The Santa Rita Experimental Range has already been studied for a longer time and across a larger area than just about any other place in North America, but now researchers are taking things to a whole new level.

A team from the National Ecological Observatory Network, or NEON, recently completed five days of flights over the University of Arizona-run rangeland research facility south of Tucson in an aircraft packed with science instruments.

Operating out of the Million Air hangar at Tucson International Airport, the state-of-the-art survey by NEON’s Airborne Observation Platform took high-resolution measurements and imagery to document what’s growing across the entire 52,000-acre experimental range.

The NEON Airborne Observation Platform airplane parked in the Million Air hangar at Tucson International Airport on Sept. 15, in between science flights over the Santa Rita Experimental Range.

The flights are part of a sweeping, nationwide effort by NEON to collect and share decades worth of data that can be used to study changes across the full range of habitat types found in the U.S. — from deserts to tropical forests, tiny streams to the Great Lakes.

The Santa Rita Experimental Range — and the Santa Rita Mountains, south of Tucson — as seen from the air in 2018 during data collection flights by the National Science Foundation’s NEON Airborne Observation Platform.

The ambitious project, launched in 2011 by the National Science Foundation and operated by nonprofit applied research contractor Battelle, includes 81 field sites from Alaska to Puerto Rico. A wide range of information is gathered at each site in a standardized way so researchers can make meaningful comparisons across the network.

“It’s a long-term, 30-year project looking at ecological change over time,” said Abraham Karam, NEON’s field operations manager in Tucson. “The spatial coverage and the temporal coverage is what sets us apart from other projects.”

Mitch McClaran, the U of A’s director for research at the Santa Rita Experimental Range, framed NEON in loftier terms: “They’re trying to do ecology on a continental scale.”

Of course, the 123-year-old Santa Rita range has a fairly monumental mission of its own: “We see time,” McClaran said.

The first fence

The 80-square-mile outdoor ecology lab slopes down the western flank of the Santa Ritas from about 5,000 feet to about 2,500 feet — or, as McClaran put it, from “foothills and skirt to grassland and desert shrub.”

If you’ve ever driven to Madera Canyon, you’ve crossed through a portion of the range.

“It’s got a lot of elevation range, a lot of precipitation and climate (range) and 30 different soil types,” McClaran said. “It’s very attractive to researchers for that range of settings.”

The headquarters are housed in a cluster of historic buildings on U.S. Forest Service land in Florida Canyon, at the southern edge of the range. Hudbay Mineral’s proposed Copper World mining project sits just off the northeastern corner of the range.

The range was established in 1902, 10 years before Arizona statehood, as the first rangeland experiment station in the U.S. “and probably the world,” McClaran said.

Mitch McClaran, professor of range management for the University of Arizona, looks over a repeat photography site while taking updated photos in 2007 at the Santa Rita Experimental Range south of Tucson. The repeat photography collection for the experimental range dates back to 1902.

U of A professor and agricultural researcher Robert Forbes, namesake of the Forbes Building just south of Old Main, is widely credited with the idea.

Forbes wanted to find a scientific answer to a series of punishing droughts in the late 19th century that diminished vegetation and decimated livestock herds across the Southwest, so he convinced the federal government to fence off a large swath of open range, 35 miles from Tucson, where researchers could figure out just how much grazing the land could sustain.

“It was the first fence around public-domain rangeland,” said McClaran, now in his 40th year as a professor of range management with U of A’s School of Natural Resources and the Environment. “And so for the next 12 years, it was ungrazed.”

Then the cattle were let back in to gauge the land’s “carrying capacity” and test out different range-management techniques — everywhere, that is, except on about 15 control plots of desert that were kept sealed off behind exclosure fencing and haven’t seen any grazing since, McClaran said.

“The history (of the range) has always included something to do with livestock,” he said, “but over that 123 years, the research attention has expanded greatly to anything related to natural resources and human use.”

Range life

The land was administered by the Forest Service until 1987, when the state took ownership of it as part of the exchange that led to the creation of Buenos Aires National Wildlife Refuge. Since then, the U of A has managed the Santa Rita range and its exhaustive archive of research reports spanning more than a century.

“Because of the long-term record, we know how and where things have changed, and we have a pretty good idea why,” McClaran said. “We have land-use records. We know where there was fire. We know what amount of grazing was taking place across the Santa Rita since 1916, every pasture.”

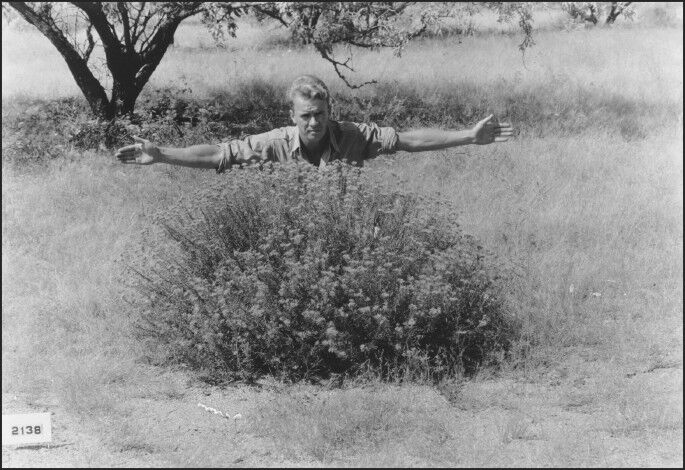

Robert Humphrey shows off a large burroweed plant on the Santa Rita Experimental Range near Tucson in 1934.

All those old documents used to be kept in one of the buildings in Florida Canyon, he said, but they were moved to the U of A campus for safekeeping after a string of arson fires on the range in 1994.

The following year, the university began digitizing the contents of those filing cabinets so the range’s historic data could be made available to everyone online. McClaran said it took about three years of scanning to get what he called “the primary stuff” uploaded to the internet.

The range now plays host to between 30 and 40 separate research projects each year, and hundreds of peer-reviewed studies have been published using data collected there. What’s being learned can be directly applied to more than 40 million acres of semi-arid rangeland with similar characteristics in the U.S. and northern Mexico, McClaran said.

Grazing also goes on throughout the year on select parts of the Santa Rita.

At the moment, McClaran said, there are about 400 cattle out there divided into two main herds. The livestock is provided by a private cow-calf operation that pays the university the standard state-land grazing fee, minus a small discount for allowing some experimentation with the animals.

For example, the range is presently hosting the largest experiment ever conducted on public land using so-called virtual fencing — basically GPS collars that use sounds and mild electric shocks to move cattle and keep them to their assigned areas.

“Now we’re in the 21st century, and the technology is not barbed wire but satellite-based control of the location of animals, and so we’re testing that as well,” McClaran said.

NEON established a terrestrial field site at the Santa Rita range about a decade ago to represent the Desert Southwest in its national network of ecosystem domains.

Their setup includes a 26-foot-tall flux tower bristling with sensory equipment and roughly 60 scattered scientific plots, where they measure in their standardized way everything from mosquitos, small mammals and other wildlife to soil composition and seasonal changes in plants.

“And all that data gets put up on their website,” McClaran said.

Going airborne

During NEON’s flights last month, the visiting four-person crew from Colorado scanned the range with an imaging spectrometer, a laser mapping tool called a lidar and a high-resolution camera to record reference photos at a higher resolution than what you’ll find on Google Earth.

The instruments are mounted inside a de Havilland Canada DHC-6 Twin Otter, a two-prop workhorse of an airplane that flies slow and steady, carries a lot of weight and can operate in almost any climate.

The crew would fly for up to four hours at a time, crisscrossing the range at about 115 mph and 3,000 feet off the ground in long, north-south lines — roughly 90 of them in all, each separated by about a quarter of a mile.

Haynes

“You can kind of think of it as sort of like mowing the lawn,” said NEON airborne sensor operator Mitch Haynes. “We fly north, do a little U-turn, then head south and just keep going back and forth.”

Pilot Vincent Maarschalkerweerd joked that when the pattern gets too monotonous for him, he just takes a nap.

The aerial observations are “ground-truthed” by Karam and his team of field ecologists, who also spend a great deal of time on the range collecting their own trove of data. This year, for example, the local NEON ground team is assessing root biomass by painstakingly extracting core samples from the soil.

“We offer this really solid platform for people to ask experimental questions that I think otherwise would be difficult to answer without something the size of this,” Karam said.

NEON’s flying season typically runs from March through September, with a goal of capturing survey sites around the country when their dominant plant species are at their greenest.

“It’s to measure peak productivity for all the vegetation, so, you know, we’re looking for full canopies,” Karam explained.

Karam

When NEON was originally conceived, the plan was to fly over the entire network of sites every year, but with just two aircraft and the whole country to traverse, Haynes said they have settled into a more modest objective of hitting each location at least three times every five years.

This was the seventh year of aerial data collection over the Santa Rita range since 2017.

This year’s stop in Tucson saw the crew battling late-summer heat that messed with their scientific instruments and monsoon clouds that diminished their spectrometer readings or grounded the airplane altogether.

It ended up taking them 17 days to complete their five flights over the Santa Rita range and two flights over the Jornada Experimental Range, in the Chihuahuan Desert near Las Cruces, New Mexico. Stormy weather kept them from flying the other 10 days they were here.

The lidar laser sticks out from the bottom of the NEON Airborne Observation Platform airplane at the Million Air hangar at Tucson International Airport.

Even so, they managed to compile more than 5 terabytes of raw data from the Santa Rita alone. All of that information will be processed in the coming months so it can be released for free on the NEON website to anyone who might be interested in it.

“I think one of the cool things about the airborne data — and all NEON data — is that it’s not specifically looking at one thing,” Haynes said. “We’re just capturing it all, and people can use it for all sorts of different things.”

Seeing time

The U of A has its own website crammed full of free data from the Santa Rita range, some of it dating back a century or more. There are maps, drone imagery, plant inventories and soil readings, as well as ongoing vegetation transects that started in the 1950s and rainfall measurements that started in the 1920s.

But the oldest and best known set of records is the repeat photography collection, which ranks as one of the largest and most accessible of its kind in the world.

The effort to document changes in vegetation over time began in 1902 with photographs taken at 16 different locations. Since then, the number of repeat photo stations has grown to 128, most of which are still actively monitored today.

The average interval between pictures is 15 to 20 years, though since 2000, McClaran has seen to it that every active site gets photographed at least once every six years or so.

NEON field ecologists Josh Hoogenboom, left, and Morgan Fowler collect soil cores to measure below-ground plant biomass at the Santa Rita Experimental Range in September.

The entire series is available on the website, searchable by location, year or even keywords that might show up in the text for each entry. You can also view all of the images from a given site side-by-side in chronological order, allowing you to follow along as a single mesquite emerges from the middle of a bush in 1935 and grows into a modest tree over the course of 80 years.

“Probably six generations of scientists are represented in that collection,” McClaran said, himself included.

He started taking repeat photographs on the range in the late 1980s. In 1999, he ended up doing the entire set by himself — all 100-plus sites over the course of the year. “Man, I was busy,” he said. “That was a busy time.”

Now McClaran recruits at least one other person to join him for the annual photography field trip, usually over spring break in March, before the mesquites leaf out and block the view of what’s in the background. They typically shoot about 25 of the sites each year on a rotating basis, but it still takes them about five days and a good deal of hiking to catalog even that many locations.

It comes with the territory, McClaran said. Studying ecosystem changes at landscape scale requires perseverance and a decades-long attention span. NEON and the Santa Rita range are proof of that.

“You can’t see the change that’s going to happen in the future, but you can see the change that happened in the past,” McClaran said. “That’s the time that we see. It gives us a better appreciation for what’s changed and a better understanding of how it may change in the future.”