The car coming toward Julia Lehman looked like it was flying.

The wildlife rescue volunteer had just left a McDonald’s parking lot where she had met with someone to retrieve an injured hawk. She considered going inside to grab lunch but decided she better get back to Tucson — the hawk was not in great shape.

She drove toward the highway and got in the left turn lane, at Whetstone Commerce Drive and SR 90 in Benson, behind a semi. The semi moved and she saw the Ford Expedition flying at her. It looked like it was trailing smoke.

“The next thought was, this is gonna hit me,” Lehman said. “There’s no way I can avoid this, and at the same time I just kind of thought, this is it. I thought for sure I was going to die.”

The Expedition crashed into her GMC Yukon at an estimated 100 miles an hour. A Border Patrol vehicle and Benson police, sirens blaring, were not far behind.

It was only later that Lehman found out her crash was part of a suspected human smuggling incident. Criminal organizations are hiring U.S. citizens, often young people they find on social media, to pick up undocumented immigrants who have just crossed the border.

These incidents are increasing as are the high-speed chases and deadly crashes.

The front-seat passenger in the car that crashed into Lehman died, 67-year-old Donald Childers of Tucson.

The driver, 25-year-old Elanah Tucker, was transported to Banner-University Medical Center in Tucson, with a broken femur. She was later charged with seven felonies, including first-degree murder and second-degree murder. A warrant is out for her arrest.

The two migrants in the back of the vehicle Tucker was driving were taken to Benson Hospital with minor injuries. As well, the Sierra Vista Herald reported that the hawk died.

Lehman, who is 61, was taken to a local hospital with extensive injuries, including a broken femur, tibia and ankle.

As deadly crashes like this one have increased over the last several years, so have questions about whether Custom and Border Protection’s pursuit policy is turning dangerous situations into deadly ones.

The crash in Benson caused one of at least 17 deaths so far this year, nationwide, in crashes where Border Patrol had been in pursuit, according to statements from Customs and Border Protection. Three of those crashes were in Arizona and resulted in four deaths.

In 2021, there were at least 25 deaths in such crashes, seven of which were in Arizona, according to data from the ACLU of Texas and complaints filed with the Department of Homeland Security.

In 2020, there were 14 deaths nationwide, with four in Arizona, according to the ACLU data. The majority of years in the previous decade each had one or two such deaths.

Fleeing law enforcement, 25-year-old Elanah Tucker was severely injured when she crashed, driving excessive speeds in a 35-miles-an-hour zone. Her passenger 67-year-old Donald Childers was killed. Two undocumented immigrants in the back seat suffered minor injuries.

New policy promised but few details

The Department of Homeland Security opened complaints earlier this year, alleging violations of civil rights or civil liberties resulting from incidents related to vehicle pursuits by Customs and Border Protection employees, according to a Feb. 24 memo to Commissioner Chris Magnus. The department’s Office for Civil Rights and Civil Liberties said it is pursuing an investigation.

The complaints, which include incidents from September 2021 to February 2022, alleged that CBP personnel unnecessarily engaged in vehicle pursuits at high rates of speeds that were unwarranted given the alleged crime and that they deployed vehicle immobilization devices or used pursuit techniques that potentially led to serious injury or death, the memo says.

In May, Magnus said the agency was working on a new policy for vehicle pursuits with the intent to increase safety following a slew of deadly crashes and that the policy was expected “soon,” according to The Associated Press.

The current policy mostly leaves the question of whether to pursue a vehicle that is fleeing up to the discretion of agents and officers. It says they can conduct a vehicle pursuit for as long as they can determine that the “law enforcement benefit and need for emergency driving outweighs the immediate and potential danger created by such emergency driving.”

As well, the agency’s use-of-force policy, which outlines rules around using vehicle immobilization devices and offensive driving techniques, says use must be both “objectively reasonable and necessary,” and they should be used in cases where the need to stop the vehicle outweighs the risk created by the use of the driving technique itself.

In Lehman’s crash, the Border Patrol had used a vehicle immobilization device, which spiked the fleeing vehicle’s front left tire.

With the tire losing air, the Expedition continued at high speeds, estimated at 100 miles an hour. About 3 miles later and entering a 35-mile-an-hour zone, the tire came off, and the vehicle began to veer left out of the westbound lane. It went through the intersection and collided with Lehman’s vehicle, which was sitting still in the eastbound left turn lane, according the crash report from the Arizona Department of Public Safety.

Lehman’s car was jolted and came to rest more than 85 feet from where it was hit. The Expedition’s missing tire was later found about 2,300 feet away from the collision site.

Failure to yield tied to migrant numbers

The increase in smuggling incidents and high-speed pursuits is related to an increased number of migrant apprehensions, says U.S. Border Patrol Chief Raul Ortiz.

“Percentage wise, it’s an increase, but it’s not any higher based upon the number of apprehensions we’ve made,” he told the Star in an interview on Sept. 23. “Because our activity has increased, naturally, we’re going to see more failure-to-yields in pursuit, but it isn’t off the charts.”

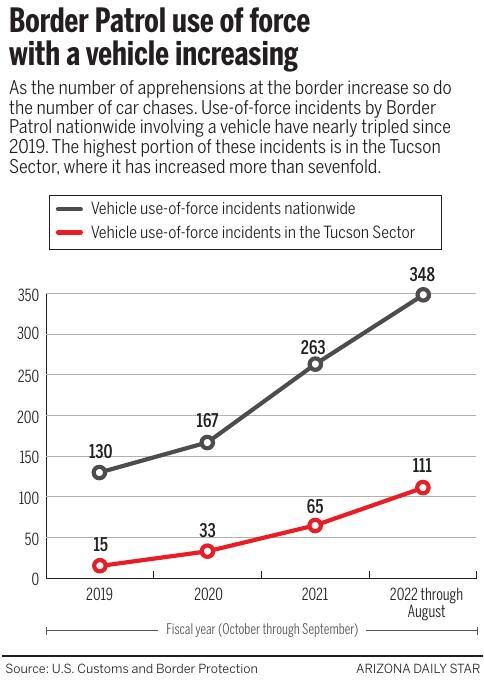

Use-of-force incidents by the Border Patrol nationwide involving a vehicle have nearly tripled since 2019, with nearly 350 incidents nationwide this fiscal year, according to CBP data that is one month shy of a complete year.

The highest portion of these incidents is in the Border Patrol’s Tucson Sector, where it has increased by more than sevenfold to 111 incidents as of the end of August. The data does not include how many of those incidents resulted in a high-speed chase or a death.

Nationwide, the percentage increase from last year in migrant apprehensions has nearly kept pace with the increase in the Border Patrol’s use-of-force incidents involving a vehicle. But in the Tucson Sector, while apprehensions have increased 20% over last year, vehicle use-of-force incidents have increased by 71%.

Lawmakers ask for quick policy action

Ortiz says the agency has made a few adjustments to the pursuit policy already and that it continues to review existing policies across law enforcement organizations to see if there are some best practices it can leverage.

“We are looking at our pursuit policy and ensuring that our agents recognize that there are certain situations where we certainly do not want to pursue, making sure that our agents recognize that if you’re in a school zone or if you’re in a populated area, the risk associated with pursuing a smuggling load in that environment is much more dangerous, not just for them, but also for the public.”

As far as what in the current policy needs to change, he only specifically referred to “pit maneuvers,” which is when a law enforcement vehicle disables a suspect vehicle by striking it on the rear quarter.

“It is very dangerous,” Ortiz said. “We’ve done it a couple of times. And unfortunately, the effects usually resulted in some sort of injury. So we’ve opted to use other means to disable vehicles whenever they are trying to evade apprehension.”

He said the decision to remove pit maneuvers was made before 2021, but one of the complaints filed with Homeland Security referred to an incident in January 2022 where a Border Patrol agent “clipped” a suspect vehicle driving at faster than 70 miles an hour, and it rolled over. The driver, who was allegedly driving nine “non-citizens,” died, the complaint says. One of the other people in the car, a man from Ecuador, died as well.

Lawmakers, including U.S. Reps. Raúl Grijalva and Ann Kirkpatrick, Southern Arizona Democrats, have been asking for expediency in enacting a new policy due to the increased numbers of crashes in these incidents.

The lawmakers cited 21 deaths related to CBP vehicle pursuits so far in 2022, in a September letter to CBP Commissioner Magnus, a former Tucson police chief.

Ortiz didn’t share a timeline on when the policy would be ready.

“We’re working on it right now,” he said in September. “There is an ongoing review. … I know that this is a priority for the commissioner. And we are working closely with the department to make sure that our new pursuit guidance or policy takes the best practices across the country and incorporates that into what we’re experiencing right now.”

‘Sinaloa not in charge of traffic laws’

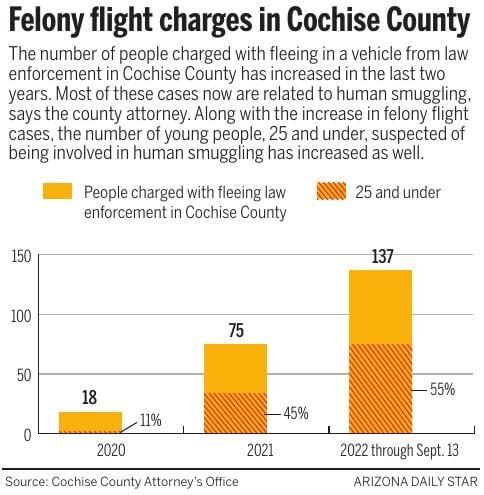

In Cochise County, where Lehman’s crash happened, the number of people charged with the felony of fleeing law enforcement increased in the last three years, from 18 in 2020 to 75 in 2021, to 137 in 2022, as of mid-September, according to data from the Cochise County Attorney’s Office.

If Lehman knew then that high-speed chases like that were becoming a more common occurrence in Cochise County, she says she would not have been down there.

“I wouldn’t be driving anywhere near the freeway down there,” she said.

When asked if law enforcement pursuits can make the situation worse, Cochise County Attorney Brian McIntyre said it’s important to stop suspected smugglers, who are typically working for the Sinaloa cartel.

“Sinaloa is not in charge of traffic laws in this county — that can’t be the deal,” he said. “If we initiate a traffic stop and someone doesn’t pull over, we’re going to make sure that they wind up pulled over in some way. And you don’t know what else is in there, and that’s the other troubling part.”

Suspected smugglers who get apprehended sometimes have weapons and narcotics as well.

In 2019, Cochise County charged 20 people with unlawful flight from law enforcement, and about half were suspected to be related to human smuggling, McIntyre says. In the last two years, about 95% of felony flight cases were related to human smuggling, he says.

The county uses the felony flight charge, often coupled with felony endangerment charges for every person in the vehicles involved, because the state hasn’t had a human smuggling charge, as that is a federal crime.

The Arizona Legislature did pass a law this year that would allow the state and local jurisdictions to charge people with crimes related to human smuggling. McIntyre said in September that it had been enjoined for some time because of default litigation in Maricopa County.

While the number of felony flight charges — not all related to human smuggling — in Pima County is higher than in Cochise County, it has remained relatively constant for at least the last five years, at an average of about 230 felony charges per year and 13 juvenile.

As well, the United States filed 288 felony cases against individuals suspected of smuggling undocumented immigrants in Arizona, including against leaders and coordinators of non-U.S. citizen smuggling organizations, in the three months from April through June. They also charged young drivers, including three juveniles.

These types of cases end up with Cochise County if the federal government declines to charge anyone.

Younger suspects and higher pay

Along with the increase in cases, the number of young people, 25 and under, suspected to be involved in human smuggling has also increased. In 2020, people 25 and under accounted for 11% of felony flight charges in Cochise County. This year, they’ve accounted for 55%, including at least 13 minors.

Cochise County even charged one 14-year-old, but that case transferred to juvenile court.

The amount that criminal organizations pay drivers has increased as well, from $700 to $1,000 per person up to $1,500 to $2,000, McIntyre says.

“The way they flash cash on social media … they’re bringing these groups of people down here — the kids, who absolutely don’t know any better and don’t know how to drive in the first place,” he said.

Criminal organizations are finding young people on social media in cities like Tucson and Phoenix to pick up migrants near the border, and they usually don’t pull over for law enforcement, McIntyre says.

“When we talk about the methods that they’re using to recruit these drivers, they’re actually telling them that as long as you go over 100 miles an hour, they’ll discontinue the pursuit,” he says. “The recruiters’ only interest is getting the migrants to Tucson, Phoenix and Casa Grande as quickly as possible, or else the migrant will get ‘42ed’ back and need a ride again the next day.”

McIntyre is referring to Title 42, a public health policy in the pandemic that allows the government to immediately expel migrants from the country. This has led to a higher percentage of people crossing multiple times. For example, in August, 22% of apprehensions were of individuals who had been apprehended at least once in the last year.

Title 42 may contribute to increase

One reason for the higher number of smuggling cases could be because people are crossing multiple times after being expelled without being entered into the immigration system or given a chance to make an asylum claim, says Daniel Martínez, a University of Arizona School of Sociology associate professor and co-director of the Binational Migration Institute, specializing in the association between increased border enforcement and migration-related outcomes.

As well, border enforcement strategies have pushed people to cross the border in more remote areas, which means they have to drive farther, Martínez said.

“So effectively, you can make the argument that because of where they’re crossing and where they’re being picked up, you’re having people who are spending more and more time in motor vehicles,” he said. “Couple that with the fact that you just see the sheer increase in the volume of people who are crossing, both asylum seekers and undocumented immigrants.”

One solution could be removing Title 42 and improving access to the asylum system, he says.

McIntyre also says the solution has to do with the immigration system, including the asylum system, but says to do this the border has to stop being a “political football.”

“The solution is some kind of actual zero-politics solution,” he said. “How are we going to handle people with legitimate asylum claims? How are we going to have an actual asylum system? What are we going to do about temporary workers? What are we gonna do about all these things? That takes a massive effort of people actually putting aside who spends money on their campaigns and what particular party they belong to and coming up with a solution.”

“Us folks down here, whether we’re Democrats, Republicans, independents or none of the above … we just want to be able to drive to and from work and send our kids to school and not have to worry about somebody doing 110 into our tailgate.”

She survived

Since the crash, Lehman is in constant physical pain and deals with anxiety and emotional distress.

After she went from the hospital to in-patient rehab for about two weeks and then a skilled nursing facility for another two weeks, she and her family fought to get her home, she says.

She’s using a wheelchair but hopes she’ll regain much of her mobility in time. Mostly, she hopes she won’t always be in pain.

“I was able to get down on the floor before and pick something up or sit on the floor, play with the dog,” she said. “I don’t feel like I’m gonna be able to do that again, with the plates in my ankle and the way my knee is. Actually both knees are kinda messed up.”

She just started physical therapy, which she was both looking forward to and dreading because of how painful it would be.

Despite how physically and emotionally challenging her recovery has been so far, Lehman tries to focus on what brings her joy.

She hasn’t been able to get into her backyard because there’s a step she can’t navigate with her wheelchair. But she sits at the window to watch the birds.

“I’m looking forward to being able to just get up and see that a certain hummingbird is outside and just be able to go outside and watch it again or take a picture right there.”

Julia Lehman was involved in a deadly collision with another vehicle that was running from law enforcement in a suspected human smuggling case on July 28. Before the accident she regularly spent time in nature and volunteered with a wildlife rescue organization. She sustained serious injuries that have greatly limited her mobility but hopes that in time she'll be able to get back to doing activities she loves.

Wildlife and nature is her solace, she says. She hopes to be creative again, create artwork and enjoy nature.

“It shouldn’t have happened,” she said. “I was at the wrong place at the wrong time. Just a few seconds earlier that may have delayed me being in that spot before I was hit and could have changed everything. This has touched everything deeply in my life. It’s just unreal to think about that. I have to keep telling myself — I survived.”