For Rep. Juan Ciscomani, the Tucson area’s new congressman, his big opportunity last month contained a lesson.

Ciscomani, a Republican, got to deliver his party’s Spanish-language response to President Joe Biden’s State of the Union speech.

Ciscomani’s speech got relatively wide notice because it was the only formal response given by a GOP congressman this year. And frankly, as some national publications pointed out, it was better than the uninspiring English-language response given by Arkansas Gov. Sarah Huckabee Sanders.

Of course, Ciscomani wouldn’t have had the chance if he didn’t speak Spanish. That seems obvious, but as so many immigrant families have found out, even Spanish speakers living in Tucson, the language can disappear from a family fast, over just a couple of generations.

“It takes effort to maintain your Spanish,” he said in a recent interview conducted in that language.

Rep. Ciscomani sat down with Star columnist Tim Steller following the congressman's speech responding to President Biden's State of the Union address. Video by Tim Steller / Arizona Daily Star.

Ciscomani and I have known each other since 2015, when he took charge of then-Gov. Doug Ducey’s Tucson office and I wrote a column about him. When we speak, it’s mostly in English, but with some Spanish mixed in.

After Ciscomani’s State of the Union response, I asked if he would do an interview on his experience with language and bilingualism. We decided to to it in Spanish.

Now, Ciscomani is not unique among our local elected officials in coming from a Spanish-speaking background.

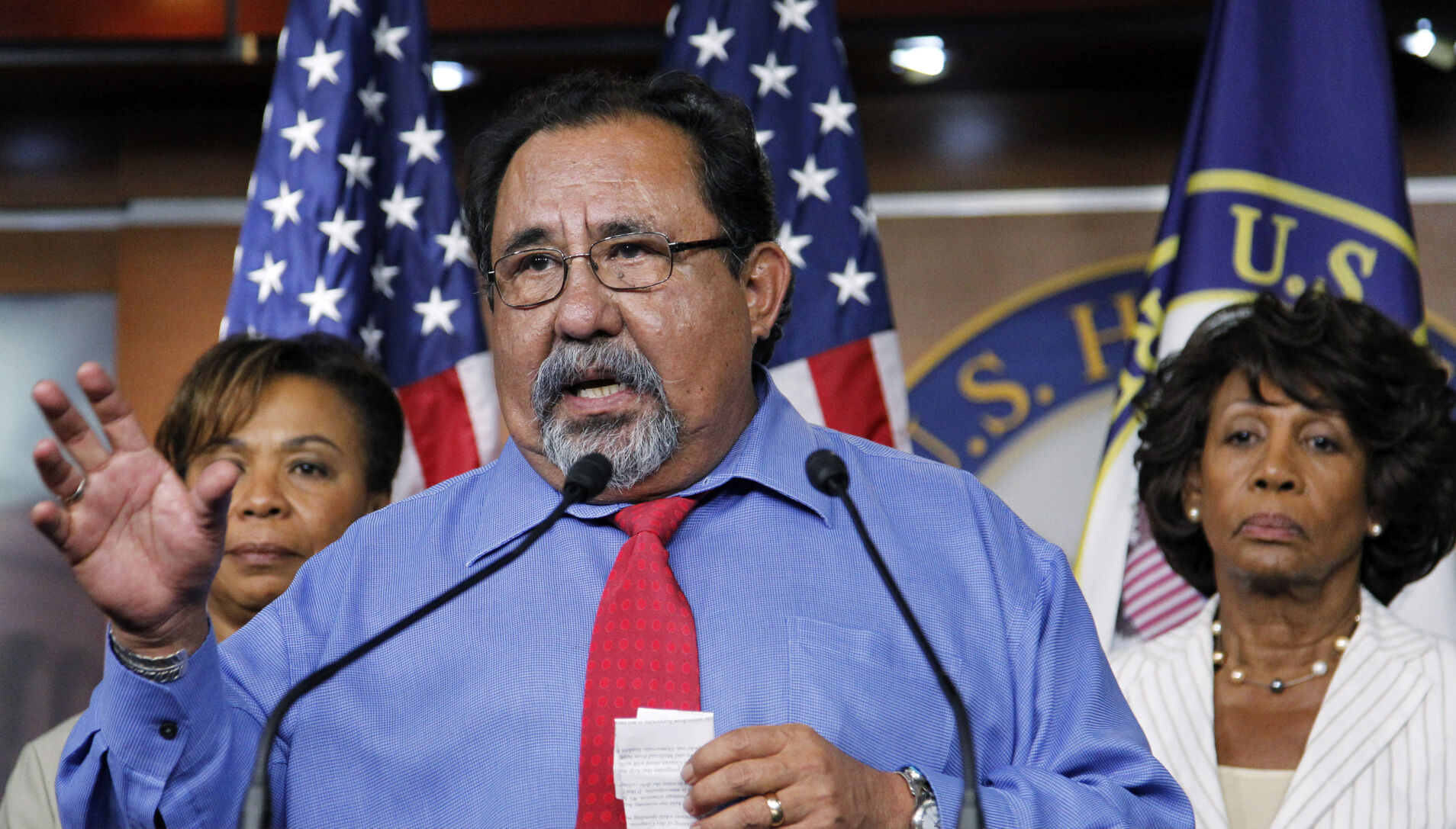

Longtime U.S. Rep. Raúl Grijalva is bilingual and has delivered comments in Spanish on behalf of the Democrats in response to Republican presidents’ State of the Union speeches. Tucson Mayor Regina Romero also grew up speaking Spanish, as have other local office holders over the years. Ciscomani is just the latest, but relatively rare as a Spanish-speaking Republican office-holder in southern Arizona.

Congressional Progressive Caucus co-chair, Rep. Raúl Grijalva, D-Ariz., center, expresses his disapproval of the debt ceiling agreement during a news conference on Capitol Hill in Washington, Aug. 1, 2011.

His family came from Hermosillo, Sonora to Tucson when he was 11. He had learned a little English in classes, but his parents didn’t know any.

“The classes taught us the basics,” he said in Spanish. “But when we got here, it was from going to school, being with friends, from the television.”

His parents gradually learned English, but they didn’t use it at home.

“My parents had an interesting rule: ‘In our house, we’re going to speak Spanish, so we don’t forget it,’ “ he said.

The benefits became tangible, Ciscomani said: In his first job at a Wendy’s, he was paid an extra 15 cents per hour for being bilingual.

Spanish lacks prestige

His parents were smart, though, to be worried about losing the language. I spoke to a University of Arizona sociolinguist, Professor of Spanish and Portuguese Ana Maria Carvalho, who told me that even this close to Mexico, the same immigrant language patterns seen elsewhere in the country often hold true.

“What we find in Arizona in general is what we call a three-generation language shift — meaning that the migrants, what we call Generation One in the U.S., they come with Spanish. Their children are usually bilingual, in Spanish and English. They learn Spanish at home and English everywhere else. But those kids, their children, are usually monolingual in English.”

Even in Tucson, it may only take a couple of generations for Spanish to disappear in a family. It’s sad — grandparents often have trouble speaking with grandchildren.

Why does it happen? Well, English is not only the official language of government and schooling, but it remains, Carvalho said, the language of “prestige” in the region after all these years.

“There’s a lot of pressure to speak English only,” she said. “Spanish does not have a lot of social prestige. English is the dominant prestigious language in Arizona.”

Spanish is not suppressed now the way it was in earlier generations, when schoolchildren were sometimes punished harshly for speaking it, but the vestiges of that era linger.

Children turn to English

Ciscomani, 40, told me he was fortunate not to have suffered the abuse of some earlier Spanish-speaking generations. But he and his family have lived the typical immigrant pattern when it comes to language.

“When you grow up in a bilingual home, you become the translator at the bank, with doctors, with the electric company — with whatever service your parents need,” he said. “You grow up a little faster in that sense.”

He and his wife Laura both grew up in Spanish-speaking homes and now are trying to raise six kids to be bilingual. They do it the way their parents did, by speaking Spanish in the home and letting the kids learn English outside. But that can be hard.

The kids might say something to him in English, Ciscomani said, and he’ll answer it in English without thinking.

“It isn’t that they don’t want to [speak Spanish], but it takes an effort to do it. Often in everyday life, you don’t focus on that.”

Also, he and Laura can see the language ability diminishing, from the older children to the younger ones.

“The little ones speak English with the littler ones,” he said. “At home they start speaking more and more English among them. They start losing Spanish — the younger they are, the less Spanish they speak.”

Opportunity presents itself

Carvalho told me it’s hard to keep the younger generations interested in the family’s first language.

“Societal pressure to use English is big,” she said. “English is seen as the language of success and social mobility.”

It helps if the children are in regular contact with family members — say, cousins and aunts and uncles in Sonora — who are monolingual Spanish speakers. It also helps if they live in neighborhoods where Spanish is regularly spoken.

At home, she said, parents can also try to increase the perceived prestige of the language by having books in Spanish, watching movies in Spanish, looking at art created by Spanish speakers.

Ciscomani has, perhaps, stumbled into another way of increasing the prestige of the language.

“When I gave the response to the president’s speech, I told the kids, ‘This is why it’s important to speak Spanish, because opportunities like this open up. If I didn’t speak Spanish, or if I spoke it badly, this opportunity wouldn’t have presented itself.’ “