The Citizens Clean Elections Commission is moving to ensure the next time you see a political commercial, you won’t have to guess who’s really paying for it or squint or speed-read to find out.

Existing laws already say political ads need disclosure of who bought the airtime or who paid for the newspaper ads, billboards and mailers.

But a new rule adopted last week adds the requirement that those disclaimers actually spell out the three largest sources of funds that bought the commercial. Gone will be the ability to simply tell viewers the ad they are watching was funded by a group identified only as something like “Arizonans for a Better Arizona.’’

The rule also details exactly how big the disclosure must be and how long it needs to be visible on air.

Tom Collins, executive director of the Arizona commission, said the panel is not acting entirely on its own.

He pointed out that voters in November approved a ballot measure designed to unmask certain political organizations who, until now, had been given permission by state lawmakers to hide the true sources of their funds.

Several groups that get involved in trying to influence elections, which had not provided such disclosure, were not happy with what voters enacted and have challenged the law.

But a Maricopa County Superior Court judge ruled the measure is constitutional. And a separate challenge in federal court has yet to be heard.

Details of the new rule

All that leaves the commission with the power — and the duty — to write the actual rule on what Arizonans will see and hear.

For television, the biggest source of campaign advertising, the new rule says any broadcast ads require the names of the prime sponsors to be disclosed, both on the screen and spoken, at the beginning or end of each commercial.

Candidates and political groups can get around that oral revelation if the written list is displayed for at least one-sixth of the time the ad is being aired. That means at least five seconds for a 30-second commercial.

The rule is also designed to ensure viewers will have a reasonable chance of reading the disclosure: It has to be at least 4% of the vertical picture height.

So, if you have a TV with a screen 20 inches high, the lettering will appear to be about eight-tenths of an inch.

Radio commercials are not exempt, with the sole requirement that the top donors be “clearly spoken at the beginning or end of the advertisement.’’

Anything delivered by hand or mail must have a “clearly readable’’ disclosure.

For billboards, the commission rules call for the same 4% standard set for TV, for the size of the disclosure.

Standard billboards are 14 feet high. That translates out to a disclosure about 7 inches in height.

How social media posts must comply

The rule also covers text messages and other social media posts.

Collins agreed it’s not possible to put all the required disclosure, like the top three funders, into many of those posts, given the fixed limit on the number of characters.

But what is possible — and what the rule will mandate — is the inclusion of a clickable link that will take the reader to a page with the required information. He said that has to be a website where the names of the top funders are immediately available, without readers having to first wade through other campaign rhetoric.

Collins acknowledged that strictly speaking, posts on X (formerly Twitter) and Facebook pages do not cost anything unless they are sponsored ads. But he said that does not exempt them from disclosure because there is an underlying cost of preparing the messages.

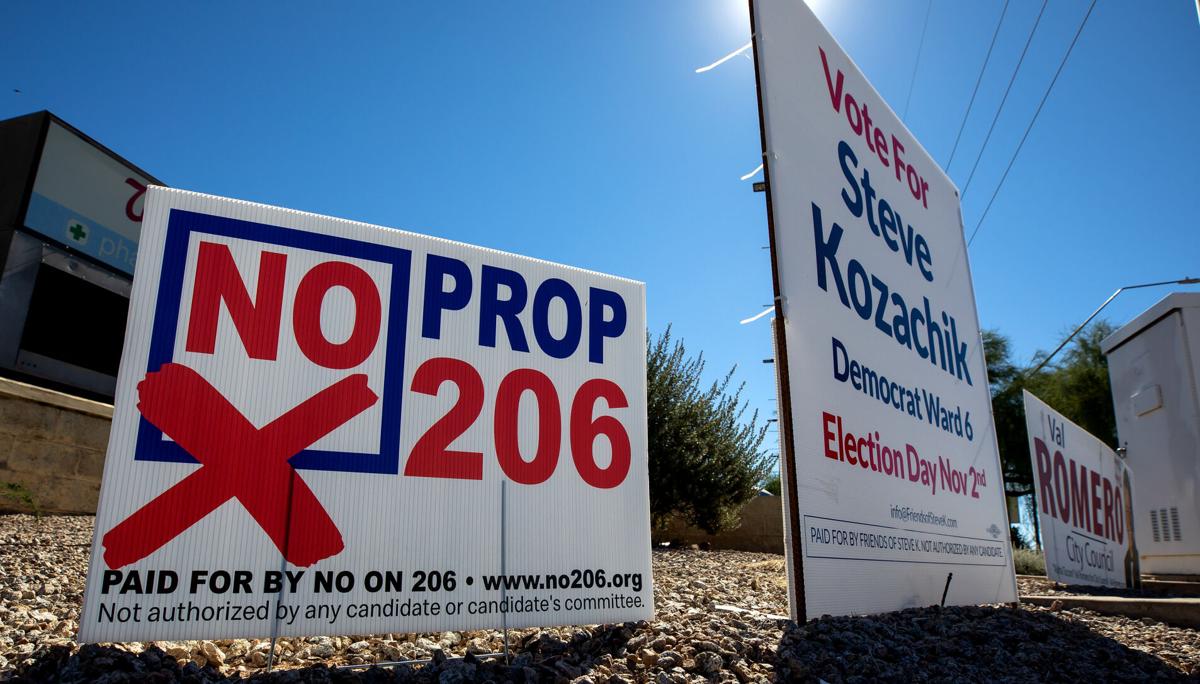

Not everything promoting candidates and political causes will have to be labeled, however. Supporters will still be able to produce and give out bumper stickers, pins, buttons, pens and other small items without having to worry about finding the space for disclosure.

Before adopting the rules, commissioners rejected a change sought by attorney Roy Herrera, whose firm tends to represent Democrats and their causes.

He argued that not everyone who gives to an organization wants to be associated with each of its communications or wants his or her funds used for that specific commercial. So, he sought to limit the disclosure to only those whose funds actually were used for that specific advertisement or commercial.

But commission staffers said there is nothing in state law that allows for someone who is among the top three donors to a group funding a campaign measure to opt out of having their name disclosed solely because they didn’t finance that particular message.

Commissioners also rejected some suggestions from the Campaign Legal Center, a national nonprofit that gets involved in issues of campaign finance laws.

“The proposed standards leave potential ambiguity as to what would qualify as, for example, ‘clearly readable’ or ‘clearly spoken,’’’ wrote Elizabeth Shimek, the organization’s senior legal counsel. She wanted the rules to state that a communication is not clear and conspicuous “if it is difficult to read or hear or if the placement is easily overlooked.’’

Commission staffers recommended against making that change, saying they were not aware of any abuses in the law that would indicate that’s needed.

Get your morning recap of today's local news and read the full stories here: tucne.ws/morning.