PHOENIX — Arizona's political redistricting plans are still a work in progress. But an organization that studies the fairness of redistricting nationwide likes some of what it sees developing here.

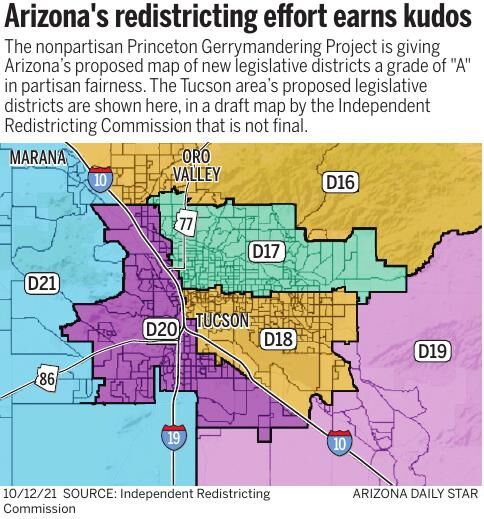

The nonpartisan Princeton Gerrymandering Project is giving the proposed map of new legislative districts a grade of "A" in partisan fairness.

Its researchers find that out of the 30 legislative districts, the lines give Republicans a sufficient edge in 14 to pretty much guarantee the GOP's nominee can win, with two others leaning that way. They also find that the map gives Democrats nine districts that should be safe for the party's nominee and five others with a Democratic leaning.

The researchers also give an "A" to the Independent Redistricting Commission's draft map for the state's nine congressional districts, finding a Democratic edge in three and a Republican edge in three others.

It is an analysis of what is available publicly, which is still an early version. Commission members meet again this week to continue making adjustments, with a goal of having something ready just before Christmas to then be used in the August 2022 primary and November general election, and for the remainder of the decade.

But the Princeton project is less impressed with the number of competitive districts now being contemplated, where candidates from either party have a chance of winning. And that is far different from partisan split.

Out of the 30 legislative districts, the project's analysts found just seven in the maps so far being considered where the margin of vote share between the parties is in a range where the vote could go either way. Only three of the state's nine congressional districts were listed in the "competitive zone.''

Put another way, whoever wins the partisan primary in 23 of the legislative districts would be a virtual shoo-in to take the seat in the general election.

And for Congress, three of the nine seats wouldn't be considered safe for either major party.

That rates just a grade of "C."

The 2000 voter-approved law creating the commission requires that, to the extent possible, it create as many politically competitive districts as possible.

But there are factors that could get in the way.

The law mandates that districts be pretty much equal in population.

For congressional districts, commissioners are shooting for about 794,500 residents for each.

Courts have provided a bit more wiggle room for legislative districts. But the goal here is about 238,000 for each of the 30 districts.

The law also requires commissioners to create districts that respect communities of interest and use county boundaries when possible.

Adam Podowitz-Thomas, the senior legal strategist for the Princeton project, said the commission should not be disappointed by the rating.

"From our perspective, C is good,'' he told Capitol Media Services on Monday. "C is an average.''

"Arizona is doing better than a lot of other places,'' Podowitz-Thomas added.

The process used here is much of the reason.

Before 2000, it was left up to state lawmakers to draw both the legislative and congressional lines. That often resulted in the majority party crafting maps that were advantageous to its interests.

It also sometimes led to incumbent lawmakers drawing potential political challengers into different districts, even from within the same party.

That year, voters approved creation of the Independent Redistricting Commission. It consists of two Republicans and two Democrats, each picked by elected party leaders. They, in turn, choose a fifth person, a political independent, to chair the panel.

Arizona is now in the third cycle of that process for drawing the lines.

"What we're seeing in states that are strictly partisan controlled is that whatever party is in control is sort of maximizing the number of 'safe' seats that it can generate,'' Podowitz-Thomas said.

In a broad general sense, much of what the draft maps show is no real surprise.

The fastest growth has been in Maricopa County, where population is up more than 21% since the last time the maps were drawn. Pinal County posted a 30.5% increase.

By contrast, Cochise and Santa Cruz counties lost population. And Pima County grew by less than 9%, less than the statewide 12% average.

So, to create districts of equal population and live within the numbers — 30 legislative and nine congressional districts — that means even more districts packed into urban areas to meet the population requirements. Conversely, it means large, sprawling rural districts putting geographically diverse communities into the same district.

It's not just rural areas that are affected by unequal population growth around the state.

For example, the draft congressional map divides Tucson between two districts. That is not unusual, as there is currently a similar split.

However, the proposed line is roughly north-south along I-10 and I-17, contrasting with the current maps, which include downtown Tucson and the University of Arizona in the western half.

But to get the 794,500 residents it needs, that proposed west-side district is drawn to range from Tucson all the way west to Yuma and then north to the western Phoenix suburbs of Buckeye, Glendale and Goodyear. That potentially dilutes the votes and influences of those living in the Tucson section of the district to elect lawmakers of their choosing.

That theoretically could be solved by moving the line between the districts to the east to take in more of Tucson. But then this district, which already takes in all of Cochise County, would be short of population.

That could be solved by moving sections of Marana, Oro Valley and southern Pinal County into the district. Only thing is, that would add more Republicans than Democrats, giving the GOP an edge.

And then there are ripple effects.

Marana and Oro Valley now are proposed to be in a district that sprawls all the way through not just Casa Grande and Apache Junction but into southwest Phoenix. Take away population to balance a Tucson district and the remaining district then needs to pick up more people elsewhere.

There are other issues.

One is trying to keep Native American tribes in the same congressional and legislative districts even as population growth in their areas have not kept pace with the rest of the state.

This is more than an academic goal. The Voting Rights Act generally forbids changes in state election laws that make it harder for minorities to elect someone of their choice.

There already is a legislative district with three lawmakers from the Navajo Reservation. Expanding that district to include large non-reservation areas could endanger that status and run afoul of federal law.

But here, too, any changes result in more ripple effects, such as putting Camp Verde and Cottonwood into the same district as Prescott, a linkage that does not now exist. Other options include whether and how to divide Flagstaff.

The Voting Rights Act provision also is likely to come into play as commission members work to ensure that the number of legislative districts represented by minority lawmakers is not reduced.

Tucson-based World View Enterprises plans to start flying tourists to the stratosphere in balloon vehicles by 2024. Video courtesy of World View.