Wondering why Kamala Harris is listed ahead of Donald Trump on your ballot? Or vice versa?

Or Ruben Gallego versus Kari Lake?

It’s not a conspiracy. It’s the law. And it depends on where you live.

That’s despite claims by some people there’s evidence whichever candidate’s name goes first may have a marginal advantage.

What it comes down to is who won the last gubernatorial race in your county. A 1979 Arizona law says that determines ballot order for the next two statewide elections.

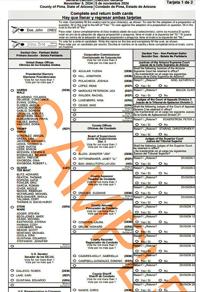

In 2022, Democrat Katie Hobbs outpolled Republican Kari Lake in Coconino, Maricopa, Pima, Santa Cruz and Yuma counties. So every partisan race on this year’s ballot in those counties, from president on down, lists the Democratic contender first.

It’s the reverse in the other nine counties, where Lake did better than Hobbs, even though the GOP candidate lost the race statewide by 17,117 votes.

Is it a fair system?

The first page of a sample Pima County ballot for the Nov. 5 election.

Democrats didn’t think so four years ago — just ahead of the 2020 election — when they noticed Republicans were set to be listed ahead of Democrats in all races in 11 of the state’s 15 counties, including Maricopa County, which has more voters than the other 14 combined. That was because Republican Doug Ducey beat Democrat David Garcia in 2018.

So they filed suit in federal court.

“For the past 40 years, the result has been the systemic favoritism of Republicans on the vast majority of general election ballots,’’ argued attorney Sarah Gonski on behalf of the Democratic National Committee.

She said it does make a difference.

“It is now well established that the candidate whose name appears first on a ballot in a contested race receives an electoral benefit solely due to her first position,’’ Gonski told U.S. District Court Judge Diane Humetewa. “Politicians and parties long strongly suspected as much, but this particular piece of political mythology has been confirmed by academics again and again, persuasively and, in recent years, definitively.’’

She cited data from Jonathan Rodden, a political science professor at Stanford University. He estimated the first-listed candidates get an average advantage of 2.2 percentage points.

That advantage could reach 5.6 percentage points, Rodden said.

None of that swayed Humetewa. The problem, the judge said, started with the legal ability of the challengers to raise the issue.

She said anyone seeking federal court intervention must demonstrate “a personal stake in the outcome,” showing they would be injured “in a personal and individual way.’’

That wasn’t the case here, she said.

“The harm that plaintiffs allege is not harm to themselves, but rather an alleged harm to the Democratic candidates whom they intend, at this juncture, to support,’’ Humetewa wrote.

She said a candidate’s failure to get elected does not injure those who voted for that person.

Nor, the judge said, can they show other harms due to the ballot-order law.

“They do not order that the ballot order statute prevents them from casting a ballot for their intended candidate, nor do they argue that their lawfully cast votes will not be counted,’’ she said. She brushed aside any arguments that some people were having their votes for the candidates diluted because others were simply picking the first name they saw.

“Plaintiffs will not be injured simply because other voters may act ‘irrationally’ in the ballot box by exercising their right to choose the first-listed candidate,’’ Humetewa wrote.

She wasn’t impressed by the Democrats’ proposed solution, either: Rotating the position of names on the general election ballot — but only between the Democrats and Republicans.

“Their definition of ‘fairness’ does not require rotation of independent party candidates, write-in candidates from the primary election, or other third-party candidates in their ballot scheme, meaning that those candidates would never be listed first on the ballot,’’ the judge said.

In addition, Humetewa said in her 2020 ruling there was no actual proof the system impaired the ability of Democrats to get elected to statewide office. Exhibit No. 1, she said, was the 2018 election of Kyrsten Sinema — then a Democrat — to the U.S. Senate over Republican Martha McSally.

As it turned out, more recent history has backed Humetewa’s conclusion the law is not discriminatory and is not a handicap for Democratic candidates.

In the 2022 election, Democratic candidates won statewide races not only for governor but also for secretary of state and attorney general.

There has been no further effort by the Democrats to overturn the system.

Democratic vice-presidential candidate Tim Walz in Tucson for early-voting rally, Oct. 9, 2024