Self-styled wealth guru Kevin Easterly of San Diego would be breaking the law in his home state if he bought an apartment building and imposed a huge rent hike on tenants.

But it’s perfectly legal in Tucson, where he and his partners have been playing a sort of real-life Monopoly game: buying and repainting aging apartment buildings, and raising rents 50% or more to boost the property’s value and refinance for more than they paid, public records and Easterly’s social media posts show.

Once featured in an Instagram video called “How to Flip Apartment Buildings,” Easterly recently partnered to buy a senior citizens complex at 1511 N. Craycroft Road that catered to older people on fixed incomes — until he raised rents by 52%.

“It’s a very sad place around here,” said former tenant Nan Abrams, 74, who spent the recent holidays packing up the one-bedroom unit she used to rent for $579 a month. She moved out a few weeks ago, a month after receiving a lease renewal notice that said her new rent would be $880, a $301 increase. Other tenants said they were forced out when management declined to renew their leases.

Abrams, who is staying with friends for now, said she’s worried about her former neighbors, some of whom have health issues that could make moving difficult.

“One of my neighbors uses a wheelchair and needs oxygen. I see some of these people and wonder ‘Where are they going to go?’”

Big rent hikes can be disastrous for elderly tenants no longer in the workforce, said Jim Murphy, president of the Tucson Housing Foundation and chair of the Affordable Housing Alliance for Older Adults, a group studying the region’s senior housing shortage and what might be done to address it.

“An older person may have less of a chance to recover from something like this. A younger person might have the ability to go out and earn some more money,” he said.

Flipping senior citizen apartments “may be legal, but it’s certainly not moral,” he said.

Easterly, 41, is not widely known in the real estate investment field with 205 followers on Facebook, 827 on Instagram and 13 on Twitter — this in a world where big names have millions of followers.

Even so, he now co-owns four Tucson apartment complexes with nearly 160 units between them, all purchased in less than five years through four limited liability companies he registered in Arizona. In each case, he used a system he described in the apartment-flipping video as “rehab, kick the tenants out and raise the rents.”

Easterly could not be reached for comment for this story despite more than 20 attempts over a two-week period. (See box)

Tucson City Councilman Steve Kozachik, whose Ward 6 is home to the Craycroft Road seniors complex, called the 52% rent hike “nauseating.

“This is predatory capitalism and it is totally without a conscience,” he said. “It’s a telling example of what’s happening in our real estate market. Tucson is vulnerable because our real estate prices are relatively low compared to the rest of the nation.”

Murphy said the tenants Easterly is displacing will have a tough time finding affordable quarters in a city where more than 3,000 people already are on waiting lists for publicly-funded apartments geared toward seniors and those with disabilities.

In California, it’s illegal for a landlord to raise rents by more 10% a year. But Arizona has no such limits, nor are there limits in neighboring Nevada, where Easterly co-owns apartment buildings in Las Vegas and Henderson similar to his Tucson properties, according to his San Diego website.

Raising rents is key tactic

Easterly aims to eventually become a “billionaire, with a B” and raising rents is one of his key tactics, his social media posts show. He calls it “forced appreciation,” a way to drive up a property’s value faster than would happen by market forces alone.

It typically involves cosmetic improvements such as new exterior paint and landscape gravel and rent hikes in the 50% range, his posts show. The rent increases are critical, he explained on the apartment-flipping video, because a rental property’s value is closely tied to how much income it generates — a number banks use in lending decisions.

Easterly’s first Tucson purchase was in 2017 when he teamed with three other California investors, public records show. They put $350,000 down on a $1 million, 30-unit apartment complex at 3653 E. Second St., and raised rents there by 53%, from $425 to $650 a month.

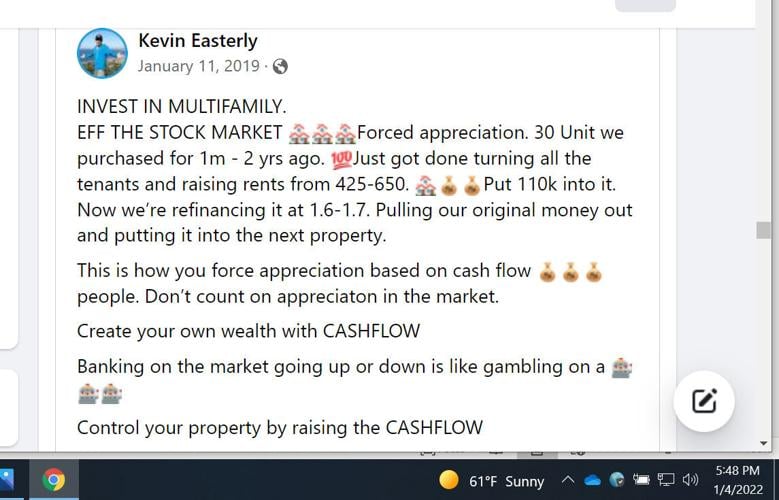

Eighteen months later, Easterly announced plans to refinance the complex for up to $1.7 million — 70% more than he paid — and use the proceeds as a down payment on another apartment complex. He described the process this way in a January 2019 Facebook post:

Social media posting on a public Facebook page by Kevin Easterly.

“EFF THE STOCK MARKET. Forced appreciation, 30 units we purchased for $1m — 2 yrs ago, Just got done turning all the tenants and raising rents from 425-650. Put 110k into it. Now we’re refinancing at 1.6-1.7 . Pulling our original money out and putting it into the the next property.

“This is how you force appreciation based on cash flow people. Don’t count on appreciation in the market.”

Later that year, Easterly and partners put $600,000 down on a $1.8 million, 36-unit complex at 3949 Monte Vista Drive, property transfer records show.

Last year they bought two more back-to-back in August and September: a 52-unit at 3493 E. Lind Road for $3.6 million with $1 million down and the Craycroft Road seniors complex for $3.2 million with $960,000 down.

Each of the Tucson complexes are 30 to 60 years old, built between 1963 and 1992. In the apartment-flipping video, Easterly refers to them as “B- and C-class” properties. It isn’t clear from public records if any others besides the Craycroft Road complex were exclusively for older adults ages 55 and up.

Solutions under study

So far there’s no end in sight for the apartment-buying spree. But efforts are underway to try to mitigate some of its worst effects on Tucson seniors.

The Affordable Housing Alliance for Older Adults is in the process of creating a Pima County-wide housing plan for seniors, said Murphy, the group’s chair. A long list of ideas is being looked at including tiny homes, container homes, a home-sharing database that pairs willing renters with would-be roommates and converting motels and vacant schools and business space into lower-cost senior living space.

It’s hard to say with any accuracy how many local seniors don’t have access to affordable housing — defined by the federal government as housing and utilities costs that, when added up, are less than 30% of monthly income. Murphy said it’s hard to track need by age group because many local households — around 25% — are mixed, with older and younger people under the same roof.

Nan Abrams moves boxes inside her kitchen to make more room for packing inside her apartment in Tucson. She is moving out after a 52% increase in rent.

Murphy pointed to one improvement that’s already inching forward: Tucson City Council’s recent decision to allow “accessory dwelling units” — more commonly called casitas or granny flats — on many more residential properties. But such changes don’t happen quickly, he said, noting the council decision took more than a year of study and discussion.

Nonprofit real estate developers are stepping up too. Later this year, La Frontera, a Tucson agency that provides social services for those with low incomes, plans to open a 120-unit seniors housing complex on North Oracle Road near West Drachman Street.

Murphy said he’s hopeful more changes are on the horizon now that local lawmakers seem more attuned to affordable housing issues — and elder housing in particular.

“I don’t know if we can solve the problem,” Murphy said of the shortage. “But I do believe we can make a dent in it.”