A weird feeling came over me as I walked among demonstrators at El Salvador’s consulate in Tucson Wednesday, the blue and white stripes of the Salvadoran flag fluttering above the crowd on East Fifth Street.

It was the sense that I was hearing some sort of historical echo, bent by the years. The tune was familiar, but in a different key.

Americans were demonstrating at a Salvadoran consulate against that country’s government for its role in supporting our own right-wing government’s human-rights abuses.

Arizona Daily Star columnist Tim Steller

During the 1980s civil war, demonstrators in San Salvador regularly targeted the U.S. Embassy, protesting our government’s role in supporting their right-wing government and its human-rights abuses.

Times change, roles reverse, but the themes remain the same: Safety vs. danger, freedom vs. repression, left vs. right.

Dora Rodriguez, a Tucsonan who fled that country in 1980, can also hear the troubling echoes.

“For me, as a Salvadorian, it is terrifying,” she said, reflecting back to the civil war years when government repression ramped up and she fled. “In the beginning of 1980, it exploded. People my age were being arrested. I didn’t even know that we had any rights. We were being arrested, disappeared, not even being jailed, being killed. It is terrifying to me that we are going back to this.”

Kelley Dick calls out some of the names of those shipped from the U.S. to an El Salvadorian prison as part of the vigil for Kilmar Abrego Garcia outside the El Salvadorian Consulate, 5447 E. 5th St., in Tucson on April 16, 2025.

In that period, the U.S. government refused to recognize the abuses the Salvadoran government was committing, rejecting appeals for asylum from escaping Salvadorans. That’s what led the Rev. John Fife and others to start the Sanctuary Movement here in Tucson, bringing Salvadorans covertly into the United States for years. Now, El Salvador Pres. Nayib Bukele is rejecting appeals from people sent by the U.S. to El Salvador.

While the United States propped up right-wing governments in El Salvador during the civil war era, now it’s El Salvador’s turn to bolster ours, serving as a model of authoritarian governance for the USA. Bukele has governed his country under a “state of exception,” in which constitutional rights are suspended, for more than three years. He’s rounded up tens of thousands of prisoners, simultaneously slashing gang violence in the country and disappearing an unknown number of innocent people.

“He lifted the threat of the gangs,” said Fife, who still follows Salvadoran politics. “Now he’s an autocratic guy who’s aligning himself with Trump on everything from cryptocurrency to being the warehouse for anyone who Trump wants to deport.”

A mocking refusal

In that sense it’s fitting that it was Bukele who walked Pres. Trump across the threshold Monday in the White House, consummating our president’s pursuit of one-man rule by together defying the U.S. Supreme Court. Bukele mocked our entire system of government when he told a reporter he would not follow our Supreme Court’s ruling and send Kilmar Abrego Garcia, a Salvadoran mistakenly sent to prison there, back to the United States.

“I hope you’re not suggesting that I smuggle a terrorist into the United States,” Bukele said. “How can I smuggle a terrorist into the United States? Of course I’m not going to do it. The question is preposterous.”

No one has ever even accused Abrego Garcia of being a terrorist, but that sort of accusation is what sustains leaders like Bukele and Trump. The idea that they are imprisoning bad people distracts from the fact that, in this case, the real issue is that our president, with the help of Bukele, is violating a Supreme Court order.

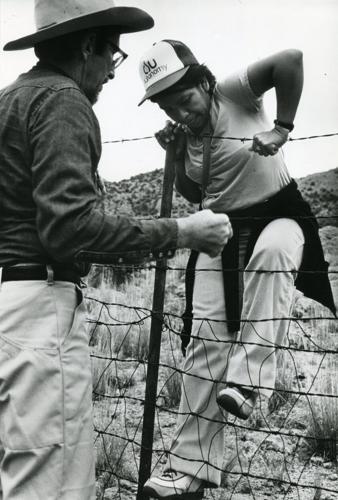

"Juana" climbs the desert border fence from Sonora, Mexico, into Arizona with the help of Jim Corbett, a member of the Sanctuary Movement during the summer of 1984. Photo from the 1984 series "Road to Refuge" documenting the travels of Guatemalan refugees from Mexico city to Tucson by means of an "underground railroad".

During the protest on East Fifth Street, many people held up signs with Abrego Garcia’s name and image, but it doesn’t really matter who the prisoner is. If the administration is going to ignore court dictates and label anyone they take away as a criminal deserving it, any of us could be taken away “mistakenly” and sent to a Salvadoran prison. I can’t imagine Bukele would sympathize with us any more than the U.S. government did with fleeing Salvadorans in the 1980s.

As Rodriguez, founder of a migrant-rights group called Salvavision, put it, “The case of this young man is not about him. It’s about all of us, citizen and non-citizen.”

The appeal to fear

Even though the principle, not the individual, is what matters, the appeal to fear remains strong. Bukele came to power in 2019 during a severe public-safety crisis, with gangs controlling and terrorizing much of his country.

These gangs, coincidentally, are also the fruit of the civil war. Salvadorans who fled to Los Angeles grew up in gang culture there and, when deported, brought it back to El Salvador, where it flourished.

Trump has tried to create the impression that a similar crisis exists in the United States, talking up the dangers of migrant criminals and gangs and portraying himself as the man who can protect us. But the difference in conditions is stark: In 2018, the year before Bukele was elected, the homicide rate in El Salvador was 51 per 100,000. In the United States in 2023, the year before Trump was elected, it was 5.7 per 100,000 people. Preliminary reports say it dropped here in 2024.

But politicians know that Americans don’t feel like crime rates are going down, and they aren’t going down everywhere either. In Tucson, homicide numbers are rising, and there are occasional shocking killings like the death of Jake Couch in Tucson, who was attacked randomly April 5 on a downtown street by a man with a hatchet.

The crowd of a few hundred wave their signs to passing vehicles at a vigil for Kilmar Abrego Garcia outside the El Salvadorian Consulate on April 16, 2025.

So naturally, politicians are tempted by Bukele-style crime crackdowns. In his policy of sending foreigners to prisons abroad, Trump even has had support from Arizona’s new U.S. Sen. Ruben Gallego, a Democrat. He told my colleague Emily Bregel that he supports sending foreign criminals to prisons abroad if their countries won’t accept them and if they get due process.

“Look, what Donald Trump did was set up a trap for Democrats to run into because, of the 500 they sent there, I’m sure 200 of them are actually hard-core criminals,” Gallego said. “Now, are we going to go run to the podium and defend and try to get those people back? No, absolutely not. What we should be highlighting are those mothers that have children being deported arbitrarily without any due process.”

This is a short-sighted and overly narrow perspective on the issue and the politics, in my view. The Trump administration will try to color any wrongly arrested person they wish to as a gang member, criminal or terrorist. Just as Bukele called Abrego Garcia a “terrorist,” Trump pointed to a photo of his hands with obviously photoshopped characters “MS13” on his knuckles as evidence he is a gang member. The photo was fake.

Raquel Gutierrez, a Salvadoran-American writer who lives in Tucson and attended the protest, put it to me this way: “They create the narrative they need.”

Authoritarian tradition

A crucial difference between El Salvador and the United States is that the Central American country has a long tradition of authoritarian governments, the Salvadoran historian Hector Lindo, an emeritus professor of history at Fordham University, says. And they’ve often not just been authoritarian but also “personalist,” led by a populist figure like Bukele and Trump.

Bukele’s rule, Lindo said in Spanish during a 2024 lecture, “Unfortunately, is very consistent with El Salvador’s trajectory.”

We don’t have the same tradition in the United States. We’re also about 57 times as populous as El Salvador.

“El Salvador is almost the size of New Jersey,” Rodriguez noted. “You’re able to control it because demographically it’s a small country. But you can’t do that to this country. We are a massive number of people. (People) will speak out.”

“If we don’t speak out, yes it is dangerous. Yes. But I have hope.”

And Rodriguez plans to continue speaking out, in a way that wasn’t possible in El Salvador during the civil war or now, under the Salvadoran flag on East Fifth Street.