.

Such rights would be similar to grandfathered water rights that farmers and other historic users get in urban water management areas, but should have different elements for rural areas, she said.

But the Water Policy Council’s proposal would call for “acknowledgment” of existing uses in new Rural Groundwater Management Areas, without awarding the users legal water rights and subjecting the existing uses to future conservation requirements.

“The idea was ‘let’s recognize people who are already there,’” Audubon’s Paul said.

“That gets kind of tricky. We were trying to thread the needle between acknowledging those who are there, and not making it like an Active Management Area, where you are assigned a grandfathered right.”

Water council members and ADWR officials were “perfectly fine” with creating a water right reflecting historic use, “but what we couldn’t agree to was an outcome in which a water right can never be reduced with efficiencies or conservation,” said ADWR’s Buschatzke.

Mandatory conservation

A second sticking point is the policy council’s requirement for mandatory conservation in the rural water management areas. Kerr’s proposal had a general provision for regulations but said nothing about mandatory conservation. Republican State Rep. Gale Griffin, who chairs the House Energy and Natural Resources Committee, also said she wouldn’t back such a proposal.

Smallhouse said a rural management scheme should first offer incentives for conserving before resorting to mandatory measures. Rohner said she’s not opposed to mandatory conservation but added, “My fist question is, what is its purpose? I think it’s something bigger underneath. Agriculture has been working to conserve water. I’m a little bit new to the world of politics, (but) as I’ve gone through this process; I think there’s something that’s driving it.”

But “ultimately, the council decided that’s pretty essential if we’re going to get groundwater pumping under some control so we can protect existing users,” Audubon’s Paul said of mandatory conservation.

Chile farmer Curry said of mandatory conservation. "If we’re not going to be requiring conservation, how robust can these things actually be? If we're going to go through this effort to manage groundwater, we need to manage it."

Finally, the Water Policy Council proposal calls for appointing members of the governing bodies for the Rural Groundwater Management Areas, although council members didn’t decide whether ADWR, legislators or county supervisors should do the appointing. The farm bureau, cotton growers and other agricultural interest groups want the governing body members to be elected by local residents.

“It’s better to have a locally elected board, where you have ADWR still putting in their input, and having some kind of oversight to say you need a second look at this,” said Buster Johnson, a Mohave County supervisor who opposes the policy council plan. “I don’t like somebody from some place else, where you don’t even know who they are, having control over your water.”

Another Mohave County supervisor who supports the policy council plan, Travis Lingenfelter, said, “The last thing I believe rural Arizonans need is to have these people get onto this new entity, to expand government, when you’ve not got the level of expertise and education you need if it just becomes a political popularity contest.” He serves on the council as an alternate member.

Legislation vs. governor acting

Griffin has bottled up similar legislation in her House Natural Resources, Energy and Water Committee for years. She has essentially threatened to do that again. She was the only remaining member of the Water Policy Council to oppose its rural groundwater management proposal. Besides mandatory conservation, she took exception to mandatory metering of water use, limits on new well drilling or provisions forbidding large water users from expanding their pumping.

She supported several of Kerr’s less restrictive measures, along with “protections for private property rights in the land and in the groundwater beneath the surface estate.” Water conservation should be encouraged, not mandated, by investing in water recharge projects, capturing stormwater runoff and installing “xeriscape” landscaping, she said.

Plus, “any goals that are adopted or advanced should include or be explicitly limited by” state constitutional provisions saying “all power is inherent in the people,” and that governments derive their authority from “consent of the governed,” she wrote.

Already, a Democratic representative on the water policy council, Stacey Travers of Tempe, says she doesn’t expect the committee’s proposal to be enacted “until there is a new committee chair.”

“As legislators we need to be thoughtful in our legislation … part of what you do, especially what you do in a minority party, is prepare yourself in terms of policy for what you can imagine for the future,” Travers said.

Rep. Gail Griffin, R-Hereford, has power over water legislation as a key committee chair.

ADWR’s Buschatzke, however, said that once more details are addressed in the council’s plan, “I expect we will build broad levels of support that we can bring forward to multiple legislators, hopefully in a bipartisan way, and see where it goes from there.”

The farm bureau’s Smallhouse and the cotton growers’ Rohner said they’re working on a counter-proposal to be introduced as legislation.

“There has been a lot of work in rural areas to feverishly come up with a proposal that fits the needs of rural communities. I think there will be a completely different idea to come forward,” Rohner said.

While Hobbs put a timeline on her council’s work, “we’re not putting a timeline on our work,” Smallhouse said.

Curry, however, said he thinks he can negotiate a compromise with Griffin, whom he called “a very good friend” and “a wonderful person who practices American values.”

The chili farmer joined the Water Policy Council in October after Kerr and Smallhouse quit, and felt his job was to come in and bring the two sides together.

“We had the far right and the far left. The far right is afraid of the environmentalists, afraid of everything. The far left has its own fears of the far right, that the far right is going to suck the valley dry.”

As for Griffin, he said, “I love Gail. She’s helped me in my life a lot. I have great faith in Gail. We can work this out with God’s help.”

If legislation doesn’t pass this year, the creation of state-run Active Management Areas in rural Arizona — a solution both sides say they don’t want — may be inevitable. If necessary, Hobbs would seriously consider creating them administratively for some of the basins with the worst groundwater declines, said a spokeswoman for the governor, Sophia Solis.

Get your morning recap of today's local news and read the full stories here: tucne.ws/morning