On May 28, 2022, Pima County Attorney Laura Conover composed a news release announcing the exoneration of Louis Taylor, who was convicted for setting the 1970 Pioneer Hotel fire.

She sounded convinced of the righteousness of the decision, but she never published the release.

Then on Aug. 3, she wrote another news release announcing she would not exonerate Taylor, sounding equally convinced of the opposite decision.

The explanation for why she changed her mind has been the subject of curiosity and speculation since then. Conover has said she was simply preparing for different possible outcomes.

It’s not just idle wonder: Exonerating Taylor would have meant he is no longer legally responsible for 28 deaths and would have opened up Pima County to liability for the 42 years he spent in prison.

Now Tucsonans have an explanation, probably partial but also plausible, for the reversal. And it came from a surprising source: Nina Trasoff, the former TV news anchor and Tucson City Council member.

Trasoff wrote two affidavits for two separate cases involving Louis Taylor in recent weeks, both about her work on the May, 2022 news release announcing the exoneration.

The key one, written March 9, says this: Conover “told me she had not gone forward with the original press release, which had been scheduled for May 28, because Phoenix lawyers had threatened bar discipline and possible disbarment if she went forward with the plan to exonerate Mr. Taylor.”

Trasoff’s affidavit was explosive because it suggested that Conover walked up to the edge of exonerating Taylor before deciding not to because it threatened her own career.

Conover has neither confirmed nor denied that she said this. She initially accepted an interview request for Friday, then said she could not go ahead because of the pending litigation between Taylor and Pima County and the likelihood that she will be deposed in coming weeks or months.

Her statement earlier this week, after Trasoff’s affidavit was filed in Pima County Superior Court, was this:

“High-level prosecutorial decisions made by county attorneys and district attorneys across the nation often draw strong and sometimes fierce opinions. In performing my duties as prosecutor, I’ve proven my willingness and availability to listen to diverse feedback. However, I’ve also proven that I make decisions based on facts and the law. While I carefully consider the opinions of my senior leadership team and the opinions of interested members of the community, the ultimate decisions I make are my own.”

Again, she didn’t deny saying that to Trasoff. She said being county attorney is a tough and complicated job — which it sure is, especially when you flip-flop on a crucial, sensitive decision like exonerating Taylor.

Exoneration needed to seek damages

Conover, now in her third year as the county’s top prosecutor, campaigned in part on bringing justice for Taylor, convicted as a teen in 1972 for setting the Pioneer Hotel fire and killing 28 people.

His conviction has long been a cause célèbre around Arizona — considered dubious because of an investigator’s racism, questionable investigative techniques and doubts that the fire was caused by arson at all.

Though Taylor was released from prison in 2013 after pleading no contest to the charges, he was never exonerated. He filed a federal civil suit against the county in 2015 that is continuing, but the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals said he could not collect damages for his imprisonment as long as his no-contest plea stood.

In other words, he would have to be exonerated.

Before Conover took office in January 2021, representatives of outgoing county attorney Barbara LaWall’s office contended that legal ethics prohibited her from getting involved in Taylor’s civil suit against the county.

Normally, a county attorney and her deputies would be expected to defend the county, but Conover had said during the campaign that she worked briefly on Taylor’s case when she was a law student and she also said during the campaign the county attorney’s office had fumbled Taylor’s exoneration. LaWall’s team found that she had a conflict of interest, and they passed the civil case off to outside attorneys.

Conover assigned former aide Gabriel “Jack” Chin to review Taylor’s conviction and make a recommendation about exoneration anyway.

Family, lawyers told of planned exoneration

Over Memorial Day weekend, 2022, Conover and her team had reached a conclusion and were preparing to announce the exoneration.

This would be a momentous decision not just because Taylor would no longer be considered culpable for the deadly fire, but also because of the likelihood it would mean a bigger payout by the county in Taylor’s lawsuit.

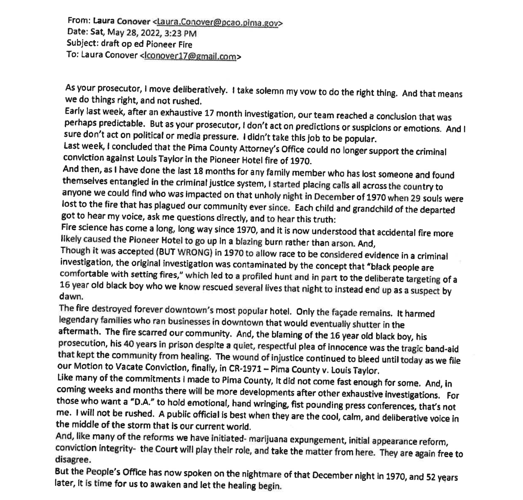

On Saturday, May 28, Conover had put together a news release, with Trasoff’s help, that read like this: “Last week, I concluded that the Pima County Attorney’s office could no longer support the criminal conviction against Louis Taylor in the pioneer Hotel fire of 1970.”

“And then, as I have done the last 18 months for any family member who has lost someone and found themselves entangled in the criminal justice system, I started placing calls all across the country to anyone we could find who was impacted on that unholy night in December of 1970 when 29 souls were lost to the fire that has plagued our community ever since.”

Indeed, Conover went so far as to alert Taylor’s lawyers and some victims’ family members that she planned to exonerate Taylor. Then suddenly over that weekend, plans changed. She decided not to proceed with exoneration the next week.

On Aug. 3, the day after an executive session with the Pima County Board of Supervisors discussing the Taylor case, she announced she was not going to exonerate Taylor after all.

Speculation likely to continue

When news of Trasoff’s latest affidavit broke, suspicion naturally drifted toward Nick Acedo. He is the Chandler-based attorney who took over defending Pima County in the Louis Taylor civil case at the end of LaWall’s tenure.

Could he be a “Phoenix lawyer” who threatened Conover with a Bar complaint?

“Neither Pima County nor its attorneys have ever threatened Ms. Conover,” Acedo told me Thursday.

He specified, when I asked, that he had not threatened to report Conover to the State Bar.

Did something happen in the Aug. 2 supervisors meeting when they discussed the Taylor case in executive session? We don’t know — state law forbids them from publicly discussing what happened in executive session.

All we know is that on May 28, Conover sounded convinced that an exoneration of Taylor was justified. But on Aug 3. she was convinced of the opposite: The “review of the Taylor criminal case is complete and did not find any new evidence of innocence. Therefore, no further action will be taken in the Taylor criminal case.”

It was odd, to say the least — and upsetting to Conover’s former political allies representing Taylor. They sought an explanation and found Trasoff’s account, one that is not edifying if you believe that a prosecutor should stand for justice, come what may.

But undoubtedly this is not final word, just the beginning of an understanding of why Taylor remains responsible, instead of exonerated, for the Pioneer Hotel fire.

Photos of the 1970 Pioneer Hotel fire in downtown Tucson

The Pioneer Hotel never recovered from the 1970 fire, said Bettina Lyons, niece of the couple who owned the hotel. "Even though they put money into it and put sprinkler systems in, people did not come to stay."

Victims are removed from the front entrance to the Pioneer Hotel in Dec. 1970.

A injured firefighter is wheeled to an ambulance at the Pioneer Hotel fire on Dec. 20, 1970.

In the end, the Pioneer Hotel fire killed 29 people, some of them jumping from windows to escape the flames. Louis Taylor was convicted of arson. The first articles ran in the Star Dec. 20, 1970.

The Pioneer Hotel in 1961.

Firefighters on an old Tucson Fire ladder truck help a woman down from the upper floors during the Pioneer Hotel fire on Dec. 20, 1970.

A firefighter sprays water on windows of the upper floors of the Pioneer Hotel fire on Dec. 20, 1970.

A man stands at the window on one of the upper floors of the Pioneer Hotel fire on Dec. 20, 1970, as the fire rages above.

A firefighter helps an unidentified man after plucking him from a room near the top of the Pioneer International Hotel which caught fire early in Dec. 1970.

Tucson firefighers apply a steady stream of water during the Pioneer Hotel fire in Dec. 1970. Tucson's firefighting equipment was ruled inadequate following this fire when they were unable to aid many trapped on the higher floors.

Flames and smoke shoot from the windows in the upper floors during the Pioneer Hotel fire in Dec. 1970.

Flames and smoke shoot from the windows in the upper floors as firefighters extend the ladder to save those below during the Pioneer Hotel fire in Dec. 1970.

Victims are removed from the front entrance to the Pioneer Hotel in Dec. 1970.

Victims are removed from the front the entrance to the Pioneer Hotel in Dec. 1970.

Smoke billows from the upper floor of the Pioneer International Hotel as three firemen work to rescue survivors of the early-morning blaze. The firemen at the bottom is helping an elderly Pioneer tenant to walk down the ladder.

Fireman help the injured at the Pioneer Hotel blaze in Dec. 1970.

A hotel patron is helped down the ladder to safety during the Pioneer Hotel Fire in Dec. 1970.

Pioneer Hotel Fire

Tucson firefighters climb a ladder at the Pioneer Hotel Fire in 1970. Courtesy of Tucson Fire Department

Tucson firefighters help an elderly patron down the ladder at the Pioneer Hotel fire in Tucson on Dec. 20, 1970.

G.L. Scoggins, catering manager, talks to exhausted Tucson firefighers at the Pioneer Hotel fire in Tucson on Dec. 20, 1970.

An exhausted Tucson firefighter at the Pioneer Hotel fire in Tucson on Dec. 20, 1970.

People draped in blankets outside the Pioneer Hotel in Tucson after a fatal fire on Dec. 20, 1970.

People in downtown Tucson gaze up at the Pioneer Hotel the morning after the deadly fire in Dec. 1970.

People in downtown Tucson gaze up at the Pioneer Hotel the morning after the deadly fire in Dec. 1970.

Aftermath of the Pioneer Hotel Fire in Dec. 1970.

The aftermath of the Pioneer Hotel Fire in Dec. 1970.

The bedroom suite at the Pioneer Hotel kept by the Steinfelds, owners of Steinfelds Department Store. The couple died in the massive hotel fire on Dec. 20, 1970.

Aftermath of the Pioneer Hotel in Dec. 1970.

Funeral of victims of the Pioneer Hotel Fire in Dec. 1970.

Louis Taylor in 1970. Taylor was tried and convicted of 28 counts of felony murder in connection with the fire at the Pioneer Hotel, Tucson.

Arizona prison inmate Louis C. Taylor, serving a life sentence after being convicted in the deaths of 28 people in the 1970 Pioneer Hotel fire. A 29th person died later of injuries from the fire.

Louis Taylor shakes the hand of his first attorney from 1972, Howard Kashman, back to camera, as his current defense team from Phoenix surrounds him after a hearing in Pima County Superior Court in Tucson, Ariz. on Tuesday April 2, 2013. Taylor, who was originally convicted of 28 counts of felony murder in connection with the fire, was released from prison after 42 years.

Get your morning recap of today's local news and read the full stories here: tucne.ws/morning