Just two weeks after my dad died, it’s becoming hard to believe he inhabited this era.

He lived in it, yes, but he defied its spirit.

Bob Steller was computer literate, but he didn’t go down conspiracy-theory rabbit holes, as many older Americans have done in recent years.

Raised in a Republican household, he was a committed Democrat, but he didn’t get into big battles over politics.

He lived in the middle of Minneapolis for six decades, and was a snowbird in Tucson for two, but he didn’t fear the people who passed by or rang his doorbell. He didn’t have a gun to meet them with.

He was good to people, warm and compassionate, and his faith in others paid off over 87 years. What a foreign concept in this fearful and hostile time.

It was a shock when my brother Chris called me Wednesday afternoon, April 26, and told me our dad had fallen, that he was at the hospital and that it wasn’t clear what had happened or what the prospects were.

The next day I headed north, and for another day, we lived under the illusion that things could be OK. Despite our dad being in his upper 80s, he was mentally and physically vibrant.

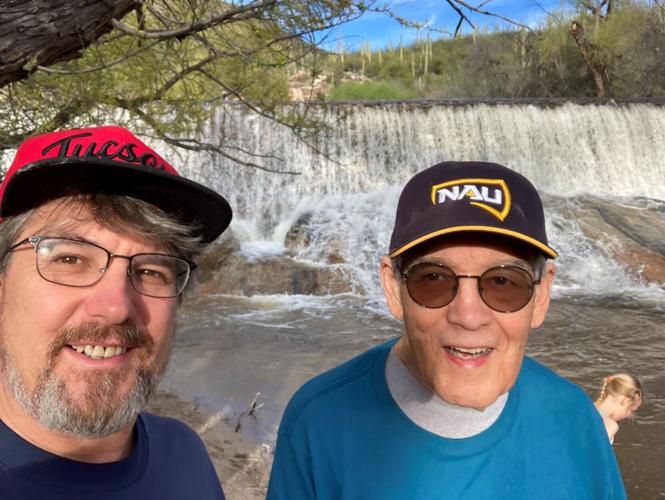

When he was in Tucson for three weeks in March, we went to the book festival, hiked in various desert spots, took other walks around town, read and chatted on my porch, and planned for the future.

The last day he was here, he said he’d like to see the wildflowers at Picacho Peak, so we went there in the morning before his plane left in the afternoon. We went up and down various rocky paths, using walking sticks.

As we headed up one trail, a middle-aged woman and her older mother passed us, walking gingerly back toward the trailhead. After my dad and I went as far as we wanted to, we returned and came up behind that same pair near the beginning of the trail. The younger woman stepped aside, asked us to pass them by and explained, “My mom is 87.”

As my dad trudged quickly past, he looked back and unselfconsciously said, “So am I!” I cringed and smiled simultaneously. He was just being friendly.

Our mom, Judy Steller, died in December after years of decline with Alzheimer’s disease. Our dad took care of her during most of those years, to the point of exhaustion, and we were excited for him to have more time to explore his many interests.

That’s what he was doing when he fell. He drove to the Minneapolis Institute of Art for a class there, parked on the street and was walking down the sidewalk outside the museum when he collapsed.

On Friday, April 28, it became clear he wasn’t going to get more time to explore. He had suffered a cardiac arrest, and the doctors told us the brain damage from lack of oxygen was serious.

He was on a ventilator at the time, and the decision to take him off wasn’t difficult. He had also suffered a broken vertebrae in his neck and a bruised spine — he likely was paralyzed as well as brain damaged. In a medical directive, he had specified that if he suffered significant brain damage, he wanted “care for comfort,” not to be kept alive by machines.

It wasn’t really our choice to make — he had made it for us.

Relieving that burden was typical of Bob. He grew up in Bowling Green, Ohio, in the '40s and '50s, living through World War II and all the American social upheavals in subsequent decades. He still emerged hopeful and kind, carrying that spirit all the way into the cynical and sinister 2020s.

His faith in others remained, sustaining his own enthusiasm, even as many Americans let their trust whither into cynicism.

This isn’t to say he had no toughness. He played center on football teams through high school and four years of college. Those were the days before facemasks — imagine being a lineman with no facemask— and he broke his nose several times, injuries that you could see if you looked at his face closely.

He had an assured presence. On two different occasions as a young man he disarmed people who had worrisome intentions by saying something to the effect of “Give me the gun.” Both times they gave it to him.

Unlike many male media personalities today, and the many youth who unfortunately follow them, Bob Steller did not care about displaying his masculinity. He did what he enjoyed.

When I was a kid, Bob took me camping and fishing but also to plays and concerts. Up till the end, he sang in a church choir, and he always adored gardening. He also liked watching football and, if I was around, soccer. He taught me to cook when I was home after school — we’d make spaghetti sauce, chili or meatloaf as MASH reruns played on TV.

He spent a career teaching English composition and literature at a community college in suburban St. Paul. When I went into his apartment, the book at the top of his stack, next to his neatly made bed, was Boxelder Bug Variations by the Minnesota poet Bill Holm (who, coincidentally, spent much time in his later years in Patagonia, Arizona).

Bob Steller didn’t have to work hard to be enthusiastic, warm and accepting. Most of the time, it’s just the way he was.

I got some of that from him, but I also got my mom’s feistiness and my own special blend of ego and temper. It takes effort for me, sometimes, to channel that Bob Steller energy, to drop the judgment and self-interest and instead practice acceptance and enjoyment of others and what they bring.

That spirit contrasts so much with the angry American time we’re in. For our dad, a gentle, enthusiastic spirit came naturally. For most of us, in this hostile and fearful time, it’s something to pursue and cultivate.