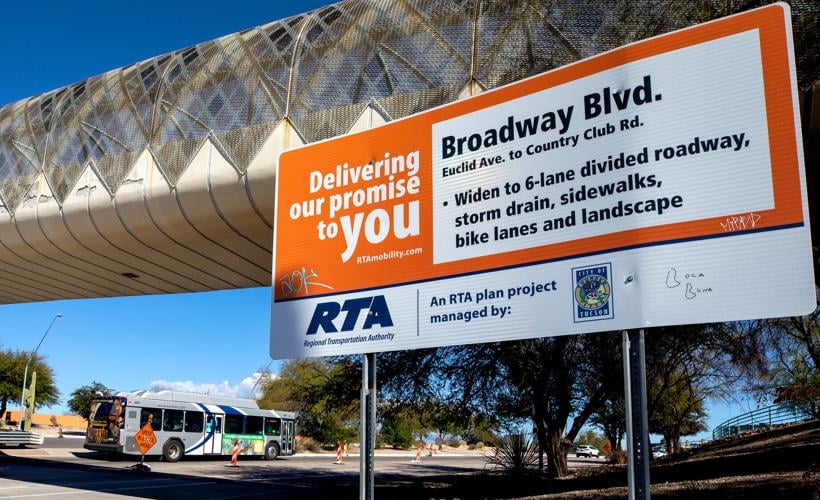

The Regional Transportation Authority has been responsible for hundreds of roadwork projects — ranging from new sidewalks to road expansions — since Pima County voters authorized an RTA sales tax for a two-decade term in 2006.

The program has pumped more than $1.4 billion into the region and is one of the most important sources of transportation funding for communities throughout the county. Now the goal is to keep it alive through a new iteration of the program called RTA Next, which could be on the ballot as early as 2024.

But that plan could live or die depending on what happens Thursday, when officials will have to find a solution to a conflict that could cause the city of Tucson to exit the program — and bring nearly half of the county’s voters with it.

“I think that would be very, very problematic and probably lead to the failure of the RTA at the ballot box,” said Gen. Ted Maxwell, one of nine members of the RTA’s governance board who represents the Arizona Department of Transportation. “I’ll tell you the impact of the RTA not being around is much greater than anybody really realizes or imagined.”

The conflict began last year as city officials faced a massive funding shortfall for Tucson’s current RTA projects, began raising issues about what they called an “inequitable” RTA governing structure and demanded changes to the committee tasked with designing RTA Next.

Tucson’s City Council vowed to withdraw unless RTA leaders take five votes “at the very least” to address the concerns at Thursday’s meeting, though only two such votes have taken place since September.

“They need to make some votes and make some commitments,” Councilman Steve Kozachik said. “We’ve got conversations started, but they’re just conversations, and I think they need to make some actual, real, tangible progress.”

Local officials agree they are unlikely to reach a “tangible” solution in time and are banking on the city to push its deadline back before big changes are made.

A delay is not an option for Tucson. The city has its own upcoming road work initiative, Proposition 101, that will have to be adjusted depending on what happens with the RTA, and it needs to be submitted to election officials by Feb. 1.

Compromise at the RTA also seems unlikely as the city has refused to give any ground, and other members remain opposed to Tucson’s demands, with some like Marana Mayor Ed Honea even suggesting they would leave the RTA if certain changes are made.

“I just don’t think we’re going to crash to the city’s pressure,” said Honea. “We’re standing out in the middle of Broadway, and the city’s driving a Tucson bus down the middle of the road and telling us if we don’t do what they want, they’re going to run over us. Right now we’re kind of saying, ‘well fine.’”

The end of the RTA could spell trouble for the entire region. It would put decades of Tucson road work at risk, stunt the expansion of Arizona’s transportation network and deprive communities of much needed infrastructure they couldn’t afford without outside help.

Weighted voting a long shot

One of the most contentious issues involves tweaking the governing board’s voting structure. It’s a sticking point for Tucson, a no-go for many other members and may be tricky to change even if the board can come to a consensus.

The RTA Board is made up of representatives from eight communities: Tucson, Marana, Oro Valley, Sahuarita, South Tucson, Pima County, the Pascua Yaqui Tribe and the Tohono O’odham Nation. Maxwell from ADOT is the ninth voting member.

Each jurisdiction has one vote despite representing vastly different sized populations, which range from about 6,000 residents to nearly 600,000. The city says the system disenfranchises Tucsonans who have only 11% of the vote despite representing 52% of the region’s population.

Changing that voting structure is not as easy as just getting the board members to agree to a new model, however. Arizona law requires each member to have one vote, so changes at the state-level would have to be made — something officials agree could lead to bad things for the RTA.

“They might go back and look at other rights that have been granted to the RTA, like the ability to go to the voters with additional revenue beyond the existing half-cent,” said Supervisor Rex Scott, who represents Pima County on the RTA board. “That was controversial when the Legislature approved (the RTA) the first time and we just don’t want to reopen that.”

Romero proposed using a separate state law to get around the restrictions by first adding members to the Pima Association of Governments, a regional organization related to the RTA.

State law requires the RTA Board’s membership to mirror that of PAG’s governing body, called the Regional Council. In theory, a change to PAG’s council would automatically be applied to the RTA.

But that adjustment would still need to be approved by the governor’s office, and local officials who oppose the voting changes have said they would actively prevent the approval from happening.

“In order for us to go to any kind of weighted voting at PAG, we have to go to the governor and get it approved,” said Mayor Honea, one of the staunchest opponents of the voting system change. “The governor’s a friend of mine, and I’m going to be up there screaming, so I don’t know if he would do it.”

Other board members rejected Romero’s proposal because it gave Tucson 40% of the total votes, or eight times the voting power of each of the seven smaller jurisdictions.

Sahuarita Mayor Tom Murphy said if the plan were implemented there would be “almost no reason for a lot of us to even show up.” Rex Scott also said he wouldn’t support it even though he would gain votes under Romero’s plan.

“That proposal is never going to be acceptable to everybody on the council, and I’m fairly certain that a political leader with the experience and savvy of Mayor Romero knows that,” Scott said. “The proposal that she presented at the last meeting was not a compromise proposal.”

Scott proposed another plan that would give each PAG member a certain number of votes based on population rather than adding members, something he said doesn’t need outside approval.

The voting power is more balanced in his proposal, but it only applies to PAG and won’t change the RTA’s voting system. The city could still gain some extra influence through certain PAG decisions that can impact grant funding at the RTA, for example.

Other jurisdictions would still have to agree, which will require them to sacrifice their own voting power.

Honea and Murphy aren’t on board with the change. Oro Valley Mayor Joe Winfield said he hasn’t taken a position yet, but he’s often pushed back against the proposals during board meetings.

All three said the change could pave the way for smaller towns to be disenfranchised in RTA Next and that they don’t understand why it’s necessary given that more than 95% of RTA Board and PAG votes have been unanimous since 2006.

“I just don’t see how a different voting structure would put us in a different place than where we are,” Winfield said. “If there’s a funding shortfall, voting doesn’t address that. It doesn’t address that concern. It doesn’t change that.”

RTA staff are expected to present new voting system options at Thursday’s meeting. Farhad Moghimi, the program’s executive director, said that there won’t be any “magic” solutions.

Funding gaps

Tucson’s issues with the RTA largely stem from a funding gap that the city estimates could be as high as $250 million.

City officials mainly blame the gap on inflation that made original 2006 ballot amounts far lower than what’s actually needed to complete the projects. They need to receive an “assurance” that the remaining projects will be fully-funded at Thursday’s meeting to remain in the RTA.

“If we don’t get answers on how we get (the projects) funded, that is cheating the taxpayers of the city of Tucson,” Mayor Romero said. “We need to find answers, and the meeting on Jan. 27 will be pivotal in how the city of Tucson moves forward.”

The city is unlikely to get that guarantee this week. The RTA’s Technical Management Committee, which reviews things like project costs, did not even discuss inflation adjustments at its recent meeting.

RTA officials also contend they have done their part by funding Tucson’s projects at the 2006 ballot amount and that any extra costs are the city’s responsibility.

There was an opportunity to shrink the funding gap by millions ahead of Thursday’s meeting by approving a project adjustment that Tucson requested, but documents show the RTA may have failed to capitalize on it.

The adjustment was proposed for North First Avenue, one of the city’s most dangerous roads. It would have eliminated the project’s $28 million funding gap and ensured there was enough money to make safety improvements.

RTA staffers were assigned to review the suggestion but were not provided a “framework for review nor process for making recommendations” to guide their conversation. They ultimately did not reach a decision.

Board members have suggested rolling Tucson’s remaining projects into RTA Next. If the program begins in 2024 — two years earlier than planned — it would open up new funding options and could allow the projects to be completed on time.

“Tucson would be the biggest winner of an accelerated RTA Next because I believe any one of us would agree that the highest priority is completing those last projects that were at the back end,” said Mayor Murphy. “The city would benefit the most.”

But Tucson can’t take a wait-and-see approach because it has its own deadline. Prop. 101, the city’s own transportation initiative, has collected a separate half-cent sales tax since 2017 and is set to expire later this year unless it’s renewed by voters.

If the city leaves the RTA, it needs to recover those funds through Prop. 101 by raising its sales tax to a full cent. City officials need to figure that out by Feb. 1 if they hope to get the initiative on the ballot in time for May’s election.

“We have to decide what we’re taking back to the voters in May. We will send a very clear message to the RTA if we ask for a half cent or if we ask for a full cent,” Kozachik said. “If it’s a full cent, the message back to the RTA is we got tired of waiting — we’re on our own.”

Area of compromise

The Citizens Advisory Committee could be an area for compromise at Thursday’s meeting, according to multiple board members.

The group is composed of 35 individuals from the region who are tasked with developing the RTA Next plan. They decide everything from what projects are included in RTA Next to the construction schedule.

Tucson already scored some victories during committee discussions last fall when the board unanimously passed new membership guidelines that gave the city 19 committee members, five more than they had in 2006.

The board also approved Romero’s motion to consider demographic and “interest” diversity in the committee. The Tucson mayor proposed the motion, in part, to ensure the approved projects include some of the city’s specific needs like transit upgrades.

“I really think that those agreements that we reached on the structure and direction to be given to the CAC indicates that everybody on the RTA Board wants to move forward together,” Scott said. “It seems to me that the best foundation for further dialogue and compromise moving forward is with the CAC. That’s the future of the RTA.”

RTA staff has since selected potential committee candidates, and the board is expected to confirm the new members on Thursday. Board members said they are open to further compromise as the committee puts RTA Next together.

Photos: A look back at Tucson-area streets

Broadway Road, Williams Addition, 1958

Recently paved and improved Broadway Road in Tucson looking east to Craycroft Road (just beyond the Union 76 gas station at left), where the Broadway pavement ended in 1958. At right, is the natural desert of the Williams Addition, an innovative 160-acre development with only 22 homes on large lots. Developer Lew McGinnis bought all but two of the homes by 1980. It is now Williams Centre.

Interstate 10, 1960

Interstate 10 under construction at St Mary's Road in Tucson, ca. 1960.

Cherry Avenue, 1972

Arizona Stadium is off in the distance looking south along North Cherry Avenue on February 9, 1972. At the time the UA was proposing an addition to its football stadium adding another 10,600 seats to the east side of the structure that would involve permanently closing Cherry Avenue. It was also considering a 3,600-unit parking lot, all of which could cost around $11 million.

Speedway Blvd., 1950

Speedway Blvd. looking east from County Club Road, Tucson, in 1950. The controversial "hump" down the middle of the road separated opposing lanes of traffic. It was removed in 1957.

Court Street, 1900

Court Street in Tucson, c. 1900. City Hall is on the left (with flagpole) and San Augustin church is the peaked roof in distance at the end of the street. The building in the left foreground was used for the first mixed school taught by Miss Wakefield( later Mrs. Fish) and Miss Bolton.

Congress Street, 1933

Congress Street, looking west from 4th Avenue, Tucson, ca. 1933. Hotel Congress is at left. Today, Caffe Luce and One North Fifth Lofts have replaced the shops just beyond the Hotel Congress sign on the corner of 5th Ave. and Congress.

Broadway Road, 1900s

Undated photo looking west on Broadway Road from the Santa Rita Hotel in Tucson. The cross street with man on horseback is Stone Ave. Photo likely from the early 1900s, since the Santa Rita was finished in 1904.

Congress St., 1920

Congress Street in Tucson, looking west from 6th Avenue in 1920.

Park Avenue, 1952

Definitely not a safe place to walk: Park Avenue at the Southern Pacific RR tracks in 1952, looking north into the Lost Barrio in Tucson. Park now crosses under the railroad tracks and links with Euclid Ave.

Electric street cars

Electric street cars replaced horse-drawn street cars in Tucson, 1906.

Toole Ave., 1958

City Laundry Co. of Tucson occupied the historic building at right, at 79 E. Toole Ave., since 1915. Prior to 1915, it was a brewery. It was one the oldest buildings in downtown Tucson. The building at left fronting Council Street was built by City Laundry in 1928 and ultimately became the main plant. Both buildings were demolished in 1958 to make way for a parking lot.

Stone Ave., 1971

Updated

The lights of businesses on Stone Avenue in downtown Tucson, looking south from Ventura Street in July, 1971.

22nd Street, 1962

Traffic tie-ups like this one in June, 1962, happened several times a day on 22nd Street at the Southern Pacific Railroad tracks in Tucson. Most of the motorists in this picture had to wait 10 minutes for the two-train switching operation. An overpass solved the problem in 1965.

Benson Highway, 1972

This stretch of the Benson highway near South Palo Verde Road was bypassed after Interstate 10 was opened in 1969. It was just another string of businesses along the road that struggled to survive on August 14, 1972. The four-mile stretch was once a vital thoroughfare before the interstate system was created.

Church Ave, 1966

Greyhound bus depot, left, was located on the northwest corner of Broadway Boulevard and Church Avenue around February 1966.

Campbell Ave., 1960

Gridlocked traffic on Glenn Street, east of Campbell Avenue as thousands of people attended the opening of the new $2 million Campbell Plaza Shopping Center on April 7, 1960. Originally, the parking facilities was designed to handle 850 vehicles but it was overflowing for the event. The plaza is situated on 18 acres and has 18 tenants.

Interstate 19, 1964

Looking south on the Nogales Interstate Highway (now I-19) at the Ajo Way overpass on July 20, 1964.

Meyer Avenue, 1966

Street scene of South Meyer Avenue looking south from West Congress Street on June 26, 1966. All the buildings were demolished as part of the city's urban renewal project in the 1960s and 70s.

Cortaro Road, 1978

Cortaro General Store on the northwest corner of Cortaro Road and I-10 in December, 1978.

Congress St., 1967

A man crosses East Congress Street at Arizona Avenue as this portion up to Fifth Avenue was falling on hard times with only one small shop still in business on May 3, 1967.

Stone Avenue, 1955

The Stone Avenue widening project between Drachman and Lester streets in April, 1955. A Pioneer Constructors pneumatic roller is used to compact the gravel base for an 80-foot roadway. The four-block project cost $37,500.

US 84A in Tucson, 1954

Westbound SR84A (now I-10) at Congress Street in 1954. In 1948, the Arizona State Highway Department approved the Tucson Controlled Access Highway, a bypass around downtown Tucson. It was named State Route 84A, and connected Benson Highway (US 80) with the Casa Grande Highway (US 84). By 1961, it was reconstructed as Interstate 10.

Grant Road, 1962

The new Grant Road underpass at the Southern Pacific RR in December, 1962, as seen looking west on Grant Road east of the tracks and Interstate 10. The Tucson Gas and Electric generating station (no longer there) is at right.

Grant Road, 1966

Grant Road, looking west at Campbell Ave. in 1966.

Old Nogales Highway, 1966

Old Nogales Highway near Ruby Road in July, 1956.

Oracle Road, 1925

This is a 1925 photo of the All Auto Camp on 2650 N Oracle Rd at Jacinto which featured casitas with the names of a state on the buildings. T

Oracle Road, 1950

This is a 1950 photo of the North Oracle Road bridge where it originally crossed over the Rillito River, west of the current bridge.

Oracle Road, 1979

Area in 1979 along North Oracle Road near the entrance of the Oracle Road Self Storage at 4700 N Oracle Rd near the Rillito River which would now be north of the Tucson Mall. There is no apparent record of the Superior Automatic and Self Service Car Wash.

Oracle Road, 1975

Oracle Road, looking south from Suffolk Drive, in March, 1975. Then, it was a four-lane state highway on Pima County land. It was annexed by Oro Valley more than 30 years later.

36th St., 1956

The Palo Verde Overpass south of Tucson (Southern Pacific RR tracks), looking East on 36th Street, in 1956.

Interstate 10, 1966

Large billboards used to line the area along Interstate 10 (South Freeway) between West 22nd and West Congress Streets on May 5, 1966.

Catalina Highway, 1967

Snow clogs the Catalina Highway to Mt. Lemmon at 5,400 feet elevation on Feb. 18, 1967. Rock slides up ahead kept motorists from going further.

Speedway Blvd., 1968

The new Gil's Chevron Service Station at 203 E Speedway on the northeast corner at North Sixth Avenue was open for business in March 1968. The photo is looking toward the southeast.

Catalina Highway, 1955

The Mt. Lemmon Highway on May 18, 1955.

Tanque Verde Road, 1950s

In this undated photo taken in the late 1950s, the Tanque Verde Bridge over the Pantano Wash was allowing traffic to make its way toward the northeast side of town.

Craycroft and I-10, 1966

The TTT Truck Terminal at Craycroft Road and Benson Highway in Tucson in June, 1966. It's a mile east of the original, built in 1954.

Congress St., 1980

Congress Street in Tucson, looking east from the Chase Bank building at Stone Ave. in August, 1980.

Silverbell Road, 1975

Silverbell Road and Scenic Drive in Marana, looking south-southwest in 1975.

Interstate 10, 1962

Interstate 10 (referred to as the "Tucson freeway" in newspapers at the time) under construction at Speedway Blvd. in the early 1960s. By Summer 1962, completed freeway sections allowed travelers to go from Prince Road to 6th Ave. The non-stop trip to Phoenix as still a few years away.

Alvernon Way, 1982

This is a July 2, 1982 photo of flooding along a Tucson street. Might be North Alvernon Way near Glenn Street.

6th Ave, 1960s

The Tucson Fire Department's Station No. 1 was once on the 100 block of South Sixth Avenue, across the street from the Pueblo Hotel and Apartments in the late 1960s. The fire station had been on the site from as early as 1909 and was next door to the Tucson Stables, which had a livery and sold feed for horses. The historic Santa Rita Hotel rises up behind the fire station. The entire block is now the Tucson Electric Power headquarters.

Ruthrauff Road, 1975

Shown in 1975, owboys drive 250 cattle down a frontage road near Ruthrauff Road in Tucson toward the finish line of "The Last Cattle Drive," a 350-mile journey that began in Willcox. The drive ended at the Nelson Livestock Aucions yard, 455 N. Highway Drive. The cattle was sold with proceeds going to the Muscular Dystrophy Assosciation.

Main Ave., 1969

The newly aligned South Main Ave swerved its way along a barren stretch of landscape on May 9, 1969. Note the Redondo Towers in the background.

Congress St., 1970

Traffic along West Congress Street near the Santa Cruz River moves along on July 24, 1970. City authorities had decided to replace the bridge starting in the fall.