Michael and James Abatti match nobody’s definition of environmentalists.

The Abattis and their forebears have farmed heavily in Southern California’s Imperial Valley for a century or more. Growing alfalfa and winter vegetables, they have thrived economically on their use of federally subsidized water delivered from the Colorado River. Michael Abatti, in particular, was described as a “farm baron” in a 2018 investigative profile by the Palm Springs Desert Sun of his “enormous influence over the desert’s Colorado River water, agriculture and energy.”

But now, the Abattis have become the first non-environmentalists in more than a quarter-century to formally advocate for a study of decommissioning the river’s Glen Canyon Dam.

Decommissioning the dam could mean altering the structure enough that it would no longer hold back water in Lake Powell or generate electricity. Instead, river water would flow directly downstream into the Grand Canyon and to Lake Mead, where it would be stored for future delivery to the Lower Colorado River Basin states of Arizona, Nevada and California.

Decommissioning Glen Canyon Dam could mean altering the structure enough that it would no longer hold back water in Lake Powell or generate electricity. Instead, Colorado River water would flow directly downstream into the Grand Canyon and to Lake Mead, where it would be stored for future delivery to Arizona, Nevada and California.

The Abattis made their comment in a letter last month to the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, which is in the early stages of preparing an environmental impact statement on how to revise operating guidelines for the Colorado River and its reservoirs, which must be done before they expire in 2026.

“Past proposals by environmental groups to decommission Glen Canyon Dam or to operate the reservoir without power production as a primary goal can no longer be ignored and must be seriously considered in the EIS,” the Abattis wrote, along with an engineer, Craig Morgan. “The evaporative losses occurring in Lake Powell are significant, given the demands on the Colorado River system, and must be taken into account.”

The over-allocated Colorado and its Powell and Mead reservoirs have dwindled drastically due to drought and climate change, and the lakes are barely more than a third full. Competition for water is now pitting the two lakes against each other in the eyes of environmentalists and some users.

The Abattis’ letter was one of three sent to the bureau, as it prepares to start its environmental analysis, that a Colorado environmental group, Save the Colorado, said had “Glen Canyon Dam in the crosshairs.”

Another of those letters, from water agencies in Arizona, Nevada and California, urged the bureau to study modifying Glen Canyon Dam so it can continue releasing large amounts of water even if its water elevations keep falling. A similar suggestion came in a separate letter from the Central Arizona Project, the canal system that brings Colorado River water to Arizona farms and cities.

Recently, the Interior Department, Reclamation’s parent agency, “took actions to adjust operations at Glen Canyon Dam” to reduce the risks to infrastructure there, wrote CAP General Manager Brenda Burman. She was apparently referring to last-minute cuts the department made in releases in 2022 from Powell to keep the lake from falling so low that it couldn’t generate power or release enough water downstream later.

“To reduce risks to infrastructure that may arise from decreasing elevations, a comprehensive review of Glen Canyon Dam and improvements that can be made to enhance its operational capacity must be undertaken to avoid such reactive actions, and to ensure that water can safely pass through the dam at low elevations,” Burman wrote.

Another letter, from the CAP and two urban water districts, Southern California’s Metropolitan and the Southern Nevada Water Authority, made a point of urging the bureau to insure that Lake Mead has enough water to meet “public health, safety and welfare needs” during low water conditions. But the letter “ignored” Lake Powell, although Powell supplies most of the river water that goes to Mead, said Gary Wockner, Save the Colorado’s director.

In a separate letter to the bureau, however, CAP’s Burman did urge the bureau to order strong enough reductions in river water use to protect both major reservoirs.

Metropolitan Water District’s spokeswoman Rebecca Kimitch took issue with Wockner’s characterization of the three agencies’ position.

While insuring that there’s enough water to serve Lower Basin cities requires keeping Lake Mead’s levels high enough, “there should be no inferences made about our position on other reservoirs in the Colorado River system that we don’t directly get water from,” Kimitch wrote in an email to the Star.

“A huge game changer”

Outside water experts’ reactions to the significance of these comments range widely.

Professor Jack Schmidt, a retired Utah State University water researcher, called the Abattis’ letter, for one, a “huge game changer.”

The fact that it’s coming from anyone other than an environmental group “is incredibly significant,” said Schmidt.

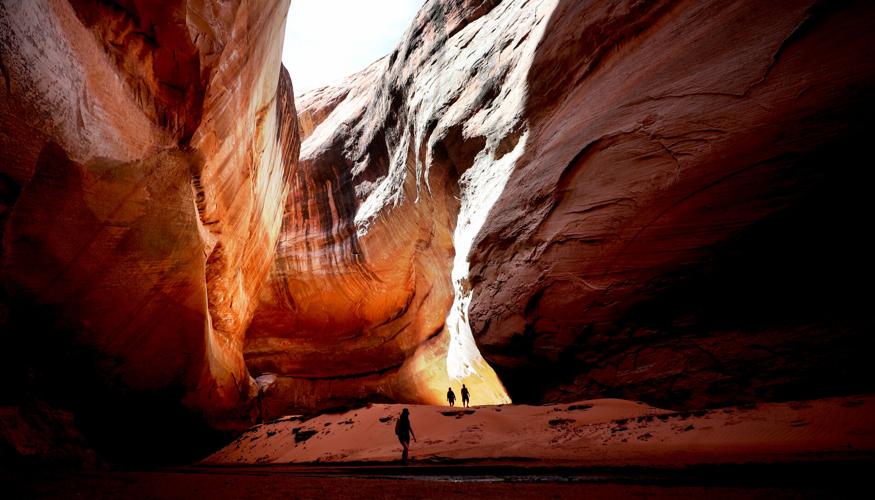

Receding water levels of Lake Powell are shown at Glen Canyon Dam. The over-allocated Colorado River and its Powell and Mead reservoirs have dwindled drastically due to drought and climate change, and the lakes are barely more than a third full. Competition for water is now pitting the two lakes against each other in the eyes of environmentalists and some users.

“The paradigm of the American West has always been the maintenance of the facilities that were constructed” to store and move water, said Schmidt, the just-retired director of Utah State’s Center for Colorado River Studies. “It was considered complete heresy and no one in the water supply community would have ever have acknowledged or accepted the notion of decommissioning the dam.”

The Abattis’ letter was triggered probably less by the work of environmental groups, and more by the continued decline of river runoff in the Colorado Rive watershed, he added.

“It’s the realization that Powell and Mead together may never be full again. If not, the thinking is, we oughta seriously consider what is the best place to store water,” Schmidt said.

One expert who doesn’t attach much significance to any of the comments, however, is Jeff Kightlinger, a former general manager for Metropolitan Water District who recently was hired as a consultant for the Imperial Irrigation District, where the Abattis operate.

Speaking of the state and urban water agencies’ comments, he said: “These are all just people laying out things they want to see protected. The scoping for the environmental impact statement is really a broad document.

“It’s just the usual positioning. The Lower Basin districts know that the Upper Basin will talk about protecting Lake Powell so they talk about protecting Lake Mead,” Kightlinger said. “They’re not saying tear down Glen Canyon Dam. They’re saying protect Lake Mead. They just want to protect their own interests.”

Upper Basin states — Colorado, Wyoming, New Mexico and Utah — have always said the dam is needed to ensure they have enough water in Powell to meet their obligations under the Colorado River Compact to make sure the Lower Basin is adequately supplied. The river starts in the Upper Basin; the dam is at the Utah-Arizona border; Powell is upstream of the dam, mostly in Utah, and Mead is downstream at the Nevada-Arizona border. The Grand Canyon connects the two lakes.

Professor Elizabeth Koebele at the University of Nevada-Reno agreed with Schmidt that the Abattis’ comments are significant because they seem to be the first signal that a coalition could be built between environmentalists and Lower Basin farmers around Glen Canyon Dam issues.

“As someone who studies collaboration in natural resources, any time one of these ‘strange bedfellow’ coalitions starts, even as something small, it piques my interest,” said Koebele, an associate political science professor. “But unless it picks up steam and gets more ag involvement, decommissioning Lake Powell seems far from a serious argument.”

She added, “We need to remember that the letter came from two growers, not the IDD (Imperial Irrigation District) or California as a whole.”

Plus, the three Lower Basin states’ letter clearly suggests “evaluating how to “manage Lake Powell and Lake Mead operations to reduce the risk of reaching critical elevations in either reservoir,” suggesting the expected maintenance of Lake Powell, Koebele said.

Dave Wegner, a retired Reclamation engineer who has worked with the Glen Canyon Institute as a founding trustee, characterized the various comments on Lake Powell and the Glen Canyon Dam as “chess moves”.

“They’re setting the stage for in-depth discussions starting now. You start big, and find where the collaboration or consolidation can occur. Are they serious? Yeah, they are putting out ideas, about what we should be doing in this stage in the process.”

Glen Canyon landscape vs. other values

Decommissioning Glen Canyon Dam has been a prime goal of a group of environmentalists living across the Colorado River Basin who formed the Glen Canyon Institute in 1996 to push for it.

A year later, a former Reclamation commissioner and congressional aide, Dan Beard, became the last non-environmental activist to advocate for decommissioning the dam — until now.

Those who favor removing the dam want to restore Glen Canyon, which to them is an almost mystical collection of grottoes, sandstone formations, cultural sites and riparian groves, to the way it looked before it was inundated by Lake Powell when the dam was built.

Sightseers explore the formation known as Cathedral in the Desert in Glen Canyon National Recreation Area, Utah, in 2022. The cathedral has reemerged after being submerged for decades by manmade Lake Powell, which is now receding. It's part of the landscape that would completely reemerge if Glen Canyon Dam is decommissioned and Powell is drained.

Western water officials have unanimously disdained the idea, most commonly because they say the dam is needed to store enough water in wet years to insure that in drier years the Lower Basin states get enough water.

They also have pointed to the dam’s generation of enough electricity to serve more than 5 million people, many of them Native Americans including Navajos, living in seven western states including Arizona.

Several other leading environmental groups, including the National Audubon Society and American Rivers, also have not gotten on board with the idea.

But in their letter, the Abattis not only spoke out in favor of studying decommissioning, they also opposed the idea of emphasizing power generation as an important factor in operating Glen Canyon Dam.

They noted that the 1922 compact said river water “may be impounded and used for the generation of electrical power, but such impounding and use shall be subservient to the use and consumption of such water for agriculture and domestic purposes and shall not interfere with or prevent use for such dominant purposes.”

They also said the bureau should consider the need to retrofit the dam. One idea would be to drill bypass tunnels through the dam’s sandstone abutments, so it can pass water downstream through the structure even when water is running too low to pass through the dam’s turbines.

The Glen Canyon Institute and Living Rivers were among the first entities to make such an argument in a study released in August 2022.

Kightlinger said he doesn’t think anyone at the Bureau of Reclamation would argue with the view that “we have to find a way to get water through the Glen Canyon Dam at low elevations.”

The bureau is now conducting a multi-year study on that subject that began in 2022. Various outside experts have said overhauling the dam could cost $500 million to $3 billion and take a decade to complete.

Evaporation is an issue

The concern the Abattis raised about evaporation at Lake Powell is the subject of a long, unsettled debate.

In 2016, Schmidt conducted a major study that concluded putting all of Powell’s water in Lake Mead would trigger “no change” in total evaporation. He reached that conclusion because there’s large, natural variability in how much evaporation occurs at Powell every year, and because data on the amount of evaporation there is “outdated,” going back to the 1970s.

Since then, however, the federally funded Desert Research Institute in Nevada has been conducting a detailed analysis of evaporation data in Lake Powell. With that data in hand, “now we can make a no nonsense decision on the magnitude of savings,” Schmidt said. “What Reclamation and the (computer) modelers will do is, they’ll say if we preferentially store in Mead, what is the evaporation rate in Mead? What is the rate in Powell? They can evaluate if there is a tradeoff.”

In a paper Schmidt wrote on the Colorado over the summer, he also concluded that despite others’ views that the dam is needed to insure enough water is saved to meet the Upper Basin’s legal commitment to release water to the Lower Basin, “For purposes of water management, it does not matter whether water is stored in Lake Powell or in Lake Mead.”

He noted that “there are no significant (human water) uses in the 400 miles of the Grand Canyon separating the two reservoirs.”

“No one says that there is an amount of water that every year has to be precisely released from Powell to Mead,” he said. “Whatever the number is agreed upon, on average, that number has to go from Powell to Mead. It can be released in a highly variable way or in a consistent way.”

The study warned, however, that “environmental tradeoffs will exist whether you put all the water in Lake Mead or Lake Powell.”

While keeping less water in Powell would allow the pre-dam Glen Canyon landscape to recover, emphasizing storage in Lake Powell would allow continued hydropower production there. he said.

It would also allow periodic releases of flood-like flows carrying sediment to restore sandbars and beaches along the Grand Canyon floor, he said. And it would help stabilize the Grand Canyon fish population for various reasons, he said.

But on the flip-side, emphasizing storage in Powell would “re-inundate valued portions of Glen Canyon that have recently been exposed” as Powell’s water levels sink. These include the massive pink and orange sandstone beauty called Cathedral in the Desert.

Because of uncertainties about the various tradeoffs, the National Audubon Society’s Jennifer Pitt said she’s not ready to take a position on whether Glen Canyon Dam should be decommissioned.

“I haven’t seen an analysis of what decommissioning the Glen Canyon Dam would do to the Grand Canyon, and I haven’t seen an exploration of how one might manage the two reservoirs as one in terms of impacts on resources at Glen Canyon. I’d like to see those analyses and understand the trade-offs,” said Pitt, Audubon’s Colorado River program director.

Decommissioning unlikely in short term

Alan Boyce, who farms dates, lemons, organic vegetables and “a little alfalfa” in the Yuma area and in the Imperial Valley, knows the Abattis and says he has some sympathy with their view of Glen Canyon Dam.

Two prominent growers in Southern California's Imperial Valley, whose irrigation district gets Colorado River water, have now suggested the federal government should study decommissioning the river's Glen Canyon Dam.

He describes them as “smart, outspoken, and all pretty darned good at what they do. They’re defending their livelihoods.” (The Abattis didn’t respond to requests for interviews.)

“Running two reservoirs the way we are is a way of maximizing evaporation. It’s kind of nuts,” said Boyce.

He added that he thinks the federal government should keep the dam in place but design it so it can release water even when Powell is at very low levels, so that Mead can be relatively full.

But he said he doesn’t expect to see the dam fully decommissioned anytime soon.

Former Reclamation engineer Wegner agrees that decommissioning the dam is very unlikely now. “I don’t see that happening in the next three years,” when the river’s federal operating guidelines must be updated. “Maybe the next 20 but not the next three.”

It’s not a huge reach to think the Lower Basin states and cities can get the feds to put more emphasis on protecting Mead in the next three years, he said, but “knowing the political process, knowing the Congress we have, decommissioning, it’s just not there.”

Longtime Arizona Daily Star reporter Tony Davis explains what "dead pool" means as water levels shrink along the Colorado River.