One giant saguaro lies prone, with two huge trunks jutting out from a thick set of roots running parallel to the ground.

Another still stands but it’s been sheared off at the top.

Two big arms are dangling down from a third saguaro, their tips touching the ground.

These are among about 1,200 saguaros that were toppled or sheared during a late August windstorm at Saguaro National Park-West, National Park Service officials have concluded.

On Tuesday the park service finished a count of the fallen saguaros that spanned nearly two weeks, required as many as 12 counters at a time and discovered downed and otherwise damaged saguaros in a large swath of the park, concentrated in the Avra Valley west of the Tucson Mountains.

Of those 1,200 saguaros, about 15% remain standing but had their tops sliced off, said Don Swann, a National Park Service biologist who led the count. A much smaller percentage lost arms but still stand, and a few more are now leaning over when they stood straight before, he said.

This is the second largest known “blowdown” of saguaros in the Tucson area in recent years, behind one 11 years ago that felled about 2,000 in Ironwood Forest National Monument northwest of Tucson.

The latest incident is not by itself a major threat to the saguaro population in the national park, which has about 2 million saguaros total in its two units bookending Tucson, about 1.4 million of them living in the west unit.

And while the lack of propagation of young saguaros, possibly due in part to human-caused warming, is a possible threat to the cactus’ future, the area of Saguaro Park-West where the blowdown occurred has some of the best rates in the park.

But an expert on monsoons, University of Arizona researcher Christopher Castro, says human-caused climate change could have been a factor in the storm that blew down the saguaros. His statement is based on the pattern of growing intensity of monsoon storms in the Southwest over the past 20 years. If it turns out that climate change is helping cause these events, more could happen if the climate continues warming as most climate scientists predict it will, he said.

We will need more data on more events over a longer period to be able to determine climate change’s impact on saguaro blowdowns, however, said Bill Peachey, a geologist who has studied saguaros for more than a quarter-century in the Tucson area.

A group of volunteers and staffers from the National Park Service are collecting data on a saguaros that were blown down in Saguaro National Park-West during an Aug. 22 windstorm.

It’s known that there have been 10 to 12 saguaro blowdowns in the Avra Valley since 2010, but there’s little or no data on such events going back any farther, he said.

“One of our purposes today is to come out and map this area and get a sense of how big the saguaros area and what direction they fall,” said the park service’s Swann as he stood next to a large fallen saguaro whose thick root structure jutted into open air.

“This is an issue that seeks out saguaros and causes mortality. We don’t now how big of a deal it is because it’s not been very well studied,” he said.

Ben Wilder, former director of Tumamoc Hill’s Desert Laboratory and now a private biological researcher, said he would rank wind-driven blowdowns last on a list of threats to saguaro populations. It would come after the threats from lack of propagation; drought; heat; and fire that’s triggered by buffelgrass and other mostly invasive grasses that readily ignite, he said.

If it turns out climate change is a factor in the blowdowns, that would increase their potential threat to saguaro populations, but they would still rank at the bottom of his list, said Wilder, now founder and director of the nonprofit Next Generation Sonoran Desert Researchers.

While the blowdowns could grow more common with climate change, he still sees them as “infrequent, episodic events,” compared to more existential threats such as drought, heat and invasive grasses.

Soil wet from series of storms

The count started the day after the high winds blew through the park, when, Swann said, “I got a call from a maintenance guy who said he had to pull a couple of saguaros from Kinney Road.” Kinney is Saguaro-West’s main drag, cutting through its core area and leading to its Red Hills Visitor Center.

By the time the tally was finished, the fallen cacti were found in an area whose north boundary lies just north of the intersection of Kinney and Sandario roads and whose east boundary is the Tucson Mountain slopes. Fallen saguaros were seen almost to the park’s west boundary and to Fort Lowell Road on the south. The area covers less than a square mile.

Peachey said he also saw fallen saguaros on private lands west of the park. But the park service lacked permission from landowners to enter those areas.

Nobody has records of how windy it got during the blowdown at the park, but 62 mph winds were recorded at Tucson International Airport at about 4:30 that afternoon.

It’s not known why the blowdown occurred where it did, other than much of the area has soils that are a little softer than normal. Most of it occurred in bajadas, areas that sloped from the mountains above down to the floor of the Avra Valley, Peachey said.

Another contributing factor was that a series of storms preceded and foreshadowed this event. Thunderstorms hit the Tucson metro area on Aug. 16, 18 and 21 as well as on the 22nd when the cacti blew down.

“Every one of these events I’ve seen so far have followed good rain or several days of rain, with the ground damp or soaked,” Peachey said. “All of them were preceded by wet soil or damp soil conditions.”

Can’t replant them; internal damage

On the last day of the saguaro count, Sept. 12, Swann led a reporter around a sloped area east of the park’s Desert Discovery Trail, less than a mile north of the visitor center.

The saguaro counters worked individual transects — specific areas laid out for scientific study — of a little more than 60 feet wide and up to a mile long.

Swann started by walking up a hillside east of Kinney. The soils there were rocky, offering saguaros more stability than finer soils farther downhill, where the vast majority of the downed saguaros landed.

Later that day, several counters, including another Saguaro Park staffer, an intern, several volunteers and Peachey, who served as an adviser to Swann, ventured into flatter ground to the west, containing finer soils that don’t hold roots as securely as rockier soils. Working in that area, one person alone turned up 40 fallen saguaros, far more than they found on the rockier slope areas.

When on the rockier hillside, Swann encountered a prone saguaro, about 20 feet long, its root upended and its top wearing a crack.

This one is at least 100 years old, as are the majority of the fallen saguaros, which are “more vulnerable,” Swann said. While a few of the downed saguaros are less than six feet tall, the majority are 18 feet to 24 feet, he said.

“People ask, ‘Do we replant them?’ They have internal damage. There’s nothing we can do to save them,” he said.

Instead, the saguaros are left to decompose and draw “a large number of different kinds of insects.”

David Rabb, a volunteer, walks further into the desert after collecting data on a saguaro that was toppled in Saguaro National Park-West during the August windstorm.

“A saguaro is a whole big column of water, mixed in with the plant. The cells are very nutritious.”

When they came upon a saguaro that had toppled or lost arms or its top, the counters stopped, recorded in their cellphone apps its size, the direction it had fallen and whether it had arms.

At one point Tuesday, Swann encountered a “leaner,” a saguaro swaying slightly.

“It’s very likely to fall down,” he said. “There are cracks in the soil. Its roots have been severed, snapped off, from when it swung back and forth in the rain.”

Storm also damaged homes

The park wasn’t the only place west of the Tucson Mountains to feel that storm’s impacts. In the Tucson Estates neighborhood south of the park and just east of Kinney, the storm uprooted two posts on the awning of Nancy Finateri’s house and knocked power out to her neighborhood for several hours, she said.

A house lying two down from hers suffered similar carport damage, “had their car torn up,” and had a saguaro leaning against it once the storm was over, she said. A window blew out of the house across the street from hers, and “all of the glass blew into my driveway,” Finateri said.

“I’ve been in Tucson over 50 years, and never in my life living in Tucson have I ever seen a storm like that,” Finateri said. “I looked out my window and I couldn’t see a darned thing. It was like a whiteout, just like a fog, like a blizzard.

“The awning over my carport rolled up like a rock. The storm pulled out two of the posts that held it down. They were embedded in cement, but they were pulled up and landed on my roof.”

“Tree tossed like a tumbleweed”

The collapse of 2,000 saguaros at the Ironwood monument blowdown occurred 11 years ago this month. It was far more dramatic than the latest saguaro collapse, and its origins have been thoroughly documented.

On Sept. 8, 2011, heavy rains soaked the ground across the Waterman Mountain area of the monument, which lies about 50 minutes by car northwest of Tucson and an hour’s drive south of Phoenix.

At mid-afternoon the next day, a storm cell — an air mass that moves up and down in convex-shaped loops — that was ranked as the heaviest in the state at that time suddenly collapsed near Waterman Mountain, Peachey wrote in his unpublished account of the incident. The storm was essentially dumped onto the ground there.

“It’s like you turned a fountain upside down,” he said. “Instead of going up, it comes down, and hits the valley.”

The collapse of 2,000 saguaros at Ironwood National Monument occurred in a blowdown 11 years ago this month. It was far more dramatic than the latest saguaro collapse, and its origins have been thoroughly documented.

The National Weather Service had classified the winds in the Eloy area from where the storm came as “tornadic,” or tornado-like, recalled Peachey.

The fallen saguaros were discovered lying in ring-like formation two days later by two flight instructors flying overhead, Peachey wrote.

Over the next 15 months, Peachey and several colleagues mapped the fallen saguaros, which occupied a 5.7-square-mile area.

Most fallen saguaros stood 15 to 30 feet high and were single-stemmed, just starting to form arms. Most of the really big saguaros seemed to resist the windstorm — “they might lose an arm or be topped but not blown over,” he said. One exception was a huge 40-footer that fell.

They found “lots” of palo verde trees that had been ripped out of bedrock in the area, “with the whole tree tossed like a tumbleweed into the surrounding greasewood flats,” he said.

Also affected were large stands of chain fruit cholla, from which cholla balls “exploded,” he said. When he and other investigators drove dirt roads in the area two days after the blowdown, they had to bring push brooms to sweep the chollas off the road so they didn’t get flat tires.

“We found saguaros on the slopes that had the sharp tips of palo verde branches driven into them. If you were out there walking around you would have been in shrapnel of all kinds — tree branches, bases of ocotillos, parts of palo verdes.”

Haboob triggered another incident

The only other major saguaro blowdown known by scientists to have occurred in the Tucson area knocked down “many hundreds” of the towering cacti more than 40 years ago on south-facing slopes on each of four desert mountains, including Tumamoc Hill, home of the University of Arizona’s Desert Research Laboratory.

That’s how former Desert Research Lab Director Julio Betancourt remembers the event from August 1982.

The trigger was a haboob, a towering wall of blowing dust coming from high winds that develop from collapsing thunderstorms.

“I was then a beginning graduate student and was working late sorting packrat middens (waste piles) from Chaco Canyon in my office in the main building of the Desert Lab. No one else was at the Desert Lab when the haboob happened,” recalled Betancourt, now a scientist emeritus for the U.S. Geological Survey in Reston, Virginia.

“I heard the roar of the wind and the next thing that happened was a pressure change inside and all of the old windows blowing open, scattering papers everywhere. It was like a cyclone had hit Tumamoc Hill.

The collapse of the 2,000 saguaros at the Ironwood monument blowdown occurred 11 years ago this month. It was far more dramatic than the latest saguaro collapse, and its origins have been thoroughly documented.

“I ran around the offices trying to close the windows but it was impossible. I heard a boom and looked out the front window in my office which faced the desert garden and saw that the giant saguaro next to our driveway had crashed over the greenhouse. It all happened so fast, really in just a few minutes.”

The next day, Betancourt and the late Ray Turner, a longtime Tumamoc Hill researcher, started counting fallen saguaros, and found more than 400 on the hill in about two weeks. Enough more were discovered to bring the total count to probably more than 1,000 on nearby “A” Mountain, as well as on Martinez Hill and Black Mountain in the Tohono O’Odham San Xavier District south and southwest of Tucson, respectively.

Six major thunderstorms had blasted Southern Arizona that month, including four that dropped 2 to 4 inches of rain in the Tucson area, with most accompanied by high winds. Most of the fallen saguaros were larger ones, and most were uprooted, not sheared, Betancourt said.

“Extreme precipitation events”

The possible climate change link that UA’s Castro sees with the saguaro blowdowns stems from an analysis of the monsoon’s behavior that he and four other researchers published in 2019.

Their analysis concluded that in both North America and the Amazon River Basin, total monsoon precipitation had fallen over 20 years as climate change, triggered by fossil fuel burning and other greenhouse gases, pushed up temperatures. But at the same time, the frequency of “extreme precipitation events” had increased, they found. Their study was published in the journal Current Climate Change Reports.

Castro is a professor and interim head of UA’s Hydrology and Atmospheric Sciences Department. He said it’s “a reasonable hypothetical” that climate change could be linked to the recent blowdowns.

“We’ve had one of the hottest summers here in Arizona that we’ve ever had. Phoenix has been the hottest it’s ever been, bar none. It’s going to put stress even on our desert vegetation.

“When you would get an intense monsoon storm, those saguaros are going to be weakened anyway and blow down.” he said.

His 2019 study concluded that even though monsoon storms may not be happening as often as they used to, “when they occur in the right conditions, they’re tending to be more intense.”

That pattern described in the study is consistent with what we see worldwide in storm behavior today, he added.

“This summer, we’ve been a series of really spectacular flooding events all over the world — Spain, Greece, Libya, and in China, just to name a few,” he said.

Castro added, however, that “I would have no reason to disagree” with those such as Swann and Peachey who say more data about saguaro blowdowns from a longer period than now exists is needed to document whether climate change is causing them or making them worse.

“There is in no way I’m saying there’s a published paper or scientific process saying that we’ve explicitly proved this. I’m not saying climate change caused it to happen,” Castro said.

“But I’m saying it seems consistent with the pattern that our monsoon is getting more extreme and variable. That will put more stress on our local ecology, including our saguaro plants. If our plants are more stressed, we may be more prone to a blowdown in a big event.”

Photos: Saguaro National Park through the years

Saguaro National Park

Updated

The Saguaro National Monument cactus garden in 1955.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

The Saguaro National Monument visitors center in 1955.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

The Saguaro National Monument visitors center in 1955.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

The Saguaro National Monument visitors center in 1955.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

The Saguaro National Monument West visitors center, left, with two rangers' apartments under construction in 1966.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Saguaro National Monument East unit loop drive in 1958.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Saguaro National Monument East, ca 1950s.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Saguaro National Monument in 1935.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Snow at Saguaro National Park East (then called Saguaro National Monument) on Dec. 23, 1965.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Undated photo (probably 1950s) of tourists enjoying picnics and hiking at Saguaro National Monument.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Saguaro National Monument visitors center ca 1940s.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

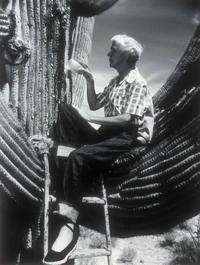

Home Shantz, a plant scientist and president of the University of Arizona in the 1920s, was instrumental in establishing Saguaro National Monument in 1933.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Panorama of cactus forest in Saguaro National Monument, 1931.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Dr. Alice Boyle applies Penicillin to a Saguaro cactus at Saguaro National Monument. Dr. Boyle’s studies of saguaros included treatments with penicillin that were somewhat successful. Later research showed that the loss of old saguaros was a result of age and periodic freezes, not a “blight”!

Saguaro National Park

Updated

The Freeman family in Saguaro National Monument in 1936.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Freeman's adobe home in Saguaro National Monument in 1934.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

A park ranger with visitors on the loop drive in Saguaro National Monument in 1961.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Centennial Saguaro cactus outside the Saguaro National Monument visitors center.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Saguaro National Monument cactus

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Snow storm in Saguaro National Monument in 1937.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

A view looking south from Signal hill at the Tucson Mountain Range in Saguaro National Park, Tucson Mountain District in 2016.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

A view looking east from Saguaro National Park, along Picture Rocks Road in the Tucson Mountain District in August, 2016. In the distance, cloud rise over the Santa Catalina Mountains.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

A Saguaro carcass framed at the Saguaro National Park, West, The Tucson Mountain District (TMD) in 2015.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

A southerly view out the window of a picnic shelter built by the Civilian Conservation Corps in the 1930s that was built with surrounding rock in the Ez-Kim-In-Zin Picnic Area at the Saguaro National Park, West, The Tucson Mountain District (TMD) in 2015.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

A desert tortoise makes its way down Kinney Rd. in the Saguaro National Park West, Wednesday, August 10, 2016, Tucson, Ariz. Kelly Presnell / Arizona Daily Star

Saguaro National Park

Updated

A Saguaro cactus off Golden Gate Rd. holds a top full of flower buds at the Saguaro National Park, West, The Tucson Mountain District (TMD) in 2015.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

A view looking south from Signal hill towards Wasson and Amole Peaks from left in Saguaro National Park, Tucson Mountain District in August, 2016.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Visitors take a look at trail maps on the patio of the Red Hill Visitor Center at the Saguaro National Park, West, The Tucson Mountain District (TMD) in 2015.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Visitors from Denver stroll one of the many trails off Golden Gate Rd. at the Saguaro National Park, West, The Tucson Mountain District (TMD) in 2015.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Panoramic view from Spud Rock, including the city of Tucson, from six images, ranging from southeast at left to northeast at right, near Mica Mountain on the western slopes of the Rincon Mountains in the Saguaro National Park on June 2, 2016.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

A hawk watches from his perch at the Saguaro National Park, West, The Tucson Mountain District (TMD) in 2015.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

A zebra-tailed lizard (Callisaurus draconoides) perches on a rock near the Signal Hill Picnic Area at the Saguaro National Park, West, The Tucson Mountain District (TMD) in 2015.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Panther and Safford Peaks in the Tucson Mountains North of Saguaro National Park, West, The Tucson Mountain District (TMD) in 2015.

Ha:san Bak, Saguaro cactus fruit harvest

Stella Tucker uses the sharp edge of a stem of a Saguaro fruit to slice the husk to get to the sweet meat inside as she harvests the fruit in the Saguaro National Park in 2005.

Ha:san Bak, Saguaro cactus fruit harvest

Stella Tucker uses a kuipaD to harvest saguaro fruit in the Saguaro National Park 2005. During the early summer Tucker camps out in the park to harvest and cook the fruit just as her Tohono O'odham ancestors did. Tucker died in 2019 at age 71.

Ha:san Bak, Saguaro cactus fruit harvest

Bob Martens uses a kuipaD, lengths of Saguaro ribs topped by a small limb of creosote, to knock down ripe Saguaro cactus fruit as he helps Stella Tucker during the Tohono O'Odham harvest at Saguaro National Park in 2005.

Ha:san Bak, Saguaro cactus fruit harvest

Under the early morning sun, Jerry Yellowhair strengthens the joint where a small creosote branch is attached to a length of Saguaro rib to make a kuipaD, used to reach the Saguaro fruit.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

1907: Prominent Tucsonan Levi Manning and his family spent the summer at a get-away log cabin high in the Rincon Mountains.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Manning Camp in the Saguaro National Park East, in 2016.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Some of the pots, pans and iron skillets used by the staff during their stays at Manning Camp in the Saguaro National Park on June 2, 2016.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Next generation ranger Ryan Summers, left, and wilderness ranger Shannon McCloskey look over the camps visitors log shortly after arriving at Manning Camp 8,000 feet above sea level in the Saguaro National Park, on June 2, 2016.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Horse shoes on one of the logs making a wall in the cabin at Manning Camp in the Saguaro National Park on June 2, 2016.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Next generation ranger Ryan Summers splits wood for the evening's fire at Manning Camp in the Saguaro National Park on June 2, 2016.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

The view east over Reef Rock, lower left, from Rincon Mountains near Manning Camp in Saguaro National Park, June 2, 2016

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Wilderness ranger Shannon McCloskey, left, and next generation ranger Ryan Summers prepare to do some upgrades to the facilites at Manning Camp in the Saguaro National Park on June 2, 2016.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Sid Kahla, left, and Thor Peterson get a pannier balanced on Goose while packing seven mules for a resupply of Manning Camp ranger station in 2016.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Saguaro National Park trails supervisor Nick Huck, left, and chief of maintenance Jeremy Curtis split up a box of paper towels, distributing the weight evenly among the panniers while preparing for a pack mule resupply of Manning Camp on April 14, 2016. Seven mules were in the supply train and each mule can carry between 100 and 120 pounds.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Wasson and Amole Peaks at the Saguaro National Park, West, The Tucson Mountain District (TMD) in 2015.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Monsoon clouds gather over the cactus forest in the Saguaro National Park West, Wednesday, August 10, 2016, Tucson, Ariz. Kelly Presnell / Arizona Daily Star

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Saguaro cacti backlit by western sun at the Saguaro National Park, West, The Tucson Mountain District (TMD) in 2015.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

A horizontal sliver of sun catches a stretch of cactus in front of the Rincon Mountains just off the Mica View Trail in Saguaro National Park East, Friday, August 12, 2016, Tucson, Ariz. Kelly Presnell / Arizona Daily Star

Saguaro National Park

Updated

This old stone building was constructed in the 1930's by the Civilian Conservation Corps at the Cam-Boh Picnic Area at Saguaro National Park West.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

In the aftermath of an evening summer storm, lightning arcs through the night skies over the Saguaro National Park West in 2012.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Saguaro National Park trails supervisor Nick Huck, left, and chief of maintenance Jeremy Curtis split up a box of paper towels, distributing the weight evenly among the panniers while preparing for a pack mule resupply of Manning Camp on April 14, 2016. Seven mules were in the supply train and each mule can carry between 100 and 120 pounds.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

A Harris' antelope squirrel, a year-round resident of the Sonoran Desert, comes out of from under a bush for a look-see near the Golden Gate Road at the Tucson Mountain District of the Saguaro National Park in 2010.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

A jack rabbit munches on some greens near the Broadway Trial Head at Saguaro National Park Rincon Mountain District in 2015.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Hikers in Saguaro National Park, like these on the King Canyon Trail in the park's unit west of Tucson, can pay park entrance fees at trailheads using a smartphone.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Loop of connected trails at Saguaro National Park East, made up Shantz, Pink Hill, Loma Verde, Cholla and Cactus Forest trails in 2012.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

From atop an outcropping under the Rincon Mountains, Next Generation Ranger Ryan Summers points out the ancient fault line that shifted and formed the Tucson valley to a group of visitors during a geology tour of Saguaro National Park East on April 26, 2016.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Saguaros stand on a ridge line as massive storm clouds drift in the distance along the Hohokam Road at the Tucson Mountain District of the Saguaro National Park in 2010.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Chief of maintenance Jeremy Curtis gets the strap as tight as possible with the help of trail supervisor Nick Huck while preparing a 70+pound propane tank for a pack mule resupply of Manning Camp in the Saguaro National Park, Rincon District on April 14, 2016.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Saguaro National Park ─ Sunset can be a colorful time along a network of trails near the eastern end of Broadway.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Ranger Donna Gill points out cactus flowers and birds during the Twilight Glow to Moon Shadows hike on the Sendero Esperanza Trail at Saguaro National Park West in April, 2016.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Hedgehog cacti are in brilliant fuchsia bloom at many sites around Tucson from Sabino Canyon to Tucson Mountain Park and Saguaro National Park in 2015.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Russell Jones takes a picture at the Saguaro National Park West Red Hills Visitor Center in 2009.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Poppies were blooming profusely at Saguaro National Park West on February 23, 2015

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Mike Ward of Saguaro National Park, left, and volunteer LaDeana Jeane observe a Saguaro cactus while conducting a census at the east section of Saguaro National Park in 2009.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Gavin Youngstrum drives a roller along the bed of the new Mica Springs Trail, work which will make it ADA compliant in Saguaro National Park East on April 22, 2016, Tucson, Ariz. Power tools and motorized equipment is used very rarely in the park. The trail is not in a wilderness area so the prohibition on the use of power tools and machinery doesn't apply.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

A blue Arizona lupine mixed in with a handful of yellow bladderpod along the Ringtail Trail in Saguaro National Park Tucson Mountain District in 2013.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Park Ranger Ann Gonzalez watches the campers in her group as they go over a map during Junior Ranger Wilderness Day Camp at the Saguaro National Park in 2009.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Petroglyphs are among the many wonders at Saguaro National Park West.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Runners top the first climb as the sun rises at 6:30am, during the annual 8K Saguaro National Park Labor Day Run at Saguaro National Park East in 2007.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

A saguaro under the stars, including a smudge of the Milky Way, at the Broadway Trail Head at Saguaro National Park Rincon Mountain District in 2015.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Sunset reflected in a mud puddle left over from heavy rains a few days earlier at the Broadway Trail Head of the Saguaro National Park Rincon Mountain District in 2015.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

The moon hangs high over Wasson Peak as Ranger Donna Gill leads hikers during the Twilight Glow to Moon Shadows hike on the Sendero Esperanza Trail at Saguaro National Park West in April, 2016.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Volunteers help yank out the nonnative, invasive buffelgrass at Saguaro National Park East.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Using a laser, amateur astronomer Joe Statkevicus points out a few interesting objects in the night sky to Landon George and Vickie Miller at a Saguaro National Park East Star Party in 2010.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

A bee works through a patch of baldderpod in the Saguaro National Park Tucson Mountain District along the Ringtail Trail in 2013.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Trail worker Brad Duffe redistributes material as he and his trail crew lay down a bed for a new surface, part of remodeling the Mica Springs Trail to make it ADA compliant in Saguaro National Park East on April 22, 2016.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Riders maneuver their mounts down a hillside just north of the Douglas Spring Trail in the Saguaro National Park Rincon Mountain District, Friday Nov. 27, 2015.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Tim and Connie Phillips, from Salt Lake City, look for photo angles during the Twilight Glow to Moon Shadows hike on the Sendero Esperanza Trail at Saguaro National Park West in April, 2016. The retired couple sold their home and are "following the weather" across the country in their RV.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

A few items, photos and brief entries in tiny notebooks from an unofficial shrine at Mica Mountain in Saguaro National Park on June 2, 2016.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

The sun sets over the Saguaro National Park Rincon Mountain District on Oct. 8, 2015.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Scarlett Gates and the rest of the tour group watch the last few minutes of daylight from a rock outcropping along the Tanque Verde Ridge Trail during their guided sunset hike in Saguaro National Park East on April 16, 2016.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Gold poppies stand out against a backdrop of cacti and blue desert sky at Saguaro National Park west of Tucson on March 11, 2019.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Rainbows pop up over Saguaro National Park East, as the first major monsoon storm of the season begins to roll into the valley, Tucson, Ariz., July 11, 2020.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

A half rainbow arcs over Saguaro National Park East as a highly localized cell of monsoon rain sweeps through a small band of the eastern valley, Tucson, Ariz., July 28, 2020.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

A light coating of snow remains on the Rincon Mountains seen nearby the Broadway Trailhead in Saguaro National Park in Tucson, Ariz. on January 27, 2021.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

A cactus in the Saguaro National Park East stands in front f the snow in the higher reaches of the Santa Catalinas, Tucson, Ariz., March 13, 2021.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

A lighting strikes hits in the Saguaro National Park, east of Tucson, Ariz., July 29, 2021, one of several storm cells that skirted the city.

Husband-and-wife scientists hand off research after 43 years.