The Eagle landed, but this Falcon is going to crash.

Part of the Space X Falcon 9 rocket launched in 2015 is now on a collision course with the moon, and a team of University of Arizona researchers is trying to figure out exactly where the impact will occur on March 4.

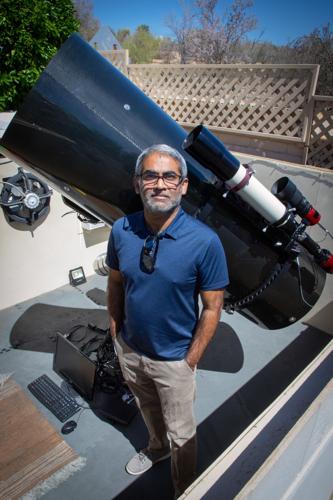

“This thing is big,” said Vishnu Reddy, an associate professor with the UA’s Lunar and Planetary Laboratory who helps the U.S. Air Force track satellites and space junk. “It’s 46 feet long, 13 feet wide and weighs about 8,600 pounds.”

The second-stage booster has been making wide arcs around the Earth since it was launched on Feb. 11, 2015, to deploy the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Deep Space Climate Observatory, an early-warning satellite for solar magnetic storms.

Elon Musk’s space transportation company designed its Falcon 9 with a reusable first stage that returns to Earth after launch and lands upright on a floating barge. The rocket’s upper stage usually falls back into the atmosphere and burns up, but in this case the payload needed an extra boost to deliver NOAA’s climate observatory to an orbit about a million miles from Earth.

Astronomer Bill Gray is credited with tracking the wayward booster and determining when it would hit the moon.

Reddy said Gray, who designs astronomical software under the name Project Pluto, is a “close collaborator” for the same satellite surveillance program the university is involved in to help the Air Force maintain what is known as “space situational awareness.”

UA doctoral candidates Adam Battle and Tanner Campbell and undergraduate engineering student Grace Halferty are now using observational data to narrow down the Falcon 9’s expected impact site.

The tumbling booster isn’t visible with the naked eye, but Reddy and his students were able to observe it through a telescope last month.

A video captured in January by researchers at the University of Arizona shows a SpaceX Falcon 9 second stage booster tumbling in space (moving dot in the middle).

The booster from a 2015 launch will hit the far side of the moon on March 4. Video courtesy of Vishnu Reddy.

They plan to watch it again on Monday, Feb. 7, from the roof of the UA’s Kuiper Building using RAPTORS, a telescope system built to spot space junk.

Reddy said the booster should be in their field of vision from just after sunset until about 10 p.m. as it makes its final pass by Earth, and the longer they track it, the better sense they will get of its precise trajectory and where on the moon it will land.

They will also study the Falcon 9’s spectral properties as it passes overhead.

“It’s not some fun class project,” Reddy said. “It’s an operational thing. We’re doing this for the Air Force.”

According to projections by Gray and others, the 4-ton piece of space junk will hit somewhere on the far side of the moon — the part that always faces away from us — at just after 5:25 a.m. March 4.

Reddy said no one on Earth will get to see the actual impact, but he is hoping NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter will be able to get some detailed, before-and-after pictures to see what kind of damage it does.

The orbiter’s camera is operated by a team led by professor Mark Robinson at Arizona State University’s School of Earth and Space Exploration.

Next month’s cosmic collision represents something of an unfortunate first for humankind. Never before have we launched something into space, only to have it accidentally crash land on another world.

We’ve already surrounded our planet with tens of thousands of dead satellites and other pieces of orbiting debris, Reddy said. “Now we’ve junk from Earth hitting the moon.”