The permitting process for a medical sterilization facility in southeast Tucson anticipated to emit trace amounts of cancer-causing gas has been delayed after the EPA asked Pima County to apply more stringent conditions to the rules the facility would operate under.

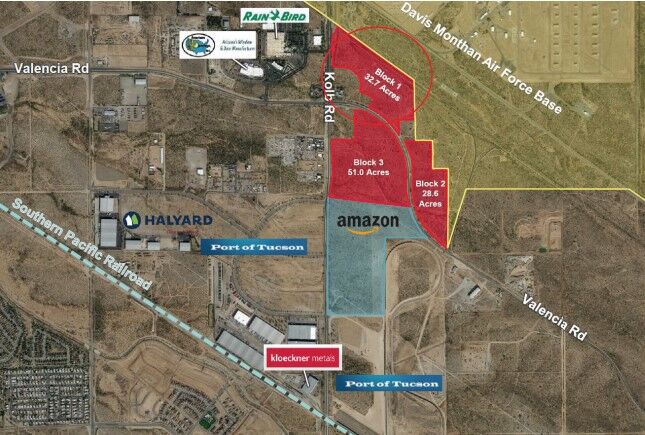

Becton, Dickinson and Co., a multi-billion-dollar medical technology company, plans to begin construction on a 140,000-square-foot facility at 7345 E. Valencia Road near South Kolb Road this year. The facility would use ethylene oxide, a colorless, highly flammable gas that the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency classifies as a human carcinogen, to sterilize medical equipment.

The county’s Department of Environmental Quality, PDEQ, is responsible for monitoring air quality in the region and developing standards for new facilities that emit hazardous air pollutants.

While PDEQ ensures the companies it issues permits to monitor and report pollutants, it doesn’t have much control beyond that. If BD agrees to an air quality permit that meets federal standards set by the Clean Air Act, the country’s primary federal air quality law, the department has to issue it, allowing BD to construct the facility.

The department was previously set to approve BD’s air permit by the end of January but now says the timeline for issuance is delayed for, at most, another two months.

That’s largely because the EPA submitted a list of recommendations to amend the permit to ensure the company controls ethylene oxide emissions while minimizing exposure to the surrounding community.

“Even though we don’t have to, by law, consult with (the EPA), we obviously want to make sure that we are addressing their concerns. We want to make sure we spend the time to review that and incorporate them as best as possible,” said Natalie Shepp, the outreach and education senior program manager for PDEQ. “But it has to be within our authority to do so. How can we make this the most stringent permit we possibly can under the rules that we’re dealing with?”

The concerning nature of the chemical the facility will use has caused both Tucson and Pima County officials to discuss ways to regulate ethylene oxide locally. Discussions have shown there’s not much, if anything, local jurisdictions can do to minimize the facility’s impacts beyond the current federal rules.

“It’s not personality tests, whether I like them or not, or whether I think it’s a good thing or not,” PDEQ’s former Director Ursula Nelson, who retired at the beginning of January, told Tucson’s City Council in December. “If they meet those environmental requirements, then they are allowed to have an operating permit. And that’s what the case is with this facility.”

EPA suggests permit changes

The EPA first classified ethylene oxide as a human carcinogen in 2016, finding the chemical to be capable of changing DNA in a cell, and therefore more dangerous for children whose growing bodies make them more susceptible to harmful effects. The EPA has found evidence that long-term exposure to ethylene oxide increases the risk of myeloma, leukemia and breast cancer.

BD hired an independent consulting company to determine how ethylene oxide emissions at the Tucson site, which neighbors the Davis-Monthan Air Force Base and an Amazon distribution facility, would compare to the EPA’s 100-in-a-million risk threshold level for determining cancer risk if an individual was exposed to a certain concentration of ethylene oxide continuously for a lifetime. The results determined the average levels were five times below the EPA’s risk threshold.

The proposed version of the air quality permit allows the BD facility to emit no more than 709 pounds a year of ethylene oxide into the surrounding environment. According to BD, the facility would have control measures that would get rid of 99.95% of ethylene oxide.

However, the company is facing scrutiny after an Atlanta-based law firm filed more than 150 lawsuits against BD in June 2021 claiming ethylene oxide emissions from its Covington, Georgia, facility since the late 1960s have caused a “cancer cluster among those living or working within a five-mile radius of the plant,” according to a news release from the firm, Penn Law.

BD has denied the allegations and says its ethylene oxide emissions controls, specifically those planned for the Tucson site, exceed federal standards.

When asked for comment on the permitting process for its Tucson facility, the company said in an email, “Out of respect for the process, we won’t comment while the permit is still pending.”

After publishing a proposed permit for the facility, and holding a 90-day public comment period for feedback on it, the county says it’s working on revisions the EPA suggested in December.

The federal agency suggested the county amend the permit to implement a continuous emissions monitoring system, which would measure actual ethylene oxide emissions levels from the facility in real-time. The proposed permit calls for ambient air monitoring, which measures air pollutants in the surrounding area, a process the EPA said “can be difficult to distinguish between pollution from the facility and pollution from other sources.”

The agency recommended the continuous monitoring data be made available to the public to show current ethylene oxide emission rates due to concerns the county has heard “from the community about community access to information confirming that the actual emissions from the facility once built will be as low as the projections from BD that form the basis for the permit limits.”

Rupesh Patel, PDEQ’s air quality program manager, said that technology is “being evaluated for regulatory authority” and that “PDEQ is evaluating the authority with the county attorney’s office related to all elements of the proposed permit.“

While the PDEQ sets the standards for the permit and is responsible for making sure BD follows them, the company will have to implement and obtain the monitoring technology themselves. It’s unclear if BD will be amenable to new, more stringent conditions.

Patel said PDEQ already determined the monitoring conditions in the proposed permit “exceed current federal requirements” necessary for final approval.

The EPA’s letter also told the county to “State that the EPA intends to update the currently applicable standards for commercial ethylene oxide sterilizers.”

The federal agency has been reviewing the regulations for ethylene oxide outlined in the Clean Air Act since 2018. The regulations for commercial sterilizers using ethylene oxide were last updated in 2006, but the EPA plans to announce proposed changes this year. Those could include more stringent regulations for commercial sterilizers but involve many steps that could take years to actually implement.

And when the rules do come into effect, commercial sterilizers would have “no later than three years after the effective date” to comply, Mike Alpern, the EPA Pacific Southwest Region spokesman, said in an email.

“While undertaking the process of putting emissions mandates in place, we are also engaging with communities and our partners on the ground because we know EPA authorities are not the only avenue for achieving emissions reductions and addressing the disparities faced by nearby communities,” Alpern said. “EPA is focusing on early outreach and engagement for regulatory and programmatic efforts.”

But local governing bodies here are finding it difficult to gain any control over an ethylene oxide sterilizer setting roots in Tucson.

County, city lack control

Both Tucson and Pima County officials have expressed concern about the facility’s operations and proximity to vulnerable neighborhoods.

The county Board of Supervisors has discussed the facility twice in the past two months, attempting to navigate the controls it has due to PDEQ’s obligation to issue the permit if it follows federal law.

Those conversations resulted in a motion passed on Jan. 18 to recommend minimum requirements for the final permit, which follow the recommendations provided by the EPA, including implementing a continuous emissions monitoring system and reporting the results “to the maximum extent and frequency allowed under applicable laws and regulations.”

Supervisor Adelita Grijalva said the final motion was amended to make it a recommendation instead of a requirement in consideration of advice from the county attorney’s office.

“What we’re trying to ask is what is the PDEQ’s role versus what we can do, what the city can do?” Grijalva said. “To me, a lot of it is just this process that none of us really have any control over, which is incredibly frustrating, because the pollutants are going here.”

The city is in a similar bind in its discretionary authority for granting land-use permits to the company. The area where BD wants to construct the facility is in city limits and is already zoned for industrial use, leaving the city’s planning and development services department little room to deny the permit.

City Council discussed the facility at a December meeting and asked City Attorney Mike Rankin what controls they have over BD’s operations.

“I don’t see any issue that falls within the review authority of the city. When we’re presented with questions about permits, or applications for permits, we can only base our review, and our issuance or rejection of a permit request based on the criteria over which we have the authority and jurisdiction,” Rankin said. “Which through (planning and development services), or our other departments, doesn’t apply to the issues at hand here.”

And even though the EPA has announced its intent to issue new guidelines for ethylene oxide sterilizers, Rankin told the council, “We can’t delay our development package review based on potential future changes with respect to the federal standards.”

Councilmembers also asked about the Tucson Fire Department’s evaluation of the facility to make sure it follows the city’s fire code.

The Tucson Fire Department has reviewed BD’s operation plans, according to an email Fire Marshal Michael Ashford sent to PDEQ, which said the plans meet the city’s fire code.

“The hazards are in controlled areas and injected in a controlled vessel then extracted thru another system. Under its normal operating conditions, it does not reach airborne concentrations, and also possesses the proper ventilation,” the email said of BD’s plans for the facility. “We (Tucson Fire) is not in a legal position to deny the plans based on our area of concern and what they have presented to us.”

Regardless, Councilman Steve Kozachik is still trying to fight BD’s plans to bring the plant to Tucson.

“I just cannot buy that, setting aside this project, that company X wants to move into the city of Tucson, and they’re bringing a highly toxic chemical that we know is going to be more significantly regulated in the very near future, and we can’t say no?” Kozachik said at December’s meeting. “I just don’t even buy that as a rational response from a governing body.”

Impact to surrounding community

As part of its permitting process, PDEQ conducted an environmental justice report to determine the demographics of the population within 50-square-miles of the proposed facility — an area the department estimates contains 41,760 people.

The results showed the population is comprised of 49% minority communities, 30% low-income individuals and 10% people without a high school diploma — some of the demographics PDEQ considers more “at-risk” when receiving necessary access to information.

But the EPA recommended PDEQ revise this report to show “populations most likely to receive the highest impacts from the project based on the modeled impacts” by breaking down the populations within a three and one-mile radius of the facility. Shepp said the new report, which includes these suggestions, will be available by the end of January.

However, if the results change, the department doesn’t have the authority to amend the permit based on the analysis. The EPA asserts it’s still an essential tool to understand impacts to the surrounding community.

“It is important for communities to have access to clear and honest information about how proposed projects can impact their immediate environment and residents’ health,” Alpern said. “If disproportionate impacts are identified through an EJ analysis, this information can help draw the attention of project proponents and other relevant stakeholders to address the identified impact.”

But drawing attention to possible pollutants’ disproportionate impact on vulnerable communities is not necessarily enough to stop polluters from operating there.

“One of my frustrations with the environmental justice regulations from the Environmental Protection Agency is that we have to do an analysis and we have to do a report, but EPA has not given us any regulatory tools to address the impact of that,” Nelson, PDEQ’s former director, told the City Council. “So we can look at — I’ll call it an overburdened community — and go yes, the environmental justice analysis shows that it’s an overburdened community. But that doesn’t give us the ability to say no to a permit or the ability to require additional reductions.”

Despite a lack of authority, and legal advice City Council has received, Kozachik said he plans to bring the BD facility and possible controls the city can put on it back up at the council’s meeting on Feb. 8.

“We should say no, we should have no part of this,” Kozachik said. “Or 20 years from now, somebody is gonna look back and say: ‘Why did they let that plant go in?’”

Dave Pederson shot this time lapse of the sunset on Dec. 28, 2021, using his iPhone.