In a blistering letter, water officials in Arizona, California and Nevada recently took the federal government to task for failing to plan adequate measures to protect crucial Glen Canyon Dam infrastructure whose failure could significantly curb river flows to those Lower Colorado River Basin states.

The letter also faulted the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation for what it said is its failure to seriously consider the possibility that the four Upper Basin states may in just a couple years no longer meet century-old requirements for how much water they deliver downstream to the Lower Basin. The Colorado River Compact set minimum requirements in 1922 for how much water the Upper Basin states had to send downstream to the Lower Basin states.

The letter also blasted the bureau for its decision not to study in depth an alternative for managing the river that was proposed by the three Lower Basin states. The bureau’s failure to study that alternative goes against Reclamation’s “stated purpose and need, objectives and approach” to the alternatives it is studying and would violate federal requirements for how alternative options are supposed to be considered, the Feb. 13 letter said.

People are also reading…

In a blistering letter, water officials in Arizona, California and Nevada recently took the federal government to task for failing to plan adequate measures to protect crucial Glen Canyon Dam infrastructure whose failure could significantly curb river flows to those Lower Colorado River Basin states.

The letter is essentially an attack on the bureau’s ongoing study of five long-term alternative plans for managing the river to replace its current operating guidelines when they expire at the end of 2026.

Rather than specifically analyze proposals put forth by the Lower Basin states of Arizona, California and Nevada, or the Upper Basin states of Colorado, New Mexico, Utah and Wyoming, the bureau has incorporated elements of those two plans into other alternatives it’s now studying.

The new letter appears to open the door for a future possible Lower Basin lawsuit against the final regulations governing the river. The bureau’s failure to address these issues in planning for long-term operation of the Colorado River would, if it continues, violate longstanding federal environmental laws, the letter said. Those include the 1970 National Environmental Policy Act and the 1922 compact.

Also, Reclamation’s unwillingness to disclose how the Law of the River applies to each alternative and modeled scenario contradicts the agency’s own admission that it’s legally obligated to apply the Law of the River to future Colorado River operations, the letter said.

“Reclamation’s posture seems to be ‘kick the can down the road,’” said the letter.

It’s signed by Arizona Department of Water Resources Director Tom Buschatzke, California Colorado River Commissioner J.B. Hamby and Southern Nevada Water Authority General Manager John Entsminger.

Of particular concern is the bureau report’s “complete omission of compliance with the 1922 Colorado River Compact, the foundation of the Law of the River,” the letter said. The Law of the River is the collection of laws, regulations, court cases and other government actions that govern how the Colorado and its reservoirs are operated.

The compact requires the Upper Basin states to release 75 million acre-feet of river water over 10 years to the Lower Basin. The Lower basin states have also said — but the Upper Basin states disagree — that the Upper Basin states are also obligated to release an additional 7.5 million acre-feet over 10 years to carry out the U.S. obligations under a treaty with Mexico to deliver water to that country.

But as river flows have dropped over the past decade or so, the odds are rising that water releases to the Lower Basin will fall below minimum levels set by the compact, some experts have said. If low flows continue, “it is then reasonably foreseeable” that the Lower Basin states will issue a compact call to the Upper Basin states to curtail their river water use, the letter said.

The bureau should prepare in advance for a future compact call by moving water through the reservoirs before a call is required, to satisfy any potential, near-term compact obligations, the letter said.

“These anticipatory measures will be particularly important considering the need to protect critical infrastructure, the three water officials wrote.

Policy toward Lake Powell levels

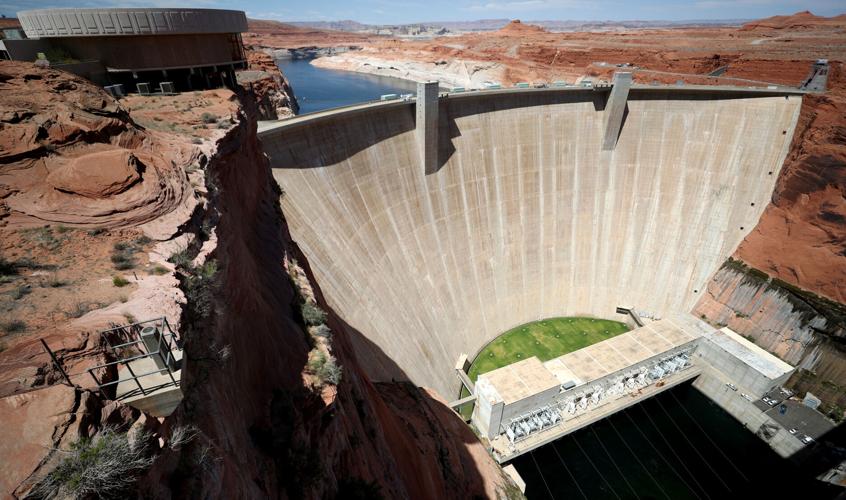

The Glen Canyon Dam’s outlet works — a set of long, narrow steel pipes at the base of the dam — are the most tangible symbol of the concerns raised by the Lower Basin states’ letter. The outlet tubes were designed more than a half-century ago to carry river water should Lake Powell drop too low for the water to pass through the dam’s turbines.

But last year, the bureau acknowledged that the outlet tubes would not stand up if used regularly and heavily in the event the lake falls below 3,490 feet. That’s the minimum elevation at which the dam can generate electricity that the federal government sells to more than 5 million people in seven states. When the lake falls below that level, the dam’s ability to send water downstream would get progressively worse until it hits “dead pool,” or 3,370 feet elevation, at which it couldn’t release any water downstream.

Reclamation has agreed to pay nearly $9 million for short-term repairs to the outlet tubes. It launched a study two years ago to try to find ways to re-engineer the dam so it can generate power and send more water to the Lower Basin even at low reservoir levels. But most experts agree that re-engineering the dam would cost billions of dollars, and little has been heard of that study ever since.

Instead, the bureau has pursued a course of trying to insure that Powell never falls below 3,490, so the outlet works don’t have to be used. Each of the five alternatives now under study says if Lake Powell is projected to fall below 3,490 feet, even after dams upstream of Glen Canyon release extra water, Powell’s releases would be reduced to protect 3,490 feet, the states’ letter said. In later months, more water would be released from Powell to make up for that cutback “if possible,” the letter quotes the bureau as saying.

‘Flying in the face of reality’

Two outside water experts, Eric Kuhn of Colorado and David Wegner of Tucson, said the Lower Basin states’ goals of getting the outlet works permanently fixed and having the new agreement address Colorado River Compact issues are politically unrealistic.

“That one doesn’t make sense to me,” Kuhn said of the letter’s advocacy of fixing the outlet works’ long-term problems in the near future.

While Kuhn himself has been among those saying in the past that the outlet works need more attention from the bureau, he said this month, “To fix the problem permanently — it’s a huge expenditure at a time when Reclamation is being told to cut expenditures. It’s flying in the face of reality.”

Wegner, a retired Reclamation official, agreed, saying “This is not a time for the bureau to initiate large programs.”

As for the Colorado River Compact, “Nobody wants to take that issue on. It’s opening Pandora’s box,” said Wegner, referring to long-expressed concerns that taking on the dispute over whether the Upper Basin is violating the compact could lead to endless litigation.

Kuhn termed the compact issue “a 50-50 deal” between the two basins that won’t be easily resolved. He pointed out that the compact itself contains no provision for a compact call to be made to force the Upper Basin to meet its requirements for downstream river water releases.

“Both sides have very valid arguments about the compact and different interpretations. In my view, asking the bureau to interpret the compact when states have been fighting over this issue over 80 years, it makes good publicity. ... But the Lower Basin states are asking the bureau to do something on which they’ve been unable to do, which is to reach common ground.”

However, the United States has a legal obligation to implement the Colorado River Compact, the Arizona Department of Water Resources told the Star in response to Kuhn and Wegner’s comments.

“While these legal questions have been unresolved for decades, we will not be able to ignore them over the next twenty years, absent a consensus agreement. Reclamation will, ultimately, have to take a position,” ADWR said in a written statement. “Even if Reclamation disagrees with the Lower Basin States’ Compact interpretations, that does not relieve Reclamation of the obligation to analyze any reasonable alternative.”

Two environmentalists applauded the new letter.

“Ignoring this problem poses great dangers for metropolitan areas in the desert Southwest. True river advocates are not going to cower during this moment. I tip my hat to leaders of the Lower Basin for having the fortitude to raise the issue,” said Kyle Roerink, executive director of the Great Basin Water Network, based in Nevada.

Longtime Arizona Daily Star reporter Tony Davis explains what "dead pool" means as water levels shrink along the Colorado River.

“Being silent will only guarantee that you don’t get what you want,” Roerink told the Star.

The new letter matches a point the group Save the Colorado has been making for months: that the bureau’s alternatives violate the Law of the River, said Gary Wockner, the Boulder-based group’s director.

“When the bureau released its five alternatives, we immediately looked at it and said all five violate the Law of the River, because they don’t let enough water out of Glen Canyon Dam when the lake is low to meet compact requirements.

“The Lower Basin states wrote exactly the same letter we were going to write, with the same specific legal citations” when it came time for the bureau to receive public comments on the alternatives it’s studying, he said.

“Now, I talked to our legal staff and said we don’t have to write it,” Wockner said.

‘Unnecessary reinvigoration of hostilities’

Asked by the Star to respond to the three states’ letter, the Bureau of Reclamation didn’t comment specifically but issued a statement through an agency spokesman, saying, “The Colorado River is essential to the American Southwest, and the Department of the Interior and Bureau of Reclamation are dedicated to providing life-sustaining water and harnessing the significant hydropower the river offers. We are actively engaging in dialogue with the Colorado River Basin partners as we work towards long-term operational agreements for the river after 2026. Throughout this effort, we remain committed to ensuring fiscal responsibility for the American people.”

Three Upper Basin water officials — Director Chuck Cullom of the Upper Colorado River Commission, Director Amy Haas of the Colorado River Commission of Utah and Becky Mitchell, the state of Colorado’s Colorado River commissioner — all declined to directly comment on the new letter.

A set of four tubes known as the “river outlet works” allow extra water to flow through Glen Canyon Dam. The flows are designed to take advantage of wet years and help wildlife habitats downstream. Reclamation has agreed to pay nearly $9 million for short-term repairs to the outlet tubes. It launched a study two years ago to try to find ways to re-engineer the dam so it can generate power and send more water to the Lower Basin even at low reservoir levels. But most experts agree that re-engineering the dam would cost billions of dollars, and little has been heard of that study ever since.

In a statement, however, Mitchell addressed the river dispute in general terms, saying, “We know that we get the best solutions in the basin when the states work together, so I am focused on building a broad consensus to address the risks on the River.

“The Upper Division States are committed to working towards supply-driven operations of Lake Powell and Lake Mead — this year’s hydrology is a stark reminder of why this is necessary. A sustainable approach will require all to live within the means of what the river provides.”

Anne Castle, a former assistant Interior secretary, criticized the letter, saying “I think it was an unfortunate and unnecessary reinvigoration of hostilities.”

Castle, who last month left her post as federal representative of the Upper Colorado Commission, declined to comment further. But Kuhn, an author and historian on water issues, said he’s heard the new letter had ratcheted up tensions among the basins’ water officials.

The states met within the last two weeks “and the tensions were higher,” said Kuhn, retired general manager of the Colorado River Water Conservation District in Glenwood Springs.

Tensions had previously relaxed a little bit after the Upper Colorado River Commission issued its refined proposal on Dec. 30, Kuhn said. The proposal offered “under some big caveats and a lot of ifs and buts” — to implement some conservation measures and put the saved water into Lake Powell for future release to the Lower basin, he said.

“A lot of people thought there was some progress there,” after that proposal came out, Kuhn said.