Now that the George Alan Kelly story has gone national, picked up by the Associated Press, people think they already know what it means.

They pick the version they want to be true, the one that fits their preconceptions of how the border really is.

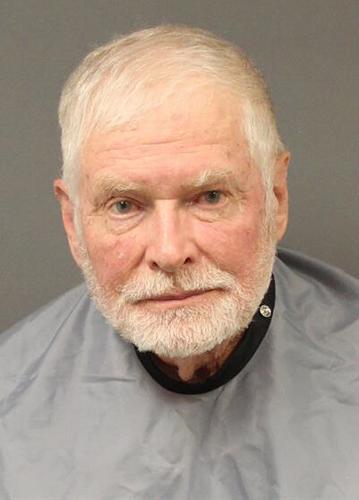

Kelly, 73, is accused of shooting to death a Mexican man just north of the border, in the rural Kino Springs area east of Nogales. Kelly and his wife live there, and he described himself as a rancher, the Nogales International reported.

If you’re the type who watches Fox News, this is the story you will probably choose: An American rancher under siege due to Pres. Biden’s bad border policy, now is accused of murder for simply defending his home against smugglers.

If you’re the type who watches MSNBC, you’re more likely to see it as the story of a vigilante border rancher looking for trouble and killing an innocent migrant.

At a preliminary hearing, now scheduled for Feb. 22, prosecutors and investigators will present their evidence that the killing of 48-year-old Gabriel Cuen-Buitimea, a Mexican citizen from Nogales, Sonora, was a crime. Cuen-Buitimea has previously been convicted of illegal entry at least twice.

But nothing presented at that hearing is likely to change the story people want to tell themselves about the incident leading to Kelly’s arrest.

What’s surprising about this incident, different from others involving ranchers over the years, is that Kelly apparently had his own story of border violence to tell long before this shooting occurred.

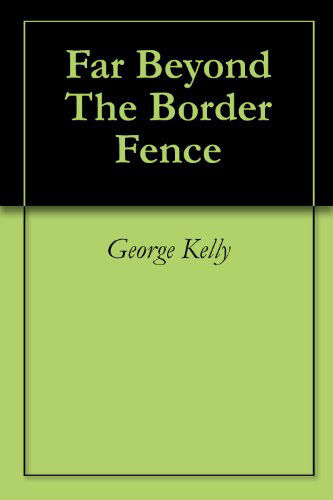

As reported by Angela Gervasi of the Nogales International, there is an unknown little novel, published in 2013 by a “George Alan Kelly” who by all appearances is the same man accused in this case. The story takes place on the “VMR Ranch”; in real life, Kelly and his wife Wanda own a property named the Vermillion Mountain Ranch.

The book is about a rancher named George and his wife Wanda who live near the international line and become embroiled in a violent cross-border incident.

I bought the short book for $2.99 on Amazon yesterday and sped through its 57 pages on my computer. It’s not surprising that “Far Beyond the Border Fence” is not a good book.

But that’s not really the point. What interested me is the kind of story this man living right near the border on a rural property chose to tell about the border.

George and Wanda’s ranch was doing fine until after the 2008 election, when work on a nearby border wall stopped, the book recounts. Then, smugglers and migrants become an increasing problem.

One day in fall, George’s prize horse is stolen, and a cut-open fence suggests the horse was taken to Mexico, the story goes on. The effort to recover the horse, a gift from George’s son in Montana, leads to the kidnapping of one son and that son’s wife. That then leads to various illegal incursions into Mexico on horseback by George, his other son and the local sheriff.

Finally, deep in the Sierra Madre, they uncover something even more sinister — a terrorist plot involving a dirty bomb! The drug traffickers in a nearby Mexican town have become entangled in a plot involving Ecuadorians and Arabs to destroy Santa Cruz, a U.S. border town that seems to stand in for Nogales, as well as its twin city in Mexico.

Near the climax of the story comes this passage: “Then a voice came from the west, it was Eben. In broken English he issued a warning, that if the former hostages didn’t surrender, he would remotely detonate the bomb. The Sheriff hollered for him to go ahead. No reply.

“The Sheriff was sure that Eben’s plan for his own personal Jehad wouldn’t forego the mass destruction of Santa Cruz just to blow up an Arizona Sheriff and ten more gentiles. Eben, realizing that his bluff had been called, screamed out what the Sheriff figured were the Arabic words for son of a bitch or worse.”

You will not be surprised to learn that after much gunfire, the rancher and his sons, bloodied but unbowed, return to the ranch in time for Christmas. Sorry for the spoiler.

Rancher stories have been a staple of border news for decades. Back in the late 1990s, I spent significant time on Cochise County ranches, compiling the depredations suffered there at the hands of border crossers who cut fences and burglarized homes and occasionally committed violence.

There were also the ranchers accused of taking the law into their own hands — the Hanigans in the 1980s, and the Barnetts in the early 2000s.

Over time, these became a staple of conservative news outlets, a cliché, and I soured on them. Border-rancher stories took on the trappings of stereotype, starring the same one or two characters, who I learned they were not even representative of the broader experiences of borderland ranchers — variable, not uniformly of suffering or violence.

If George Alan Kelly did indeed shoot Gabriel Cuen-Buitimea, there is infinite variety in the possible reasons, and ultimately a yes-or-no decision on whether the killing was a crime.

In the meantime we shouldn’t fall back on old tropes in assessing the case, a danger that even border ranchers apparently fall into when they take pen in hand.

Get your morning recap of today's local news and read the full stories here: tucne.ws/morning