Audubon might be synonymous with birds, but the group’s local chapter wants to distance itself from its namesake naturalist and his deeply problematic past.

The board of directors for the Tucson Audubon Society has voted to drop the Audubon name, citing “a legacy that causes pain, unease and distrust among partners and community members.”

The 75-year-old chapter of the national conservation group hopes to unveil its new name by early next year at the latest, after what it called a “collaborative process” to come up with something that “encapsulates who we are and what we do, while being inclusive and welcoming to all.”

John James Audubon gained fame in the first half of the 19th century for his colorful and detailed avian artwork and his pioneering quest to document all the birds of North America, namely by shooting them so he could paint them.

A portrait of John James Audubon taken a few years before his death in 1851 by famous American photographer Matthew Brady.

According to numerous historians and Audubon’s own writings, he was also a slave owner and an avowed white supremacist, who opposed abolition, desecrated Indigenous burial grounds to collect human skulls, and boasted about returning escaped slaves to their enslavers for their own good.

Audubon had been dead for decades when the first societies were formed in his name in the late 1800s, some of them by women seeking to stop the wholesale slaughter of birds for the feathers used to decorate fancy hats and other garments.

The National Audubon Society was founded in 1905 and now includes some 400 independent nonprofit chapters, making it one of the oldest and most-influential wildlife advocacy groups in the U.S.

The Scott's oriole like this one filmed near Vail is one of several birds that might be renamed. More of Jason Miller's wildlife videos can be found at Jason Miller Outdoors on YouTube.

Part of a flock

With its board vote last month, the Tucson chapter joined a growing list of two dozen other Audubon affiliates from San Francisco to New York City that have decided to rebrand themselves.

The labor organization representing National Audubon Society staff members has also disavowed the old name, announcing in February that it would refer to itself, at least temporarily, as The Bird Union.

But the national group has decided not to make a change, even after four years of public soul-searching that began in the midst of nationwide protests against racism and police brutality touched off by the murder of George Floyd.

“The (Audubon) name has come to represent so much more than the work of one person, but a broader love of birds and nature and a non-partisan approach to conservation,” said National Audubon Society board chairwoman Susan Bell in an announcement in March.

While the society must continue to “reckon with the racist legacy of John James Audubon,” Bell said the group’s best chance of protecting birds and their habitat moving forward is by maintaining its familiar brand.

Erica Freese is director of development and communications for the Tucson Audubon Society, which promotes birding, bird conservation and the protection of bird habitat at its Mason Center in northwest Tucson, its Paton Center for Hummingbirds in Patagonia and elsewhere.

Freese said local members had hoped that the national group would opt for a new name so the entire network of affiliates could make the change together. When National Audubon declined to act, she said, the local chapter decided to move forward on its own.

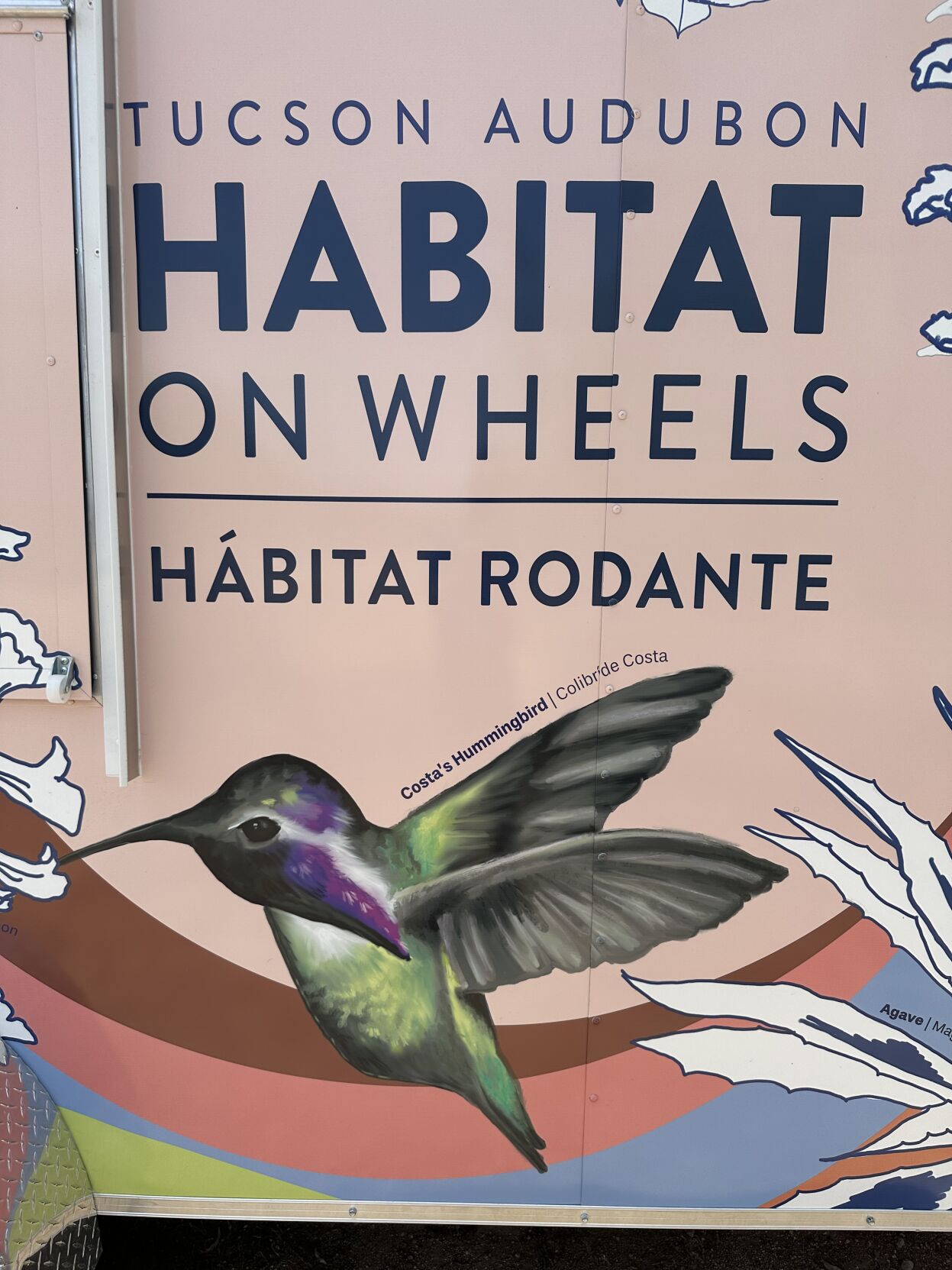

This trailer parked at the Tucson Audubon Society's Mason Center at Hardy Road and Thornydale Road is due for a new paint job. The local bird advocacy group is dropping Audubon from its name, and the bird's name might need an update, too, as the American Ornithological Society considers changing the common names of all North American birds named after people, including the Costa's hummingbird.

As the Tucson group explains on its website: “We are changing our name because birds and their habitats are facing critical threats, and saving them requires everyone’s involvement.”

The Audubon name is “a clear barrier for people who might otherwise become involved in or support our work and is detrimental to those already in our community,” the group states. “In order for our organization to have the greatest impact, we need the support of as many members, partners and the general public as possible.”

Who’s who

The reevaluation of John James Audubon comes amid a broader debate in the bird world about the use of any proper names in the common labels we affix to our feathered friends.

In November, the American Ornithological Society — keepers of the official list of English names for the continent’s birds — announced plans to relabel all species named after people to correct what it called the “historic bias” in how such titles were handed out and for whom.

As the ornithological society’s executive director and CEO Judith Scarl put it: “Exclusionary naming conventions developed in the 1800s, clouded by racism and misogyny, don’t work for us today, and the time has come for us to transform this process and redirect the focus to the birds, where it belongs.”

A Gambel's quail perches on a park bench at Tohono Chul Park. The species could eventually get a new common name under a plan by the American Ornithological Society to eliminate all eponymous bird names.

The move came after a petition drive by a group calling itself Bird Names for Birds in 2020, the same year the American Ornithological Society declared that a small Great Plains songbird previously named in honor of a Confederate Civil War general would henceforth be known as the “thick-billed longspur.”

The sweeping decision to drop proper names from all North American bird species has drawn criticism from some avian experts in the U.S. and triggered an outright revolt in South America, where nearly every member of the society’s South American Classification Committee bolted to join another bird-naming organization, the International Ornithologists’ Union.

The rift highlights the complexities involved in trying to name — and rename — winged creatures capable of migrating between continents and across hemispheres.

The society has since scaled back its ambitions.

The group originally announced plans to rename as many as 80 North American species during its first round of changes this year. Now its pilot program has been reduced to just six birds: the Bachman’s sparrow, the Inca dove, the Maui Parrotbill, Scott’s oriole, the Townsend’s solitaire and the Townsend’s warbler.

Four of those species — the dove, the oriole, the solitaire and the warbler — can be found in Southern Arizona.

Eventually, a host of familiar local birds could see their common names changed, including the Old Pueblo’s ubiquitous Gambel’s quail. Other candidates for new names are the Lucy’s warbler, the Cooper’s, Harris’ and Swainson’s hawks, and the Anna’s, Costa’s and Rivoli’s hummingbirds.

What’s in a name

Rebranding can be tricky business, according to Carolyn Smith Casertano, a public relations professional and a professor with the University of Arizona Department of Communication.

“You hope that people will go along with you, but sometimes it doesn’t really stick,” Smith Casertano said. “Your name is really your identity.”

She said Tucson Audubon will have to choose a new name that matches its mission and then communicate that change in a careful and thorough way. The birding and environmental advocacy nonprofit will also have to pay close attention to the details, such as making sure people searching online for Tucson Audubon are directed to the group under its new name instead.

“Certainly it’s a problem if people can’t find you,” she said. “They will have to work very hard to make sure that people still know they exist.”

An 1820s line drawing of John James Audubon.

Though a few people might be upset by the change and disagree with the reasons behind it, Smith Casertano predicts that a greater number will respect the Tucson chapter for its principled stand.

“Dropping the name sends a very powerful message,” she said. “I can’t imagine people walking away from the Tucson Audubon Society just because they changed the name.”